Étiquette : Black Plague

Devotio Moderna, Brothers of the Common Life: the cradle of humanism in the North

Presentation of Karel Vereycken, founder of Agora Erasmus, at a meeting with friends in the Netherlands on September 10, 2011.

The current financial system is bankrupt and will collapse in the coming days, weeks, months or years if nothing is done to end the paradigm of financial globalization, monetarism and free trade.

To exit this crisis implies organizing a break-up of the banks according to principles of the Glass-Steagall Act, an indispensable lever to recreate a true credit system in opposition to the current monetarist system. The objective is to guarantee real investments generating physical and human wealth, thanks to large infrastructure projects and highly qualified and well-paid jobs.

Can this be done? Yes, we can! However, the true challenge is neither economic, nor political, but cultural and educational: how to lay the foundations of a new Renaissance, how to effect a civilizational shift away from green and Malthusian pessimism towards a culture that sets itself the sacred mission of fully developing the creative powers of each individual, whether here, in Africa, or elsewhere.

Is there a historical precedent? Yes, and especially here, from where I am speaking to you this morning (Naarden, Netherlands) with a certain emotion. It probably overwhelms me because I have a rather well informed and precise sense of the role that several key individuals from the region where we are gathered this morning have played and how, in the fourteenth century, they made Deventer, Zwolle and Windesheim an intellectual hotbed and the cradle of the Renaissance of the North which inspired so many worldwide.

Let me summarize for you the history of this movement of lay clerics and teachers: the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, a movement that nurished our beloved Erasmus of Rotterdam, the humanist giant from whom we borrowed the name to create our political movement in Belgium.

As very often, it all begins with an individual decision of someone to overcome his shortcomings and give up those « little compromises » that end up making most of us slaves. In doing so, this individual quickly appears as a « natural » leader. Do you want to become a leader? Start by cleaning up your own mess before giving lessons to others!

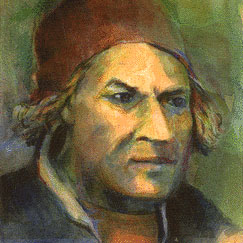

Geert Groote, the founder

The spiritual father of the Brothers is Geert Groote, born in 1340 and son of a wealthy textile merchant in Deventer, which at that time, like Zwolle, Kampen and Roermond, were prosperous cities of the Hanseatic League.

In 1345, as a result of the international financial crash, the Black Death spread throughout Europe and arrived in the Netherlands around 1449-50. Between a third and a half of the population died and, according to some sources, Groote lost both parents. He abhorred the hypocrisy of the hordes of flagellants who invaded the streets and later advocated a less conspicuous, more interior spirituality.

Groote had talent for intellectual matters and was soon sent to study in Paris. In 1358, at the age of eighteen, he obtained the title of Master of Arts, even though the statutes of the University stipulated that the minimum age required was twenty-one.

He stayed eight years in Paris where he taught, while making a few excursions to Cologne and Prague. During this time, he assimilated all that could be known about philosophy, theology, medicine, canon law and astronomy. He also learned Latin, Greek and Hebrew and was considered one of the greatest scholars of the time.

Around 1362 he became canon of Aachen Cathedral and in 1371 of that of Utrecht. At the age of 27, he was sent as a diplomat to Cologne and to the Court of Avignon to settle the dispute between the city of Deventer and the bishop of Utrecht with Pope Urban V. In principle, he could have met the Italian humanist Petrarch who was there at that time.

Full of knowledge and success, Groote got a big head. His best friends, conscious of his talents, kindly suggested him to detach himself from his obsession with « Earthly Paradise ». The first one was his friend Guillaume de Salvarvilla, the choirmaster of Notre-Dame of Paris. The second was Henri Eger of Kalkar (1328-1408) with whom Groote shared the benches of the Sorbonne.

In 1374, Groote got seriously ill. However, the priest of Deventer refused to administer the last sacraments to him as long as he refused to burn some of the books in his possession. Fearing for his life (after death), he decided to burn his collection of books on black magic. Finally, he felt better and healed. He also gave up living in comfort and lucre through fictitious jobs that allowed him to get rich without working too hard.

After this radical conversion, Groote decides to selfperfect. In his Conclusions and Resolutions he wrote:

« It is to the glory, honor and service of God that I propose to order my life and the salvation of my soul. (…) In the first place, not to desire any other benefit and not to put my hope and expectation from now on in any temporal profit. The more goods I have, the more I will probably want more. For according to the primitive Church, you cannot have several benefits. Of all the sciences of the Gentiles, the moral sciences are the least detestable: many of them are often useful and profitable both for oneself and for teaching others. The wisest, like Socrates and Plato, brought all philosophy back to ethics. And if they spoke of high things, they transmitted them (according to St. Augustine and my own experience) by moralizing them lightly and figuratively, so that morality always shines through in knowledge… ».

Groote then undertakes a spiritual retreat at the Carthusian monastery of Monnikshuizen near Arnhem where he devotes himself to prayer and study.

However, after a three-year stay in isolation, the prior, his Parisian friend Eger of Kalkar, told him to go out and teach :

« Instead of remaining cloistered here, you will be able to do greater good by going out into the world to preach, an activity for which God has given you a great talent. »

Ruusbroec, the inspirer

Groote accepted the challenge. However, before taking action, he decided to make a last trip to Paris in 1378 to obtain the books he needed.

According to Pomerius, prior of Groenendael between 1431 and 1432, he undertook this trip with his friend from Zwolle, the teacher Joan Cele (around 1350-1417), the historical founder of the excellent Dutch public education system, the Latin School.

On their way to Paris, they visit Jan van Ruusbroec (1293-1381), a Flemish “mystic” who lived in the Groenendael Priory on the edge of the Soignes Forest near Brussels.

Groote, still living in fear of God and the authorities, initially tries to make « more acceptable » some of the old sage’s writings while recognizing Ruusbroec as closer to the Lord than he is. In a letter to the community of Groenendael, he requested the prayer of the prior:

« I would like to recommend myself to the prayer of your provost and prior. For the time of eternity, I would like to be ‘the prior’s stepladder’, as long as my soul is united to him in love and respect.” (Note 1)

Back in Deventer, Groote concentrated on study and preaching. First he presented himself to the bishop to be ordained a deacon. In this function, he obtained the right to preach in the entire bishopric of Utrecht (basically the whole part of today’s Netherlands north of the great rivers, except for the area around Groningen).

First he preached in Deventer, then in Zwolle, Kampen, Zutphen and later in Amsterdam, Haarlem, Gouda and Delft. His success is so great that jealousy is felt in the church. Moreover, with the chaos caused by the great schism (1378 to 1417) installing two popes at the head of the church, the believers are looking for a new generation of leaders.

As early as 1374, Groote offered part of his parents’ house to accommodate a group of pious women. Endowed with a by-law, the first house of sisters was born in Deventer. He named them « Sisters of the Common Life », a concept developed in several works of Ruusbroec, notably in the final paragraph Of the Shining Stone (Van den blinckende Steen)

« The man who is sent from this height to the world below, is full of truth, and rich in all virtues. And he does not seek his own, but the honor of the one who sent him. And that is why he is upright and truthful in all things. And he has a rich and benevolent foundation grounded in the riches of God. And so he must always convey the spirit of God to those who need it; for the living fountain of the Holy Spirit is not a wealth that can be wasted. And he is a willing instrument of God with whom the Lord works as He wills, and how He wills. And it is not for sale, but leaves the honor to God. And for this reason he remains ready to do whatever God commands; and to do and tolerate with strength whatever God entrusts to him. And so he has a common life; for to him seeing [via contemplativa] and working [via activa] are equal, for in both things he is perfect.”

Radewijns, the organizer

Following one of his first sermons, Groote recruited Florens Radewijns (1350-1400). Born in Utrecht, the latter received his training in Prague where, also at the early age of 18, he was awarded the title of Magister Artium.

Groote then sent him to the German city of Worms to be consecrated priest there. In 1380 Groote moved with about ten pupils to the house of Radewijns in Deventer; it would later be known as the « Sir Florens House” (Heer Florenshuis), the first house of the Brothers and above all its base of operation?

When Groote died of the plague in 1384, Radewijns decided to expand the movement which became the Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life. Soon it will be branded the Devotio Moderna (Modern Devotion).

Books and beguinages

A number of parallels can be drawn with the phenomenon of the Beguines which flourished from the 13th century onward. (Note 2)

The first beguines were independent women, living alone (without a man or a rule), animated by a deep spirituality and daring to venture into the enormous adventure of a personal relationship with God. (Note 3)

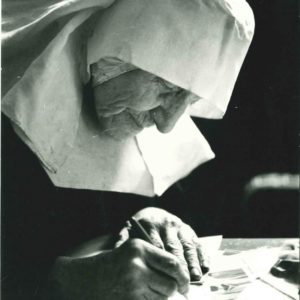

Operating outside the official religious hierarchy, they didn’t beg but worked various jobs to earn their daily bread. The same goes for the Brothers of the Common Life, except that for them, books were at the center of all activities. Thus, apart from teaching, the copying and production of books represented a major source of income while allowing spreading the word to the many.

Lay Brothers and Sisters focused on education and their priests on preaching. Thanks to the scriptorium and printing houses, their literature and music will spread everywhere.

Windesheim

To protect the movement from unfair attacks and criticism, Radewijns founded a congregation of canons regular obeying the Augustinian rule.

In Windesheim, between Zwolle and Deventer, on land belonging to Berthold ten Hove, one of the members, a first cloister is erected. A second one, for women this time, is built in Diepenveen near Arnhem. The construction of Windesheim took several years and a group of brothers lived temporarily on the building site, in huts.

In 1399 Johannes van Kempen, who had stayed at Groote’s house in Deventer, became the first prior of the cloister of Mont Saint-Agnès near Zwolle and gave the movement new momentum. From Zwolle, Deventer and Windesheim, the new recruits spread all over the Netherlands and Northern Europe to found new branches of the movement.

In 1412, the congregation had 16 cloisters and their number reached 97 in 1500: 84 priories for men and 13 for women. To this must be added a large number of cloisters for canonesses which, although not formally associated with the Windesheim Congregation, were run by rectors trained by them.

Windesheim was not recognized by the Bishop of Utrecht until 1423 and in Belgium, Groenendael, associated with the Red Cloister and Korsendonc, wanted to be part of it as early as 1402.

Thomas a Kempis, Cusanus and Erasmus

Johannes van Kempen was the brother of the famous Thomas a Kempis (1379-1471). The latter, trained in Windesheim, animated the cloister of Mont Saint-Agnès near Zwolle and was one of the towering figures of the movement for seventy years. In addition to a biography he wrote of Groote and his account of the movement, his Imitatione Christi (The Imitation of Christ) became the most widely read work in history after the Bible.

Both Rudolf Agricola (1444-1485) and Alexander Hegius (1433-1498), two of Erasmus’ tutors during his training in Deventer, were direct pupils of Thomas a Kempis. The Latin School of Deventer, of which Hegius was rector, was the first school in Northern Europe to teach the ancient Greek language to children.

While no formal prove exists, it is tempting to believe that Cusanus (1401-1464), who protected Agricola and, in his last will, via his Bursa Cusanus, offered a scholarship for the training of orphans and poor students of the Brothers of the Common Life in Deventer, was also trained by this humanist network.

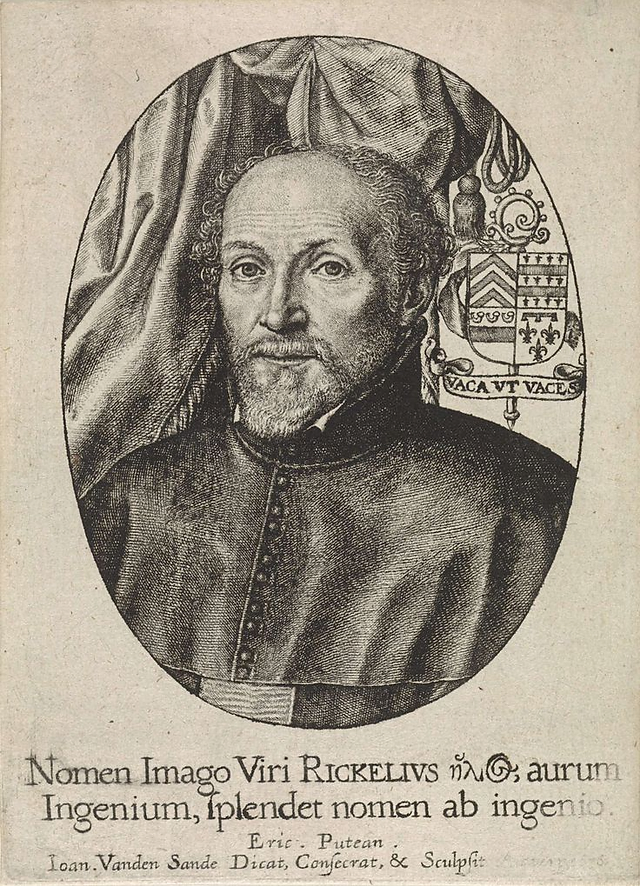

What is known is that when Cusanus came in 1451 to the Netherlands to put the affairs of the Church in order, he traveled with his friend Denis the Carthusian (van Rijkel) (1402-1471), a disciple of Ruusbroec, whom he commissioned to carry on this task.

A native of Limburg, trained at the famous Cele school in Zwolle, Dionysius the Carthusian also became the confessor of the Duke of Burgundy and is thought to be the “theological advisor” of the Duke’s ambassador and court painter, Jan Van Eyck. (Note 4)

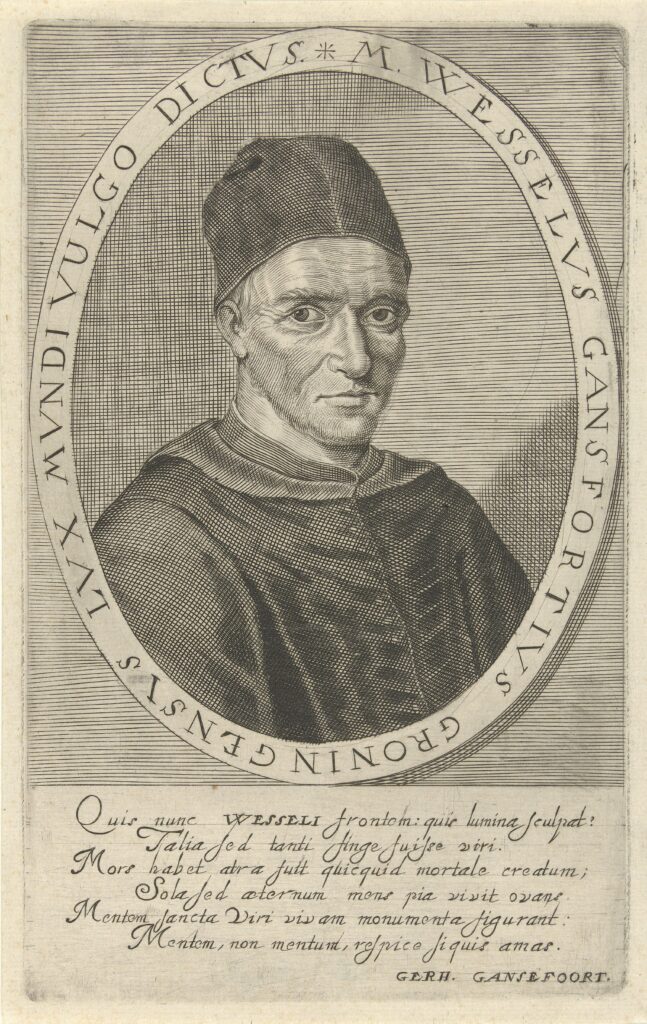

Gansfort

Wessel Gansfort (1419-1489), another exceptional figure of this movement was at the service of the Greek Cardinal Bessarion, the main collaborator of Nicolas of Cusa (Cusanus) at the Council of Ferrara-Florence of 1437. Gansfort, after attending the Brothers’ school in Groningen, was also trained by Joan Cele‘s Latin school in Zwolle.

The same goes for the first and only Dutch pope, Adrianus VI, who was trained in the same school before completing his training with Hegius in Deventer. This pope was very open to Erasmus’ reformist ideas… before arriving in Rome.

Hegius, in a letter to Gansfort, which he calls Lux Mundi (Light of the World), wrote:

« I send you, most honorable lord, the homilies of John Chrysostom. I hope that you will enjoy reading them, since the golden words have always been more pleasing to you than the pieces of this metal. As you know, I went to the library of Cusanus. There I found some books that I didn’t know existed (…) Farewell, and if I can do you a favor, let me know and consider it done.”

Rembrandt

A quick look on Rembrandt’s intellectual training indicates that he too was a late product of this educational epic. In 1609, Rembrandt, barely three years old, entered elementary school where, like other boys and girls of his generation, he learned to read, write and… draw.

The school opened at 6 in the morning, at 7 in the winter, and closes at 7 in the evening. Classes begin with prayer, reading and discussion of a passage from the Bible followed by the singing of psalms. Here Rembrandt acquired an elegant writing style and much more than a rudimentary knowledge of the Gospels.

The Netherlands wanted to survive. Its leaders take advantage of the twelve-year truce (1608-1618) to fulfill their commitment to the public interest.

In doing so, the Netherlands at the beginning of the XVIIth century became the first country in the world where everyone had the chance to learn to read, write, calculate, sing and draw.

This universal educational system, no matter what its shortcomings, available to both rich and poor, boys and girls alike, stands as the secret behind the Dutch « Golden Century ». This high level of education also created those generations of active Dutch emigrants a century later in the American Revolution.

While others started secondary school at the age of twelve, Rembrandt entered the Leyden Latin School at the age of 7. There, the students, apart from rhetoric, logic and calligraphy, learn not only Greek and Latin, but also foreign languages such as English, French, Spanish or Portuguese. Then, in 1620, at the age of 14, with no laws restricting young talents, Rembrandt enrolled in University. The subject he chose was not Theology, Law, Science or Medicine, but… Literature.

Did he want to add to his knowledge of Latin the mastery of Greek or Hebrew philology, or possibly Chaldean, Coptic or Arabic? After all, Arabic/Latin dictionaries were already being published in Leiden at a time the city was becoming a major printing center in the world.

Thus, one realizes that the Netherlands and Belgium, first with Ruusbroec and Groote and later with Erasmus and Rembrandt, made an essential contribution in the not so distant past to the kind of humanism that can raise today humanity to its true dignity.

Hence, failing to extend our influence here, clearly seems to me something in the realm of the impossible.

Footnotes:

- Geert Groote, who discovered Ruusbroec’s work during his spiritual retreat at the Carthusian monastery of Monnikshuizen, near Arnhem, has translated at least three of his works into Latin. He sent The Book of the Spiritual Tabernacle to the Cistercian Cloister of Altencamp and his friends in Amsterdam. The Spiritual Marriage of Ruusbroec being under attack, Groote personally defends it. Thus, thanks to his authority, Ruusbroec’s works are copied in number and carefully preserved. Ruusbroec’s teaching became popularized by the writings of the Modern Devotion and especially by the Imitation of Christ.

- At the beginning of the 13th century the Beguines were accused of heresy and persecuted, except… in the Burgundian Netherlands. In Flanders, they are cleared and obtain official status. In reality, they benefit from the protection of two important women: Jeanne and Margaret of Constantinople, Countess of Flanders. They organized the foundation of the Beguinages of Louvain (1232), Gent (1234), Antwerp (1234), Kortrijk (1238), Ypres (1240), Lille (1240), Zoutleeuw (1240), Bruges (1243), Douai (1245), Geraardsbergen (1245), Hasselt (1245), Diest (1253), Mechelen (1258) and in 1271 it was Jan I, Count of Flanders, in person, who deposited the statutes of the great Beguinage of Brussels. In 1321, the Pope estimated the number of Beguines at 200,000.

- The platonic poetry of the Beguine, Hadewijch of Antwerp (XIIIth Century) has a decisive influence on Jan van Ruusbroec.

- It is significant that the first book printed in Flanders in 1473, by Erasmus’ friend and printer Dirk Martens, is precisely a work of Denis the Carthusian.

The splendors of the kingdoms of Ife and Benin

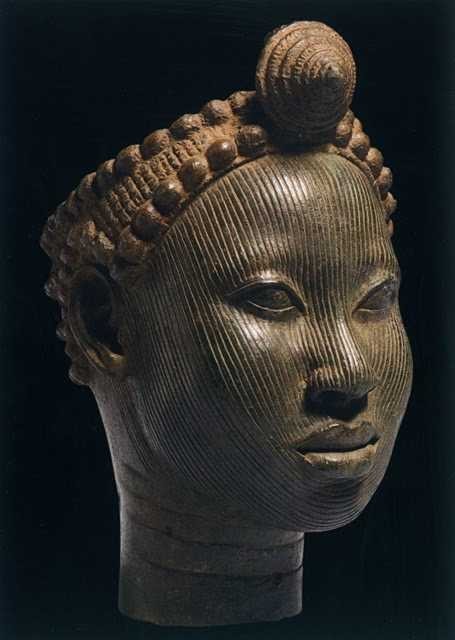

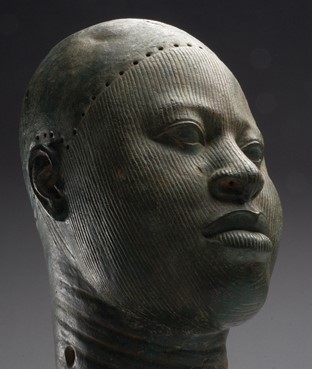

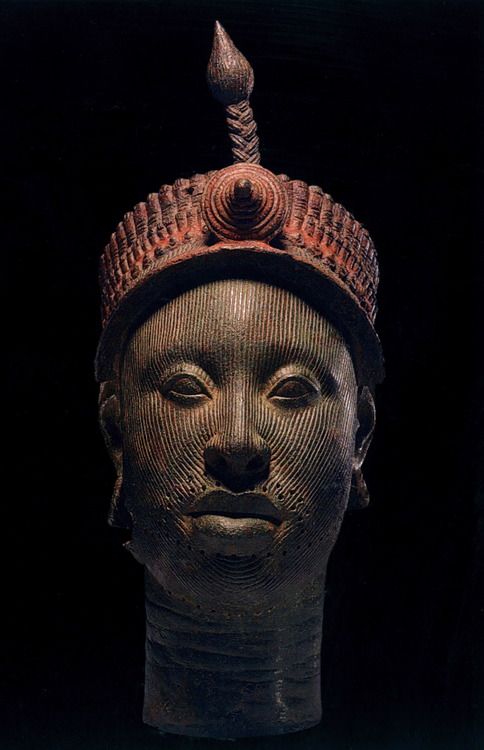

The breathtaking beauty of the XIIth century bronze heads of Ife (Nigeria) challenge the colonial view that Africa was a virgin continent, populated by animals and a few primitive tribes which failed walking their first steps into « history ».

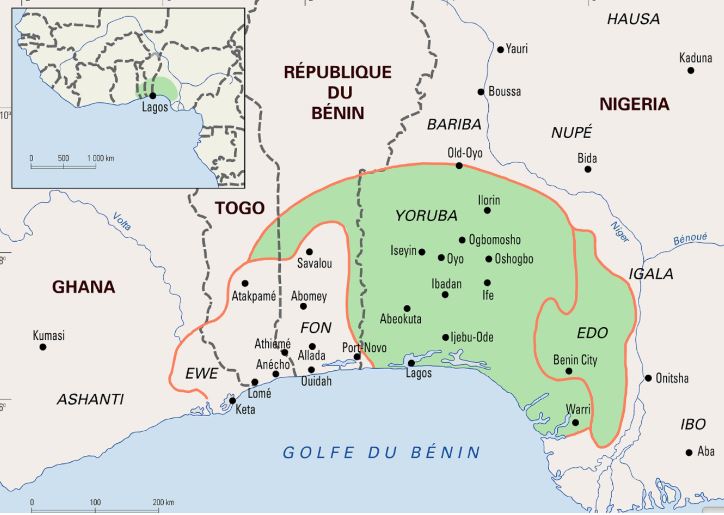

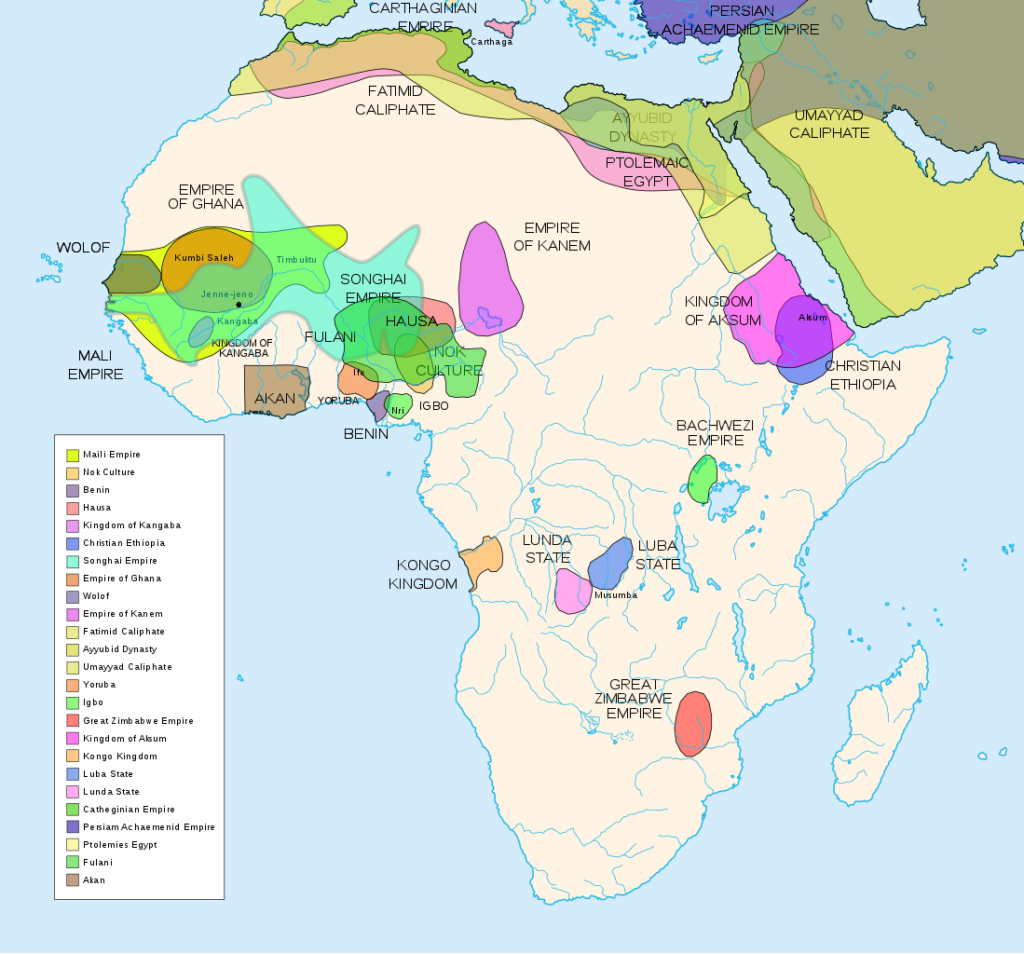

Today inhabited by a half million people, the city of Ife in southwest Nigeria, was formerly the religious center and former capital of the Yoruba people whose prosperity was essentially the fruit of their trade with the peoples of West Africa along the 4200 km long Niger River and beyond.

What some call today “Yorubu-land”, inhabited by some 55 million people, covered some 142,000 km2 comprising vast parts of countries such as today’s Nigeria (76%), Benin (18.9%) and Togo (6.5%).

Today, the Yoruba people live in Ghana, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and, since the slave trade, in the United States. It is not surprising, therefore, that yoruba, also the name of one of the three major languages of Nigeria, is also spoken in parts of Benin and Togo, as well as in the West Indies and Latin America, including Cuba and other settlements populated by descendants of African slaves.

An extraordinary discovery

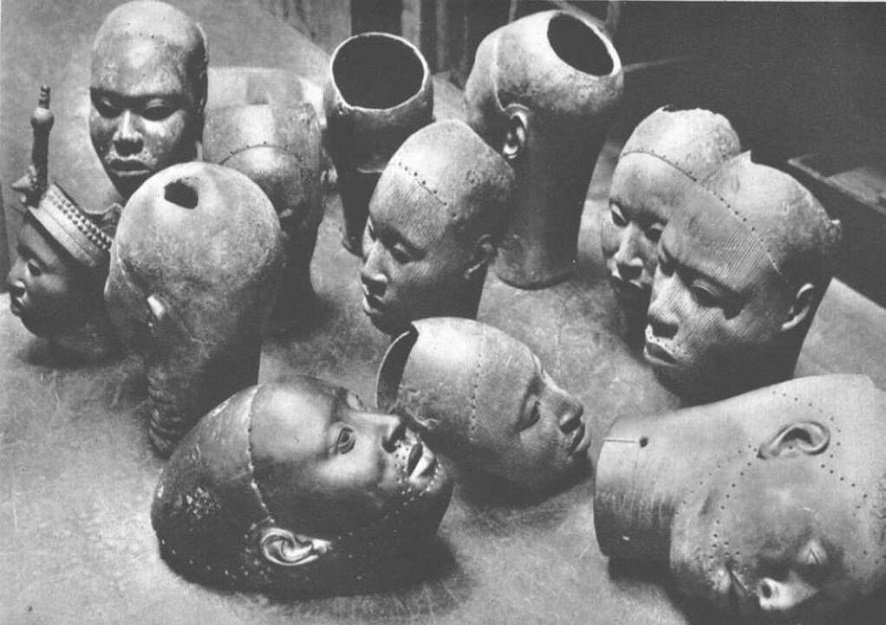

It was in January 1938, during excavation work for the construction of a house, that workers discovered an unusual treasure in the Wunmonije district of Ife. At a mere hundred meters distance away of the site of what once was the Royal Palace, they unearthed thirteen magnificent bronze heads dating from the XIIth century representing a king (an « Ooni« ), some women and courtiers. Others have since been unearthed.

Their faces, except for the lips, are covered with grooves. The hairstyle suggests a complex crown composed of several layers of tubular balls, topped by a crest with a rosette and an « egret ». The surface of this crown bears traces of red and black paint.

These large heads may have been used as effigies of the deceased in funeral ceremonies, which, among the Yoruba, sometimes took place a year after the rapid burial of the dead imposed by the tropical climate.

At the time of the discovery, the extremely naturalist rendering of the heads is considered anachronistic in the art of sub-Saharan Africa, and even more disturbing than the very “classical” i.e. realistic “mummy portraits” (Ist-IInd century) discovered as early as 1887 in the Faiyum depression of Egypt.

Yet a long tradition of figurative sculpture with similar characteristics as the bronze heads of Ife existed before, particularly among the Nok, a people of farmers who mastered iron metallurgy starting from 800 BC.

Hysteria

Since 1938, the « heads of Ife » have provoked reactions close to hysteria in Europe and the West in general.

On the one hand, the « modernists » and the « abstract » artists of the early XXth century, for whom the more abstract a sculpture is and the more distant it is from reality, the more it was considered as typically African. For those who were inspired by African « abstract » art to free themselves from what they considered as materialistic naturalism, the heads of Ife brutally challenged their self-deceiving “smart” narrative.

On the other hand, especially for the supporters of colonial imperialism, this art simply could not be. Frank Willett, at one point the head of the Nigerian Department of Antiquities and author of Ife, an African civilization (Editions Tallandier, 1967), reported that « Europeans visiting Ife frequently wonder how people living in houses of dried mud, with straw roofs, could have made such beautiful objects as the bronzes and terracotta in the museum ». Trying to answer that question, the publisher Sir Mortimer Wheeler replied: “The prejudice is alive and well that artistic creation and sensitivity cannot exist without domestic talent and sanitary comfort!”

The questions of the Europeans were numerous. How, in the XIIth century, could primitive peoples, who had never known an organized form of state, have made bronze heads of such refinement, using techniques that even Europe failed to master at that juncture? How could it have been possible, for tribes, subjected to superstition and irrational magic, could have observed the human anatomy so meticulously? How could savages have expressed such noble feelings towards both men and women? Faced with such an unbearable paradox, total denial was their only answer.

Hence, when the German archaeologist Leo Frobenius presented the bronze heads, western experts refused to believe in the existence of an African civilization capable of leaving artifacts of a quality they recognized as comparable to the best artistic achievements of ancient Rome or Greece. In a desperate attempt to explain what passed for an anomaly, Frobenius, without the slightest semblance of proof, came up with the theory that these heads had been cast by a Greek colony founded in the XIIIth century BC, and that the latter could be at the origin of the old legend of the lost civilization of Atlantis, a narrative immediately adopted in chorus by the mass media…

Bronze

What first shocked Western experts was that these were not carved wood but sophisticated bronze heads (about 70 % copper, 16.5 % zinc and 11.3 % lead).

Given the extreme scarcity of copper ore in Nigeria, these objects demonstrate that the region had trade relations with distant countries. The ore is believed to have come from Central Europe, northwest Mauritania, the Byzantine Empire or, via the Niger River, from Timbuktu where the ore arrived by camel from southern Morocco.

If during the Neolithic period, copper, gold and silver nuggets were hammered cold or hot, it is only starting from the Bronze Age that man develops the science of real metallurgy. From ores, he was then able to extract metals thanks to a precise heat treatment, made possible by the experience of the ceramists of the time, great experts in the construction of high temperature ovens.

Copper only melts at 1083° Celsius, but by adding tin (which melts at 232°) and lead (which melts at 327°), it is possible to obtain bronze at 890° and brass at 900°. The terracotta is made at low temperature, around 600 to 800°. It should be underlined that in China, since the Shang Dynasty (1570-1045 BC), certain types of porcelain obtained much higher temperatures, between 1000 and 1300° Celsius, obtained thanks to the use of charcoal.

The oldest traces of ceramics in sub-Saharan Africa are thought to date back to more than 9000 BC, and perhaps earlier. Bu some fragmentary shards have been discovered in West Africa, in this case in Mali, and considered dating from 12000 BC. Ceramics also were produced further south, notably by the Nok culture in northern Nigeria at the beginning of the first millennium BC.

Lost-wax casting

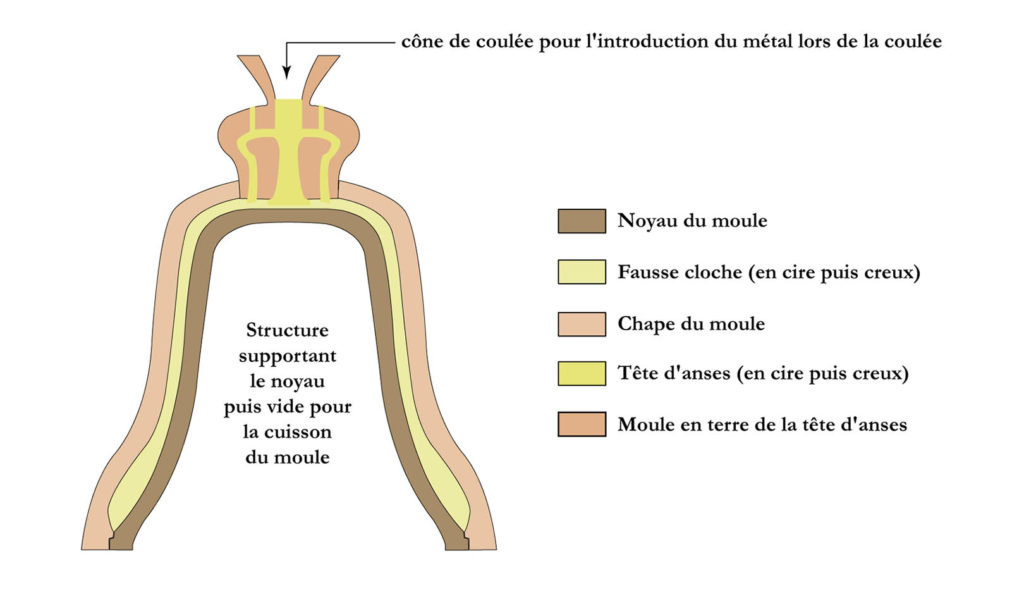

What also shocked the experts was that the technique used to make them was the quite sophisticated so-called « lost-wax casting » or “cire perdue” technique, a high precision molding process that is still used today to make church bells.

First, a model was made out of wax. This was covered with fine clay to form a mold, which was then heated so that the wax melted and ran away. Molten metal was poured into the clay mold which would be broken open to release the complete object.

Clearly, the foundries producing these artifacts required a highly skilled and well organized professional labor force.

The exceptional know-how and skills of the bronze founders of Ife was preceded by those of Igbo-Ukwu in eastern Nigeria where in 1939 a tomb filled with artifacts dating from the IXth century was discovered, revealing the existence of a powerful and refined kingdom mastering the famous lost-wax casting technique, but which so far could not be linked to any other culture in the region.

The oldest known example of the lost-wax technique comes from a 6,000-year-old wheel-shaped copper amulet found at Mehrgarh in today’s Pakistan. Although China, Greece and Rome mastered this technique, it was not until the Renaissance that it made its return to Europe.

Ife, an organized state

In reality, the art of Ife challenged the colonial theory that Africa was a virgin land, populated by animals and a few primitive tribes who had never taken their first steps in « history ».

Indeed, any evidence showing the existence of empires, kingdoms or great states on the African continent that allowed Africans to govern themselves peacefully for centuries could only de-legitimize the « civilizing mission » of colonialism.

However, according to oral traditions, Ife was founded in the 9th-10th centuries by Oduduwa, through the fusion of 13 villages into a single city becoming the hearth of Yoruba mythology, who considers Ife as the cradle of humanity and the center of the world.

Recognized as a minor god, Oduduwa became the first Ooni (King) and had an Aafin (palace) built. He ruled with the help of the isoro, former village chiefs who had recovered a religious title and were subject to royal political authority.

According to the same oral traditions, Oduduwa is said to have been an exiled Prince of a foreign people, who left his homeland and traveled south with his suite, settling among the Yoruba around the XIIth century. His religious faith, that he brought with him, was so important to him and his followers that it would have been the cause of their exodus in the first place.

Oduduwa’s land or country of origin remains a matter of debate. For some, he comes from Mecca, for others from Egypt, as the technical skills he brought with him are supposed to demonstrate.

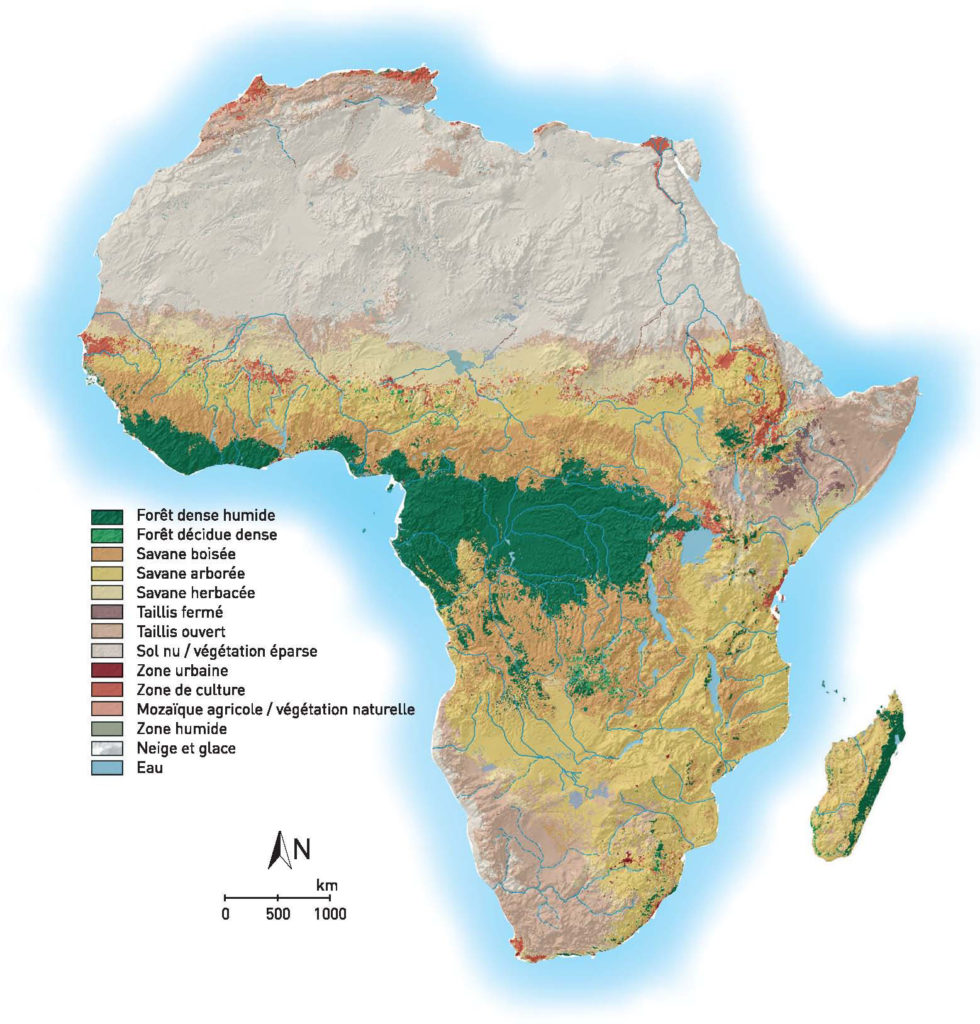

So far, most historians have looked to influences arriving by sea and waterways. However, it is a very plausible hypothesis that travel routs through the savanna, could have connected the Niger Delta with the Nile, like a sort of great transcontinental land-bridge, passing notably via Chad, a region where thousands of early cave paintings testify the vivacity of pictorial creativity.

As our good friend Kotto Essomé repeatedly underlined, African states often prospered along the climatic zones, following “horizontally” the latitudes. Colonial borders were deliberately drawn (laterally or “vertically”) to break the natural boundaries of pre-colonial African states.

Now, as this map clearly indicates, a horizontal “ribbon” of habitable urban areas, on the borderline between the herbaceous and wooded savanna, stretches over the entire continent from the Atlantic till the Southern Nile. Unsurprisingly, this particular climatic and geographical area might have been optimally suited for both hunting, agriculture and cattle raising.

From their part, the Edo people of Benin City believed that Oduduwa was in fact a prince of their extraction, who would have fled Benin during a fight over royal succession. This is why one of his descendants, Prince Oramiyan, would have been allowed to return and found the dynasty ruling the Kingdom of Benin. Prince Oramiyan was thus the first oba of Benin, successfully replacing the Ogiso monarchical system that had reigned until then.

Metallurgy

What deserves attention here is the fact that metallurgy occupies a central place in Ife. Oduduwa had a forge in his Royal palace (Ogun Laadin). Kings from different kingdoms installed their forges within the royal palace, showing the strong symbolic relationship between power and metallurgy.

Contrary to what happened on other continents, the Iron Age in Africa would have preceded the Copper Age in some regions. The oldest indications documenting the transformation of iron ore in Africa date back to the third millennium BC. They are the archaeological sites of Egaro in eastern Niger and Giza and Abydos in Egypt. While the site of Buhen in Egyptian Nubia (- 1991), after working iron, became a « copper factory », the sites of Oliga in Cameroon (-1300) and Nok in Nigeria (-925) testify clearly of a dynamic metallurgical activity.

As we have seen, bronze casting techniques demonstrate the existence of a very advanced technological know-how. Ife will also be a major center for glass production, especially glass beads. The waste material of this ancestral production, made up of parts of crucibles covered with molten glass, will be looked for in the XIXth century by the inhabitants of the region, although the origin of the glass beads was neglected.

Recent archaeological excavations have shown that the settlements of this area are very ancient. But as we have seen, it was only at the beginning of the 2nd millennium that developments in the field of metallurgy would have made it possible to improve agricultural tools and generate surplus food. Yam, cassava, maize and cotton are cultivated here, the latter giving birth to an important cloth weaving industry.

Hence, the city of Ife experienced a rapid demographic expansion thanks to this rise in agricultural productivity, itself the fruit of the mastery of an increased energy density allowing the transformation of « stones » (ores) into useful resources.

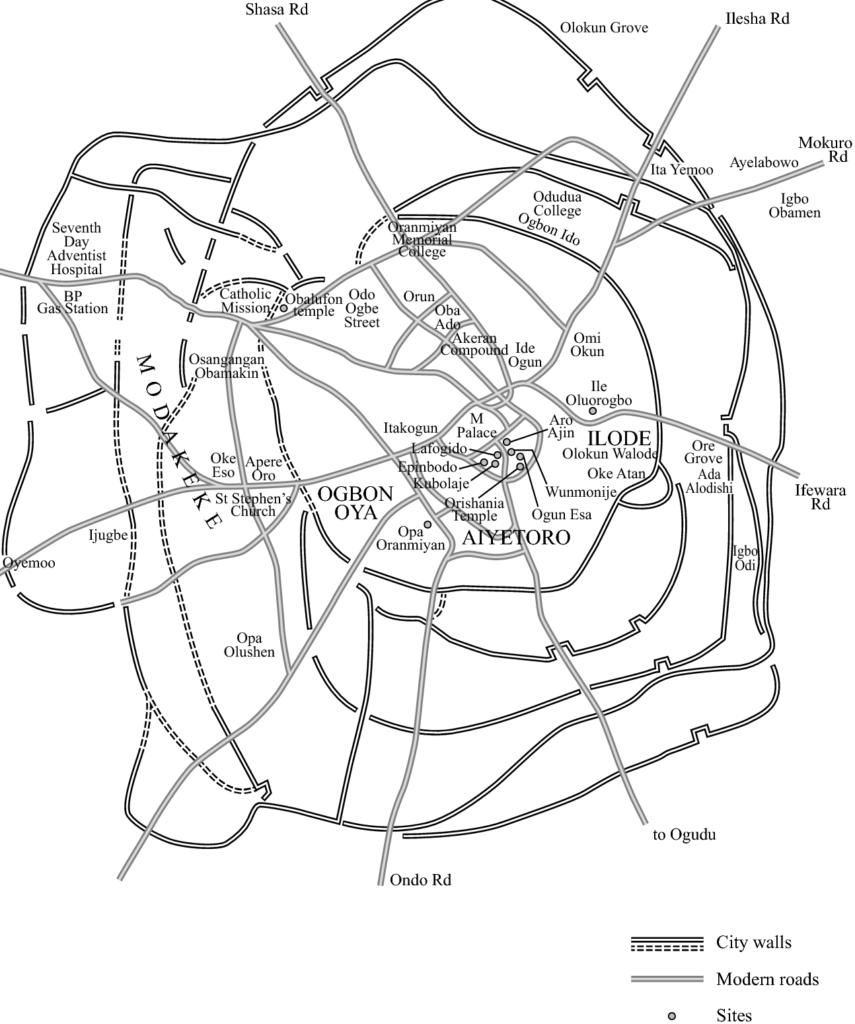

The medieval urbanization of Ife is today widely attested by the existence of numerous enclosures made of ditches and embankments, which seem to indicate the various spaces that have experienced a demographic concentration and the existence of a political body powerful enough to implement such great infrastructure programs.

Interesting, as a successful centralized state, Ife became increasingly a model for other states in the region and beyond. Several descendants and captains of Oduduwa founded their own kingdoms based on the same model and relying on the same legitimacy. The monarchical experience of Ife is exported with its cultural framework. The adé ilèkè, a crown of glass beads symbolizing royal power, is found in most monarchies in the region.

In total, depending on the sources, an estimated 7 to 20 kingdoms make up the Yoruba world in the first half of the second millennium AD.

- Oyo State in Nigeria was one of such powerful Yoruba city-states.

- Another example, the Kingdom of Ketou, currently in the southeast of Benin, is supposed to have been founded around the XIVth century by an alleged descendant of Oduduwa. He is said to have left Ife with his family and other members of his clan and moved westward, eventually settling in the city of Aro, northeast of the city of Ketou. Aro quickly became too small for the growing population, and the decision was made to settle in Ketou. King Ede therefore left Aro with 120 families and settled in this city.

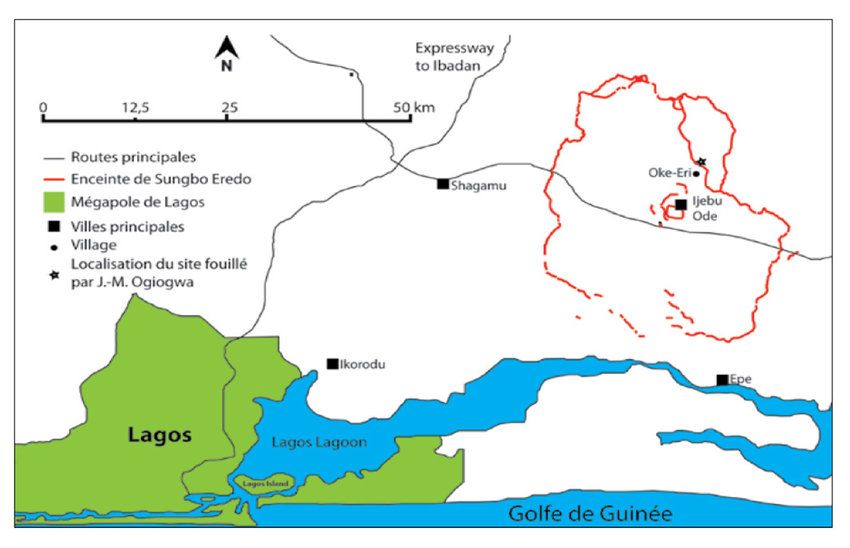

- Another demonstration of Yoruba building science is the Sungbo Eredo Wall, near the Nigerian capital Lagos, a system of walls and ditches built in the XIVth century and located southwest of the town of Ijebu Ode, in Ogun State, southwestern Nigeria. More than 160 km (100 miles) long, these fortifications, some as high as 20 meters (65 feet), consist of a smooth-walled ditch that forms an inner moat in relation to the walls that overhang it. The ditch forms an irregular ring (Map) around the lands of the ancient kingdom of Ijebu. This ring is about 40 km in the north-south direction and 35 km in the east-west direction, which is the equivalent of the Paris périphérique ! Invaded by vegetation, the construction today looks like a green tunnel.

From Ife to the Kingdom of Benin

In the XIVth century, Ife experienced a demographic collapse, characterized by the abandonment of certain enclosures and a strong advance of the forest into formerly residential areas. There was also a break in the transmission of know-how and artisan techniques.

This demographic collapse has been explained as the result of a Black Plague, according to some authors, who draw a parallel with the pandemic waves hitting Europe at the same period.

Part of the inhabitants of Ife were able to take refuge and bring their know-how in metallurgy to the Kingdom of Benin, which lasted for seven hundred years, from the XIIth century until its invasion by the British Empire at the end of the XIXth century. Benin was a coastal West African city-state dominated by the Edos, an ethnic group whose dynasty still survives today.

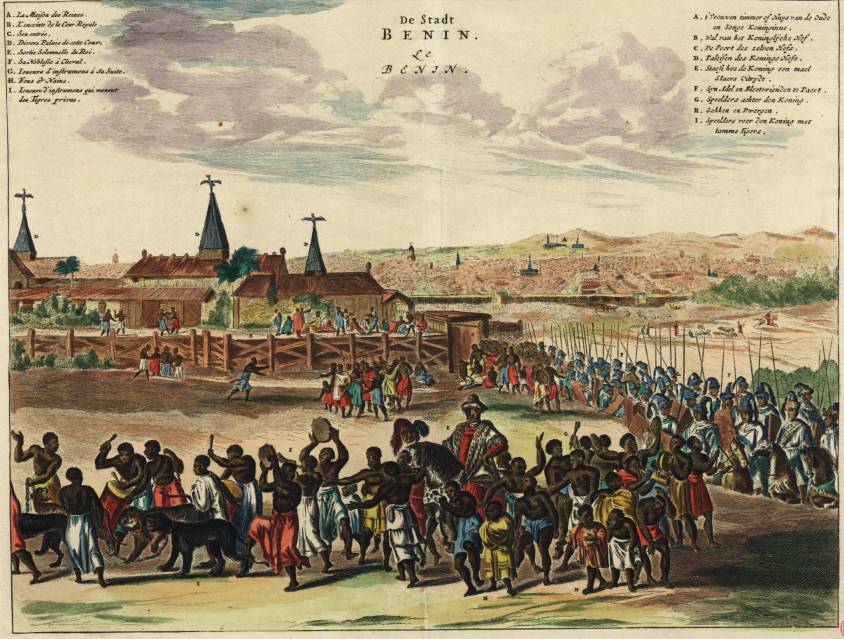

Its territory covers to present-day Benin, plus part of Togo and southwestern Nigeria, where today « Benin City », a historic port on the Benin River, is located. In the heart of the city, the royal residence with monumental proportions translated visually the importance given to political, spiritual and traditional power.

Benin City, a marvel

The social organization of the city impressed European visitors at the end of the XVth century. As a major regional economic trading pole, Benin was full of ivory, pepper and slaves. Benin offered the Europeans palm oil (the oil palm growing abundantly in the region). In exchange, they requested, and obtained guns, allowing the modernization of the Beninese armament.

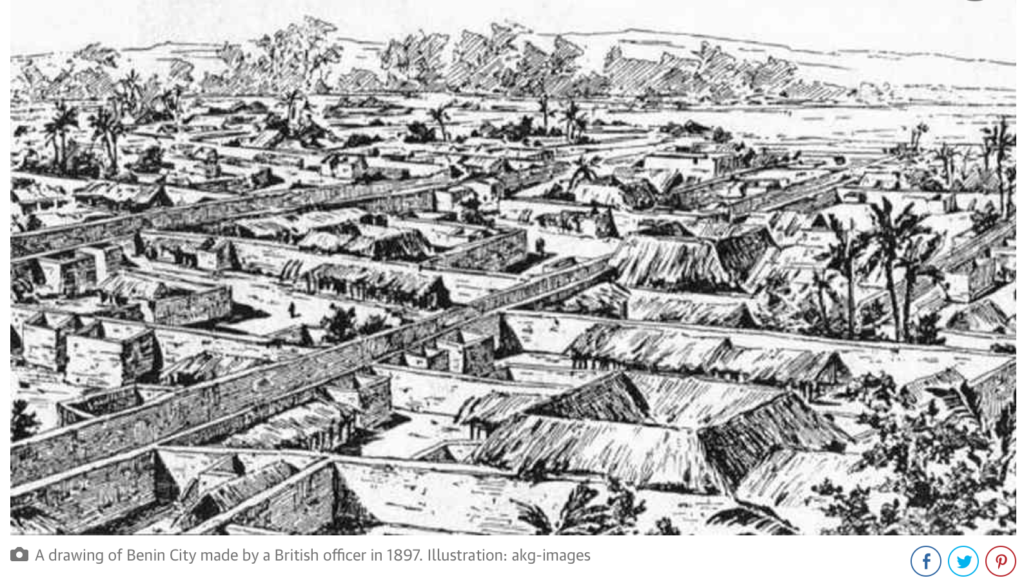

Located in a plain, Benin City is surrounded by massive walls to the south and deep ditches to the north. Beyond the city walls, many other walls have been erected that organize the entire region of the capital into some 500 separate boroughs.

In 2016, an article published by The Guardian recounted the lost splendor of the city. The paper reported:

“The Guinness Book of Records (1974 edition) described the walls of Benin City and its surrounding kingdom as the world’s largest earthworks carried out prior to the mechanical era. According to estimates by the New Scientist’s Fred Pearce, Benin City’s walls were at one point “four times longer than the Great Wall of China, and consumed a hundred times more material than the Great Pyramid of Cheops”.

Pearce writes that these walls “extended for some 16,000 km in all, in a mosaic of more than 500 interconnected settlement boundaries. They covered 6,500 sq km and were all dug by the Edo people … They took an estimated 150 million hours of digging to construct, and are perhaps the largest single archaeological phenomenon on the planet”.

Benin City was also one of the first cities to have a semblance of street lighting. Huge metal lamps, many feet high, were built and placed around the city, especially near the king’s palace. Fueled by palm oil, their burning wicks were lit at night to provide illumination for traffic to and from the palace.

When the Portuguese first “discovered” the city in 1485, they were stunned to find this vast kingdom made of hundreds of interlocked cities and villages in the middle of the African jungle.

In 1691, the Portuguese ship captain Lourenco Pinto observed:

“Great Benin, where the king resides, is larger than Lisbon; all the streets run straight and as far as the eye can see. The houses are large, especially that of the king, which is richly decorated and has fine columns. The city is wealthy and industrious. It is so well governed that theft is unknown and the people live in such security that they have no doors to their houses.”

In contrast, London at the same time is described by Bruce Holsinger, professor of English at the University of Virginia, as being a city of “thievery, prostitution, murder, bribery and a thriving black market made the medieval city ripe for exploitation by those with a skill for the quick blade or picking a pocket”.

African fractals

Benin City’s planning and design was done according to careful rules of symmetry, proportionality and repetition now known as fractal design. The mathematician Ron Eglash, author of African Fractals – which examines the patterns underpinning architecture, art and design in many parts of Africa – notes that the city and its surrounding villages were purposely laid out to form perfect fractals, with similar shapes repeated in the rooms of each house, and the house itself, and the clusters of houses in the village in mathematically predictable patterns.

As he puts it:

“When Europeans first came to Africa, they considered the architecture very disorganized and thus primitive. It never occurred to them that the Africans might have been using a form of mathematics that they hadn’t even discovered yet.”

At the center of the city stood the king’s court, from which extended 30 very straight, broad streets, each about 120-ft wide. These main streets, which ran at right angles to each other, had underground drainage made of a sunken impluvium with an outlet to carry away storm water. Many narrower side and intersecting streets extended off them. In the middle of the streets were turf on which animals fed.

“Houses are built alongside the streets in good order, the one close to the other,” writes the XVIIth-century Dutch visitor Olfert Dapper. “Adorned with gables and steps … they are usually broad with long galleries inside, especially so in the case of the houses of the nobility, and divided into many rooms which are separated by walls made of red clay, very well erected.”

Dapper adds that wealthy residents kept these walls “as shiny and smooth by washing and rubbing as any wall in Holland can be made with chalk, and they are like mirrors. The upper stores are made of the same sort of clay. Moreover, every house is provided with a well for the supply of fresh water”.

Family houses were divided into three sections: the central part was the husband’s quarters, looking towards the road; to the left the wives’ quarters (oderie), and to the right the young men’s quarters (yekogbe).

Daily street life in Benin City might have consisted of large crowds going though even larger streets, with people colorfully dressed – some in white, others in yellow, blue or green – and the city captains acting as judges to resolve lawsuits, moderating debates in the numerous galleries, and arbitrating petty conflicts in the markets.

The early foreign explorers’ descriptions of Benin City portrayed it as a place free of crime and hunger, with large streets and houses kept clean; a city filled with courteous, honest people, and run by a centralized and highly sophisticated bureaucracy.

The city was split into 11 divisions, each a smaller replication of the king’s court, comprising a sprawling series of compounds containing accommodation, workshops and public buildings – interconnected by innumerable doors and passageways, all richly decorated with the art that made Benin famous. The city was literally covered in it.

The exterior walls of the courts and compounds were decorated with horizontal ridge designs (agben) and clay carvings portraying animals, warriors and other symbols of power – the carvings would create contrasting patterns in the strong sunlight. Natural objects (pebbles or pieces of mica) were also pressed into the wet clay, while in the palaces, pillars were covered with bronze plaques illustrating the victories and deeds of former kings and nobles.

At the height of its greatness in the XIIth century – well before the start of the European Renaissance – the kings and nobles of Benin City patronized craftsmen and lavished them with gifts and wealth, in return for their depiction of the kings’ and dignitaries’ great exploits in intricate bronze sculptures.

“These works from Benin are equal to the very finest examples of European casting technique,” wrote Professor Felix von Luschan, formerly of the Berlin Ethnological Museum. Italian Renaissance artist “Benvenuto Celini could not have cast them better, nor could anyone else before or after him. Technically, these bronzes represent the very highest possible achievement.”

The fatal encounter with « civilization »

Following the Berlin Conference of 1885, where the British, Portuguese, Belgian, German, French, Italian and other European colonial powers shared Africa like a big chocolate cake that they intended to devour, in the name of the immutable laws of the freshly invented science of “geopolitics”, European invasions multiplied and gained in brutality.

Thus, following the king of Benin’s refusal to cede to the British the national monopoly on the production of palm oil and other products, Benin City was looted, burned and reduced to ashes during a British punitive expedition in 1897. The king (the oba) is arrested and forced into exile and thousands of beautiful « bronzes of Benin », though less realistic than those of Ife, are stolen, sold and partly lost.

They end up on the art market and in museums, including the British Museum (700 objects) and the Berlin Museum of Ethnology (500 pieces). The British government itself sells some of them « to cover the cost of the expedition« .

So, while some clearly entered history with their beautiful art, others exited civilization with their barbarian crimes.

Summary bibliography:

- Ifè, une civilisation africaine, Frank Willett, Jardin des Arts/Tallandier, Paris 1971;

- General History of Africa, Présence africaines/Edicef/Unesco, Paris 1987;

- Atlas historique de l’Afrique, Editions du Jaguar, Paris 1988;

- L’Afrique ancienne, de l’Acus au Zimbabwe, under the direction of François-Xavier Fauvelle, Belin/Humensis, Paris 2018.