Étiquette : Martin de Vos

Pieter Bruegel the Elder, political commentator and pacifist

Five centuries after his birth, the publication of new research seems (finally) to do justice to the great Flemish painter « Pieter Bruegel the Jolly » , known as the Elder (1525-1569).

Until now, it was all too common to hear him described as « an unclassifiable figure. » In 2024, art historian Mónica Ann Walker Vadillo did not hesitate to write in the History section of the newspaper Le Monde that, since Bruegel painted peasant feasts and weddings, art critics « came to regard him as an unrefined man and disdainfully nicknamed him ‘Bruegel the Peasant,' » while expressing surprise that so many « academics, humanists, and wealthy businessmen—who appreciated his work and collected his paintings » associated with him.

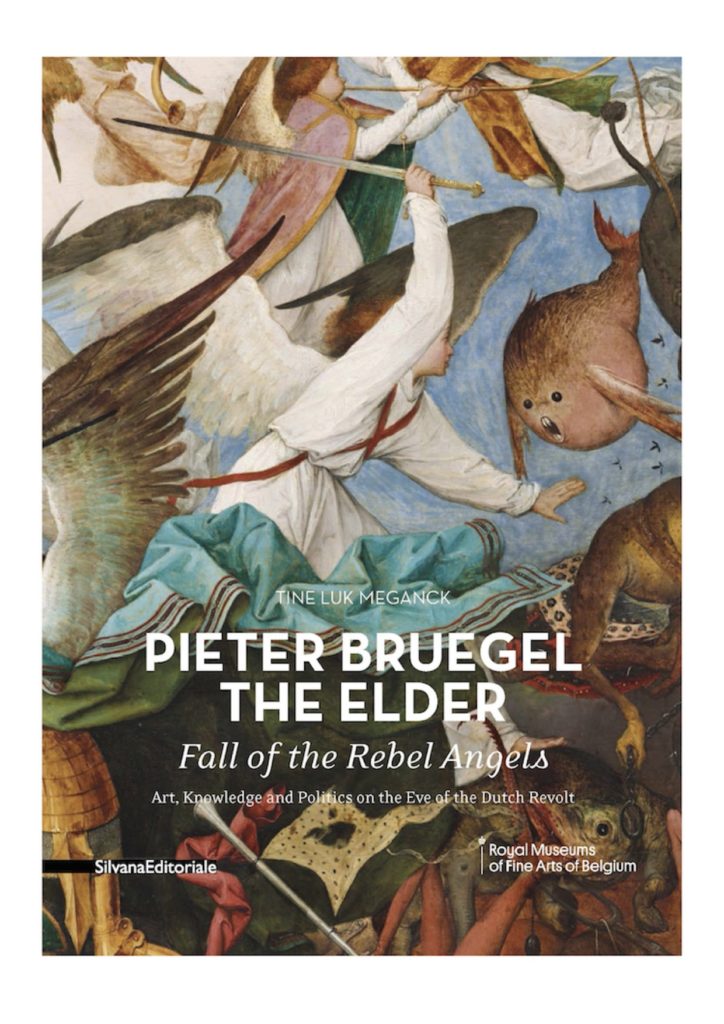

Fall of the Rebel Angels

In 2014, Tine Luk Meganck ‘s book, « Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Fall of the Rebel Angels. Art, knowledge and Politics on the Eve of the Dutch Revolt », especially with the last sentence of her title, had nevertheless reopened the debate on the political dimension of his work.

Meganck ventured a highly improbable hypothesis regarding the painting The Fall of the Rebel Angels (1562, Brussels Museum): the jealous angels, whom God punishes for conspiring against him, are supposed to represent the alliance of nobles, the middle classes, and the common people, led by William the Silent against the rule of the Spanish Empire. Consequently, the commissioner of the work, according to the expert, was most likely the famous Cardinal Antoine Perrenot de Granvelle, one of the advisors to the regent Margaret of Parma and a fervent supporter of the persecution of heretics.

We have documented in an article why this interpretation seems unacceptable to us, as Cardinal Granvelle, a member of the « secret government, » was universally hated by the humanists of the time for his blind zeal in endorsing all the crimes of his masters.

Furthermore, no tangible proof exists that he commissioned any work from Bruegel. Certainly, he owned some, but apart from a « Flight into Egypt » (1563), a work devoid of any controversy, and a « View of the Bay of Naples, » a beautiful study inspired by drawings made during Bruegel’s trip to Italy, Granvelle was far from being « one of the greatest collectors » of Bruegel’s works, as is often repeated.

Landjuweel

That being said, the important contribution of Meganck’s book, let’s acknowledge it, was the recognition of the decisive influence of the Chambers of Rhetoric and the Antwerp Landjuweel of 1561, for understanding Bruegel’s visual language.

My friend, the late American art critic Michael Frances Gibson, had mentioned this possibility to me during an interview this author conducted with him.

He discusses this in his book The Carrying of the Cross (Editions Noêsis, Paris 1996), which was used in 2011 for the quite innovative film « Bruegel, the Mill and the Cross ».

In August 1561, Antwerp, where Bruegel resided, hosted an exceptional celebration, the Landjuweel, or national competition of the Chambers of Rhetoric.

In practice, the Antwerp Chamber « De Violieren« , in charge of organizing a festival that cost the city one hundred thousand crowns, operated as the literary division of the Guild of Saint Luke, the corporation that brought together painters, engravers, illustrators, architects, sculptors, cartographers, goldsmiths and printers.

It was there that people read in Flemish as well as in Latin or French, Plato, Homer, Petrarch, Erasmus and Rabelais, both during private gatherings and often, in public.

The first Bible in French? Printed in Antwerp in 1535 by the French humanist Jacques Lefèvre d’Etaples (1450-1536), who published the first translations of the complete works of Nicholas of Cusa in Paris in 1514, three years before the publication, in the French capital, of the first edition of Erasmus‘s In Praise of Folly.

The Landjuweel of Antwerp stands historically as one of the most remarkable cultural renaissance events in European history. 2000 rhetoricians on horseback, from 10 cities, passed under 40 triumphal arches to the strident sounds of fifes, entering a city in full celebration. For a whole month, orators and poets, songwriters and actors competed without pausing for breath. Citizen’s were invited on every streetcorner to participate in polyphonic madrigals and chorusses. 5000 artists entertained close to a 100,000 viewers !

Bruegel had to follow them all the more since his dear friend Hans Frankaert (1520-1584), his friend and master Peeter Baltens (1527-1584), very well connected with the great local financiers who preferred commerce to war, as well as his first patron, the engraver Hieronymus Cock (1518-1570), were all involved in the organization of this event whose theme was peace and, two centuries before Kant and Schiller, this burning philosophical question: « What leads man most towards the arts? » This, then, was the bubbling cauldron of urban culture in which Bruegel was immersed from his beginnings.

Moreover, as Belgian historian Leen Huet details in her sumptuous biography of the artist (first published in Dutch in 2016 by Polis, then in French by CFC in Brussels in 2021), when he crossed the Alps, Bruegel was probably accompanied by the painter Maarten de Vos (1532-1603) and the cartographer Abraham Ortelius (1527-1598), a close friend of Christophe Plantin, the head of the largest printing house in Antwerp, the team having thousands of addresses of collectors in connection with the printing house Les Quatre Vents of Jérôme Cock, in Antwerp.

The « Bruegel Code »

The image of Bruegel as a political commentator, deliberately obfuscating his message to thwart the regime’s Gestapo agents who were lying in wait for him, and embracing the Erasmian philosophy of the Landjuweel to defend peace and mutual understanding, is further developed by the classical historian Leo Spaepen, whose recent book, Pieter Bruegel de oude, politiek commentator en pacifist. De Bruegel Code (published in Dutch by MER Books, 2025), has stirred enthusiasm.

A good pedagogue, Spaepen establishes a kind of code for deciphering, or at least fruitfully approaching, Bruegel’s visual language. Escaping the Aristotelian confines, the aim is to immediately discard formal and symbolic representations in favor of what I would call a metaphorical approach.

Narrative A and B

Each painting contains a « narrative A » and a « narrative B. » The former typically reflects a concern shared by the humanist and Erasmian community regarding the socio-political events of the time, where corruption and violent Spanish repression brought the Hispano-Burgundian Netherlands to the brink of revolt. The « narrative B » often depicts a scene from the Bible or scripture.

As with any metaphor, the paradox arising from the analogy between narrative A and B brings forth, not on the canvas but in the viewer’s mind, a range of clues allowing them to grasp where the painter intends to lead them.

Spaepen, whose courage, rigor, and audacity deserve high praise, has sufficiently delved into the political and cultural history of Bruegel’s era to formulate compelling hypotheses that illuminate his major works. By testing this cognitive approach, painting by painting, the author generates not a scholarly compendium of facts or evidence, but an extremely interesting « gestalt » of the painter, whose true genius has often been denied recognition. It is therefore impossible, in a simple article like this, to reproduce the full richness of this approach.

« Mad Meg »

Let us nevertheless look at an emblematic work by Bruegel, known by its nickname, Dulle Griet (« Margot the Enraged » or « Mad Meg » ), a work painted in 1563, not to please a patron, but to provoke discussions with his relatives during meals at his home, as was the custom at the time.

The painting is striking in its contradictions. In the foreground, against a backdrop of burning cityscapes, a woman, mad with rage, sword in hand, carries a basket filled with jewels and precious metalwork. Behind her, a cohort of unarmed women bravely strives to subdue and repel an army of monsters and devils.

Finally, at the intersection of the painting’s diagonals, a strange creature appears, reminiscent of Hieronymus Bosch ‘s Garden of Earthly Delights. A man carrying a large bubble on his back shakes his backside, from which silver coins fall, which some women hastily gather up.

As for narrative B, we find roughly the image that Bruegel had developed in a drawing used for a 1557 engraving representing one of the deadly sins, here rage ( Ira in Latin), again represented by a giant woman, with the subtitle: « Rage swells the lips and sours the character. It troubles the mind and blackens the blood. »

Spaepen also picks up on (p. 131) a great find by Leen Huet. The historian discovered that during the Landjuweel of Antwerp in 1561, the chamber of rhetoric of Mechelen had mentioned a « Griete die den roof haelt voor den helle » (a girl who goes to plunder hell), a figure perhaps taken from a play that is now lost.

Huet also mentions (p. 35) the Flemish proverb that says of an old harpy that she « could go and plunder hell and come back safe and sound. » At the same time, Huet notes (p. 48), the author Sartorius , in a collection of adages inspired by Erasmus, states a saying similar in spirit to the Dulle Griet sign:

« One woman alone makes a racket, two women cause much trouble, three women gather only to trade for an annual market, four women lead to strife, five women form an army, and against six women, Satan himself has no weapon to fight them. »

In reality, the status of urban women from the 15th century onwards in Flanders, with the beguinages, and especially in Brabant in the 16th century, was one of the most advanced in Europe1, probably explaining in part the concerns of some members of the male gender in the face of the growing power of women.

Granvelle

But Spaepen, a good observer, exonerates Bruegel from this kind of masculinist reaction by bringing back the reality of narrative A, the current political situation.

The painter, Spaepen believes, is denouncing here Cardinal Granvelle , zealous advisor to the regent Margaret of Parma, a woman torn between the general interest and submission to the tyranny of the Catholic Church, whose dogmas were instrumentalized by Madrid to plunder the country in order to repay the colossal debt of Charles V and Philip II to the Fugger bankers.

Personally, I thought for a moment that Bruegel had invented for the occasion an 8th deadly sin, « incitement to war » (Oorlogstokerij), but I am probably too much in the present.

In August 1561, disregarding Granvelle’s advice, Margaret had authorized the Guild of Saint Luke and the Violieren to organize the Antwerp Landjuweel to promote peace and mutual understanding. But immediately afterward, she yielded to pressure from Madrid by forbidding the publication of the proceedings of the Chambers of Rhetoric, which were accused of having united the entire country against the Emperor.

In 1563, the year Bruegel painted his Dulle Griet, the Council of Trent decided to curb polyphonic art by restoring the primacy of the sung text in music and prohibiting any ambiguity in a painting, linked to a role of propaganda, exactly as Granvelle wished.

In the painting « Mad Meg, » the strange creature in the center, draped in a red cloak, could very well be Cardinal Granvelle himself.

As Spaepen reminds us, Granvelle had just established a vast network of informants to hunt down heretics « even in the toilets. »

This targeted all those—Lutherans, Calvinists, Erasmians, or Anabaptists—who challenged the predatory grip of the regime. And yet, the money « shat out » by Granvelle is being recovered by women ready to plunder hell! Bruegel, not exactly kind to Mad Meg (Marguerite of Parma), could therefore be expressing his horror at this regent who has lost her mind, and especially at the idea that Flemish women, who had become so free and educated, could end up as informers for a totalitarian regime!

Familia Caritatis

Spaepen (p. 194) documents the strong influence exerted on Bruegel (who was not necessarily a member of the group) by the Familia Caritatis (Family of Charity), a philosophical and religious movement founded and led by Hendrik Niclaes (1502-1570), a prophetic and charismatic figure advocating peace and tolerance about whom little is known but who undoubtedly appeared to many, without reaching his wisdom and erudition, as a kind of successor to Erasmus.

Many humanists and a number of Bruegel’s acquaintances were in contact with this movement which, passing through England, would dissolve into the Quaker revolt against the Anglican Church.2

Plantin, considered the official printer of the Spanish regime, had the Familia Caritatis booklets (deemed heretical by the regime) printed (at night), with initial financial assistance for his printing press from Niclaes, himself a merchant. Niclaes’s major work, Terra Pacis, denounces the « Blind leading the Blind, » a theme also found in the work of Quinten Matsys‘s son (who fled the persecution), and later in Bruegel.

Niclaes draws upon Socrates and the philosophy of the Brethren of the Common Life , for whom selfless love (agape or caritas) should be the driving force of humankind. Another conviction he holds is that life is « a pilgrimage of the soul. »

As in the landscapes of Joachim Patinir, Homo Viator must constantly detach himself from earthly matters and move on. Through his free he must seek union with God by resisting earthly temptations. Inner peace—with oneself, with one’s conscience, and with the divine will—is the foundation of peace on Earth, an ideal that also clearly inspired the painter.

This is the true story, that of a great political commentator and resistance fighter of his time, a painter intellectually and spiritually committed to peace.

NOTES:

- See on this subject Myriam Greilsammer, L’envers du tableau : Mariage et maternité en Flandre médiévale , Armand Colin, 1990, as well as this author’s article on the Landjuweel. ↩︎

- These included the printers Christoffel Plantin and John Gailliart; the humanists Abraham Ortelius, Justus Lipsius, Andreas Masius, Goropius Becanus, and Benito Arias Montano; the poets Peeter Heyns, Jan van der Noot, Lucas d’Heere, Filips Galle, and Joris Hoefnagel; the theologian Hubert Duifhuis; the writer Dirck Volkertsz; Coornhert (right-hand man of William the Silent); the « familists » Daniel van Bombergen, Emanuel van Meteren, and Johan Radermacher; and the Antwerp merchants Marcus Perez and Ferdinando Ximines. ↩︎