Étiquette : Nile

The science of Oases, from the Indus Valley to Persian qanats

Presentation of Karel Vereycken at the first panel discussion of the « Water for Peace » seminar organized by the Schiller Institute on January 9, 2024 in Paris.

While the dog was domesticated as early as 15,000 years BC, we associate the first human activities aimed at managing water with the Neolithic period, which began around 10,000 BC.

It is thought to be the moment at which mankind moved from a « tribal subsistence economy of hunter-gatherers » to agriculture and animal husbandry, giving rise to villages and cities, where pottery, weaving, metallurgy and the arts would start blooming.

Key to this, the domestication of animals. The goat was domesticated around 11,000 BC, the cow around 9,000 BC, the sheep around -8,000 BC, and finally the horse around 2,200 BC in the steppes of Ukraine.

The oldest archaeological sites showing agricultural activities and irrigation techniques were discovered in the Indus Valley and the « Fertile Crescent ».

The site of Mehrgarh, in the Indus Valley, now Pakistan Balochistan, discovered in 1974 by François and Cathérine Jarrige, two French archaeologists, demonstrates important agricultural practices from 7000 BC onward.

Cotton, wheat and barley were grown, and beer was brewed. Cattle, sheep and goats were raised. But Mehrgarh was much more than that.

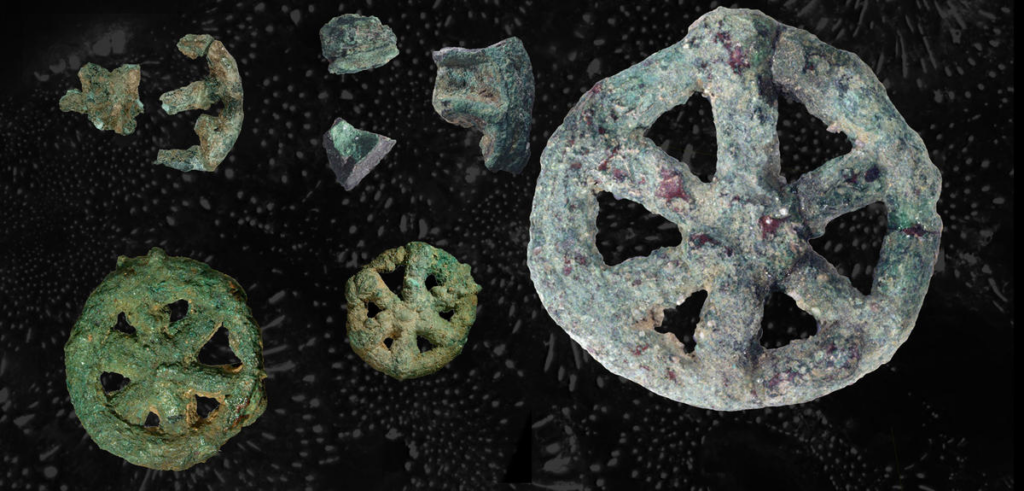

Contradicting the linear « developmental » schema, since we’re in the middle of the Neolithic, Mehrgarh is also home to the oldest pottery in South Asia and, above all, to the “Mehrgahr amulet”, the oldest bronze object casted with the « lost-wax » method.

The first seals made of terracotta or bone and decorated with geometric motifs were found here.

On the technological side, tiny bow drills were used, possibly for dental treatment, as evidenced by the pierced teeth of some skeletons found on site.

At the same time, or shortly afterwards, around 6000 B.C., Mesopotamia, between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, witnessed rapid urban development in terms of demographics, institutions, agriculture, techniques and trade.

A veritable « fertile crescent » emerged in the region stretching from Sumer to Egypt, passing through the whole of Mesopotamia and the Levant, i.e. Syria and the Jordan Valley.

Irrigation

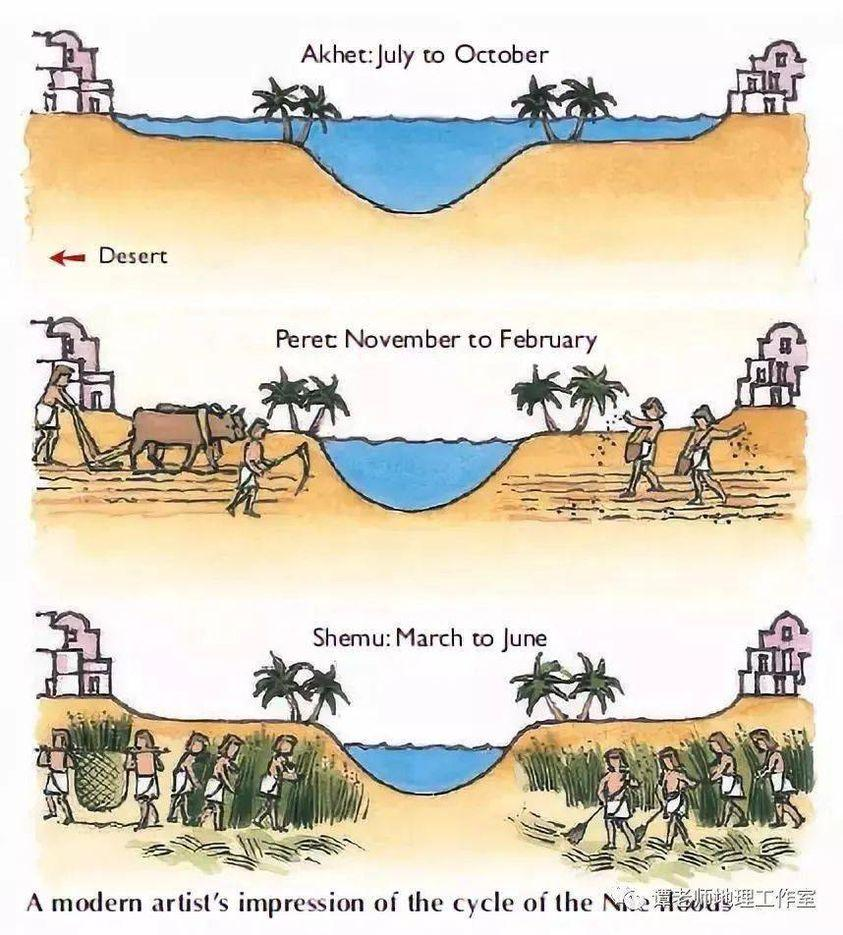

Whether in the Indus Valley, Mesopotamia or Egypt, the earliest irrigation techniques are nothing but retaining as much water as possible when Mother Nature has the sweet kindness to offer it to mankind.

Rainwater was collected in cisterns and, as much as possible, when snowmelt or monsoon rains swell the rivers, the objective was to amplify and steer seasonal « flooding » by canals and trenches carrying the water as far away as possible to areas to be cultivated, while at the same time protecting crops.

In Egypt, for example, where the Nile rises by around 8 meters, the water brings not only moisture but also silt to the soil near the river, providing crops with the nutrients they need to grow and thus maintain the soil’s fertility.

While the Egyptians complained about the harsh labor condition of their farmers, for the Greek historian Herodotus, this was the place in the world where work was least arduous. Of Egypt he says:

“Its soil is black and crumbly, made of silt and alluvium brought from Ethiopia by the river. Certainly, these people are today, of all the human race in Egypt as elsewhere, those who go to the least trouble to obtain their crops.

« They don’t bother to plough and weed. When the river has come of its own accord to water their fields and, its task done, has withdrawn, each man sows his land and lets the pigs loose: by trampling, the beasts sink the seeds into the earth, and the man has only to wait for the harvest.”

In Mehrgarh, where agriculture was born from 7000 BC, the work was indeed far more demanding.

However, the drainage system around the village and the rudimentary dams to control water-logging indicate that the inhabitants understood most of the basic principles involved. The cultivation of cotton, wheat and barley, as well as the domestication of animals, show that they were also familiar with canals and irrigation systems.

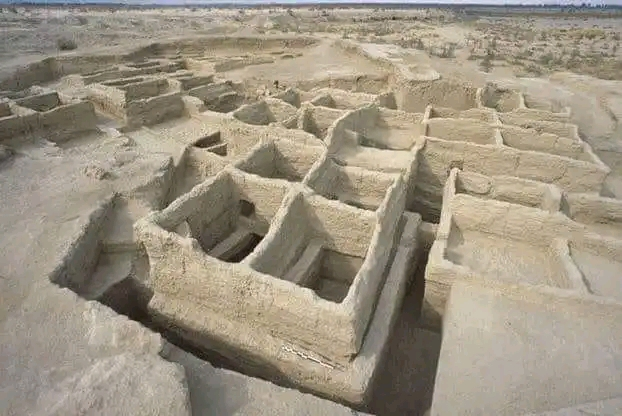

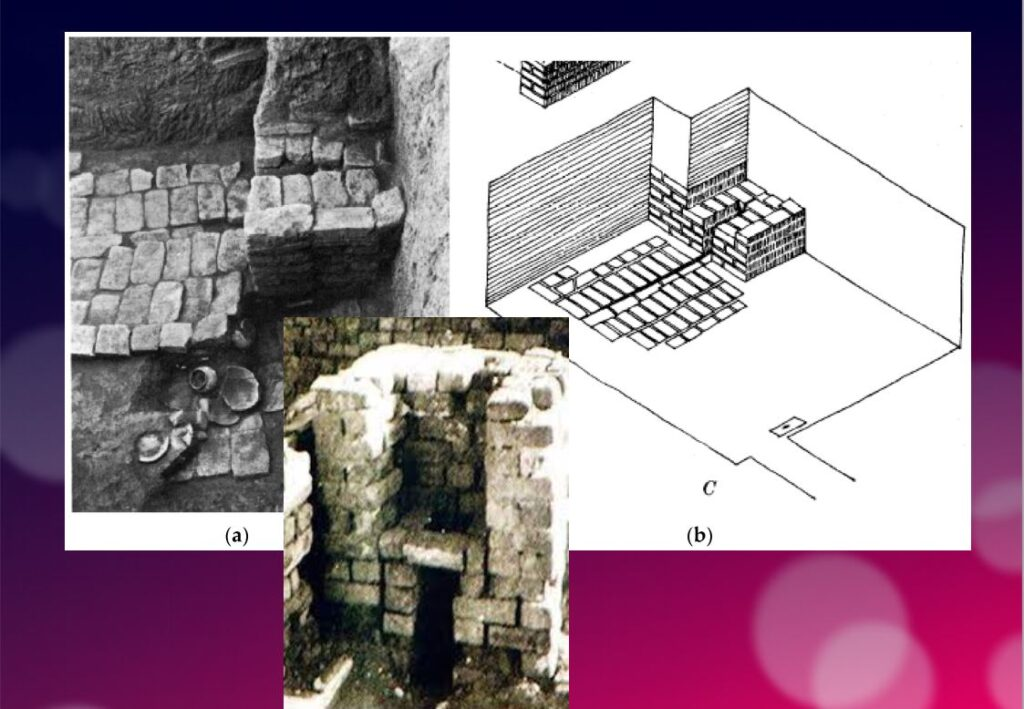

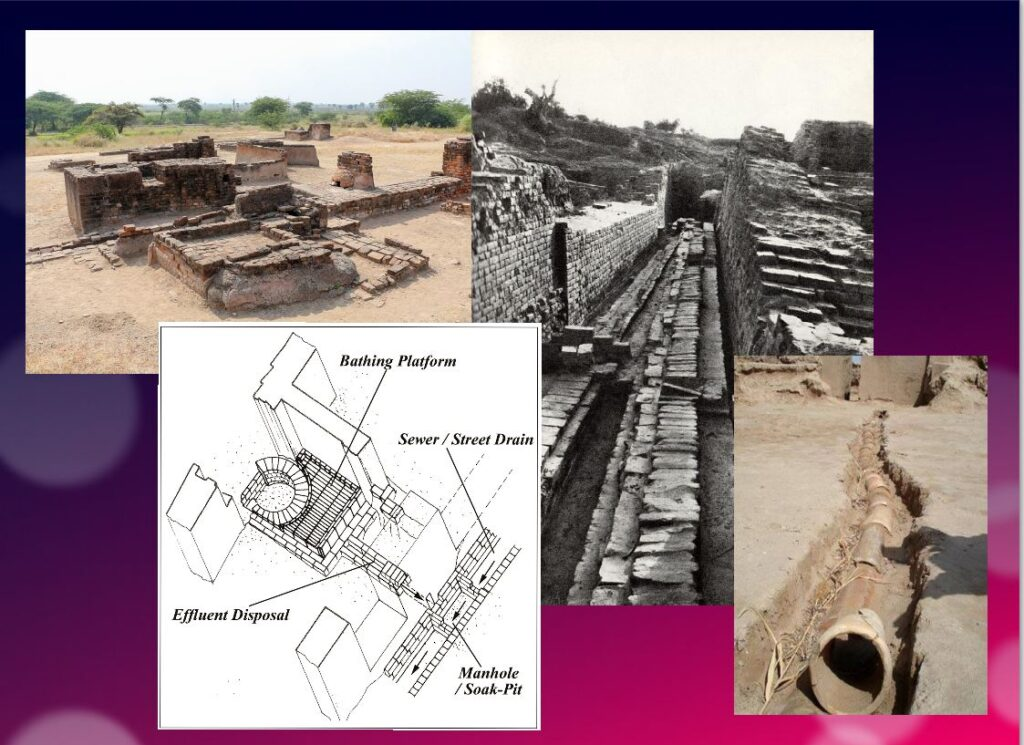

Constantly refined, this know-how enabled the civilization of the Indus Valley to create great cities that impress us by their modernity, notably Harappa and Mohenjo Daro, a city of 40,000 inhabitants with a public bath in its center, not a palace.

Pioneers of modern hygiene, these towns were equipped with small containers where residents could deposit their household waste.

Anticipating our « all-to-the-sewer » systems imagined in the early XVIth century by Leonardo da Vinci, for example in his plans for the new french capital of Romorantin, many towns had public water supplies as well as an ingenious sewage system.

In the port city of Lothal (now India), for example, many homes had private brick bathrooms and latrines. Wastewater was evacuated via a communal sewage system leading either to a canal in the port, or to a soaking pit outside the city walls, or to buried urns equipped with a hole for the evacuation of liquids, which were regularly emptied and cleaned.

Excavations at the Mohenjo Daro site reveal the existence of no fewer than 700 brick wells, houses equipped with bathrooms and individual and collective latrines.

Many of the city’s buildings had two floors or more. Water trickled down from cisterns installed on the roofs was channeled through closed clay pipes or open gutters that emptied into the covered sewers beneath the street.

This hydraulic and sanitary know-how was passed on to the civilization of Crete, the mother of Greece, before being implemented on a large scale by the Romans.

It was forgotten with the collapse of the Roman Empire, only to return during the Renaissance.

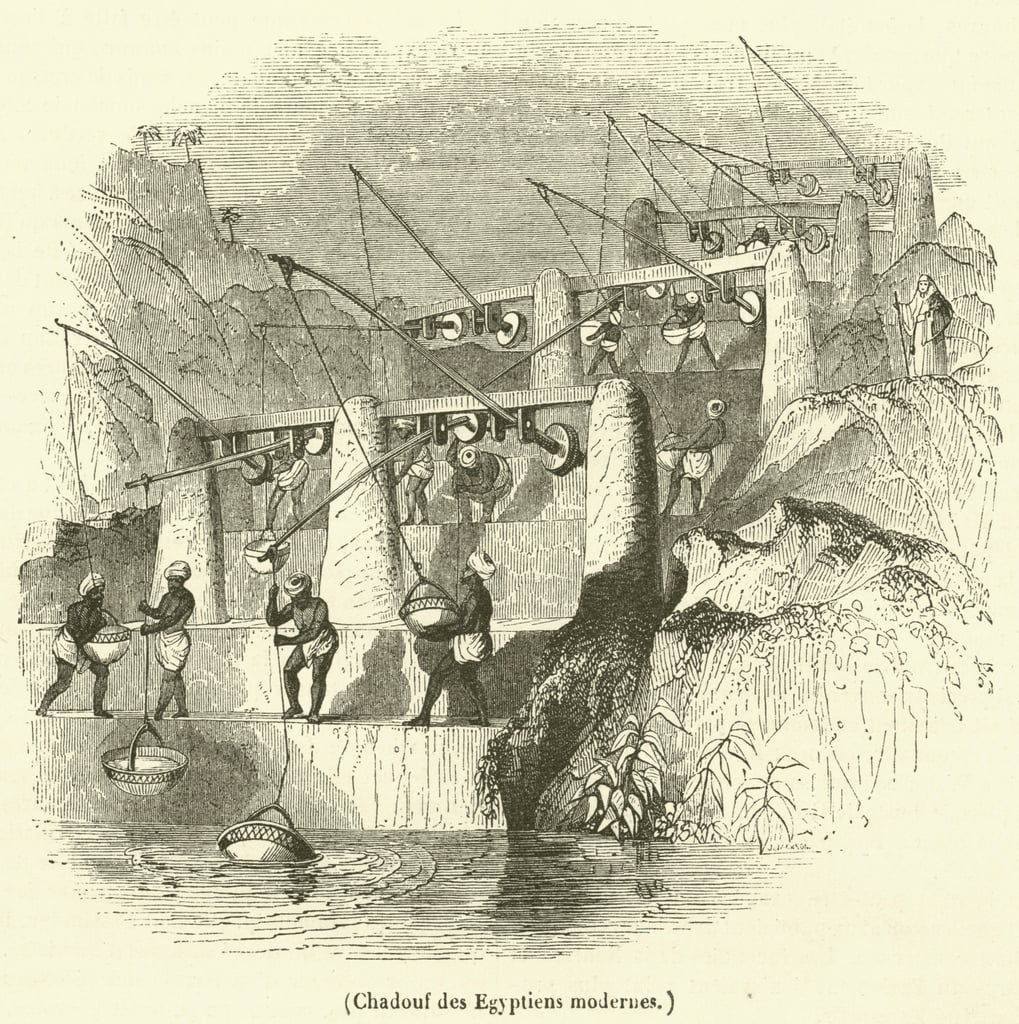

The first human contributions were aimed at maximizing water reservoirs and their gravity-flow capacity. To achieve this, it was necessary to transfer water from a lower level to higher ground and build « water towers ».

To this end, the Mesopotamian « chadouf » was widely used in Egypt, followed by the « Archimedean screw ».

Next came the « saquia » or « Persian wheel », a geared wheel driven by animal power, and finally the « noria », the best-known water-drawing machine, powered by the river itself.

Persian qanats

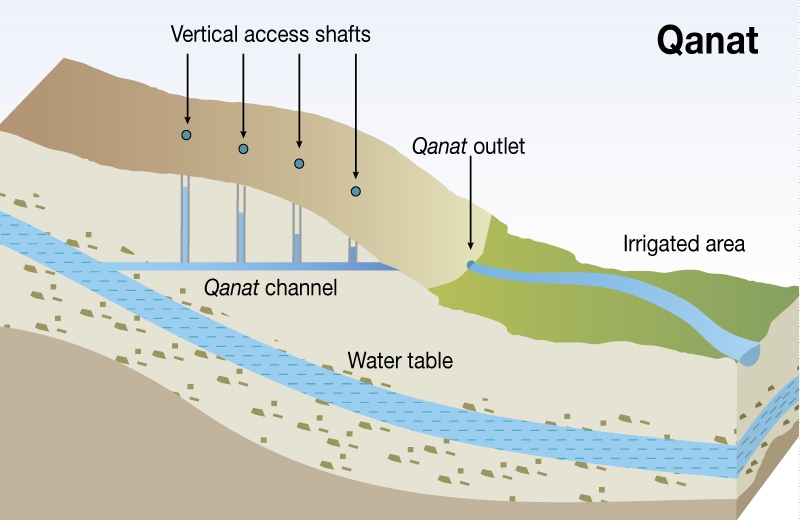

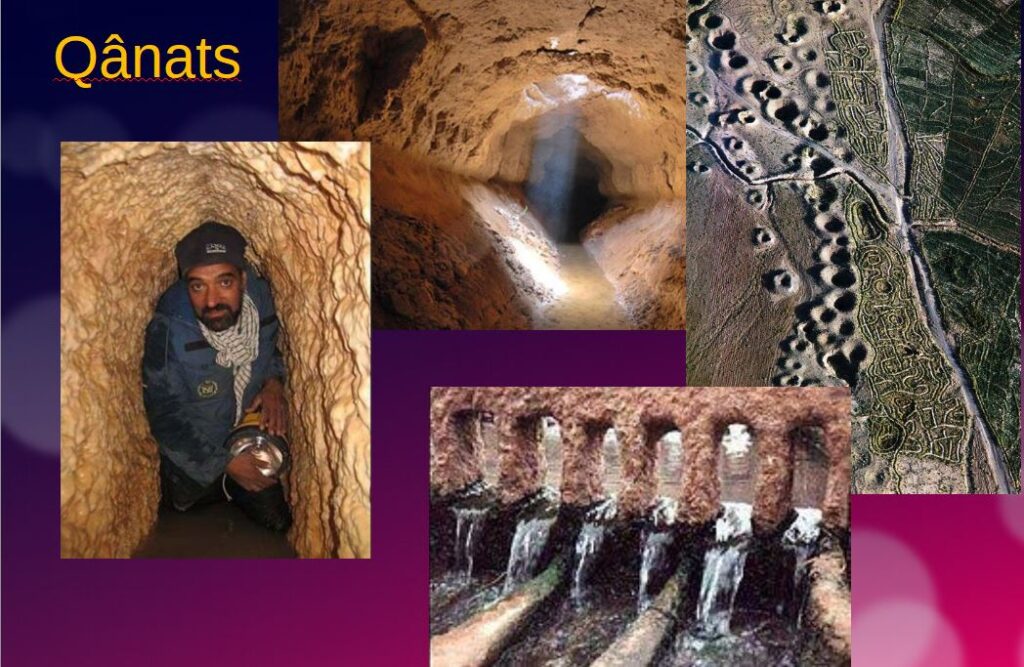

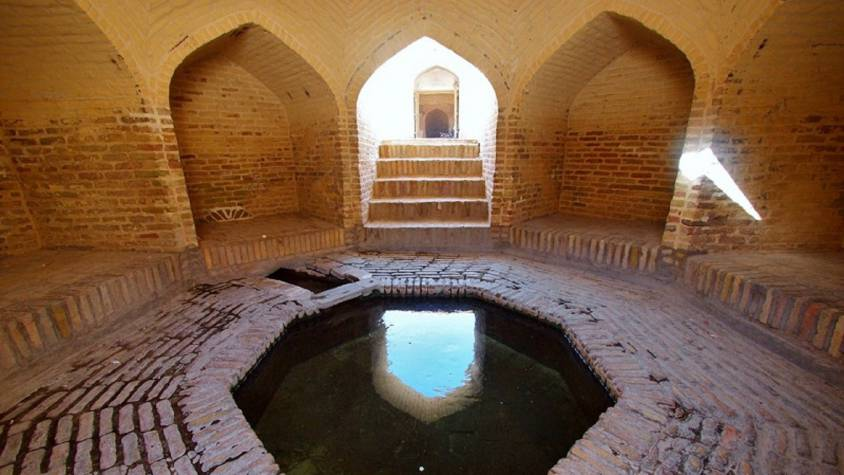

Before Alexander the Great, Persia’s Achaemenid Empire (6th century BC) developed the technique of underground qanats or underground aqueducts. This « draining gallery” cut into the rock or built by man, is one of the most ingenious inventions for irrigation in arid and semi-arid regions.

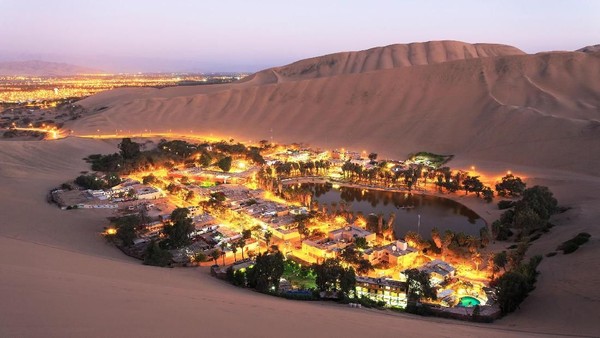

Whatever displeases our environmentalist friends, it’s not nature that magically produces « oases » in the desert.

It’s a scientific man who digs a drainage gallery from a water table close enough to the ground surface, or sometimes from an aquifer that flows into the desert.

On the website of ArchéOrient, archaeologist Rémy Boucharlat, Director of Emeritus Research at the French CNRS, an expert on Iran, explains:

« Whatever the origin of the water, deep or shallow, the gallery construction technique is the same. The first step is to identify the presence of the water, either its underflow near a river, or the presence of a deeper water table on a foothill, which requires the science and experience of specialists.

A motherwell reaches the upper part of this layer or water table, which indicates the depth at which the gallery should be dug. The slope of the gallery must be very shallow, less than 2‰, to ensure a calm and regular flow of water, and to gradually lead the water to the surface, at a gradient much lower than the slope of the piedmont.

The gallery is then excavated, not from the mother well, as it would be flooded immediately, but from downstream, from the arrival point. The pipe is first dug as an open trench, then covered, and finally gradually tunnelled into the ground.

Shafts are dug from the surface at regular intervals, between 5 and 30 m depending on the nature of the terrain, to evacuate soil and provide ventilation during excavation, and to mark the direction of the tunnel.”

Historically, the majority of the populations of Iran and other arid regions of Asia and North Africa depended on the water supplied by qanats; settlement areas thus corresponded to the places where their construction was possible.

The technique offers a significant advantage: as the water moves through an underground conduit, not a drop of water is lost through evaporation.

This technique spread throughout the world under various names: qanat and kareez in Iran, Syria and Egypt, kariz, kehriz in Pakistan and Afghanistan, aflaj in Oman, galeria in Spain, kahn in Balochistan, kanerjing in China, foggara in North Africa, khettara in Morocco, ngruttati in Sicily, bottini in Siena, etc.).

Improved by the Greeks and amplified by the Etruscans and the Romans, the qanats technique was carried by the Spaniards across the Atlantic to the New World, where numerous underground canals of this type still operate in Peru, Chile and western Mexico.

After Alexander the Great, Bactria, covering parts of today’s Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and the northern part of Afghanistan, was even known as the « Oasis civilization » or the “Land of a 1000 Golden Cities”.

Iran boasts it had the highest number of qanats in the world, with approximately 50,000 qanats covering a total length of 360,000 km, about 9 times the circumference of the Earth !

Thousands of them are still operational but increasingly destabilized by erratic well digging and demographic overconcentration.

Shared responsability

In 1017, the Baghdad-based hydrologist Mohammed Al-Karaji provided a detailed description of qanat construction and maintenance techniques, as well as legal considerations about the collective management of wells and pipes.

While each qanat is designed and supervised by a mirab (dowser-hydrologist and discoverer), building a qanat is a collective task that takes several months or years for a village or group of villages. The absolute necessity of collective investment in the infrastructure and its maintenance calls for a superior notion of the common good, an indispensable complement to the notion of private property that rains and rivers are not accustomed to respecting.

In North Africa, the management of water distributed by a khettara (the local name for qanâts) is governed by traditional distribution norms known as « water rights ».

Originally, the volume of water granted per user was proportional to the work involved in building the khettara, and translated into an irrigation period during which the beneficiary could use all the khettara’s flow for his or her fields. Even today, when the khettara has not dried up, this rule of water rights still applies, and a share can be bought or sold. The size of each family’s fields to be irrigated must also be taken into account

All of this demonstrates that good cooperation between man and nature can do miracles if man decides so.

Thank you for your attention and questions welcome!

The splendors of the kingdoms of Ife and Benin

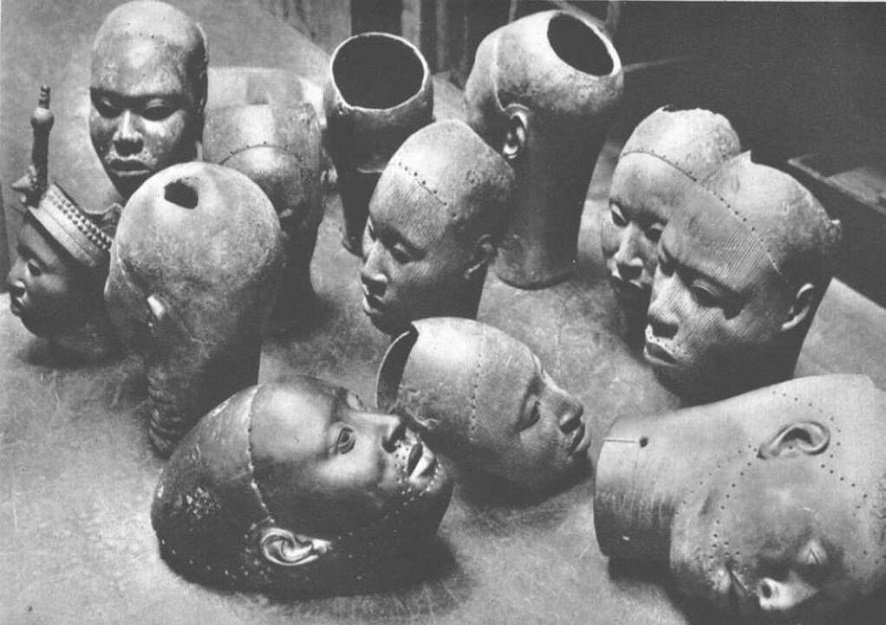

The breathtaking beauty of the XIIth century bronze heads of Ife (Nigeria) challenge the colonial view that Africa was a virgin continent, populated by animals and a few primitive tribes which failed walking their first steps into « history ».

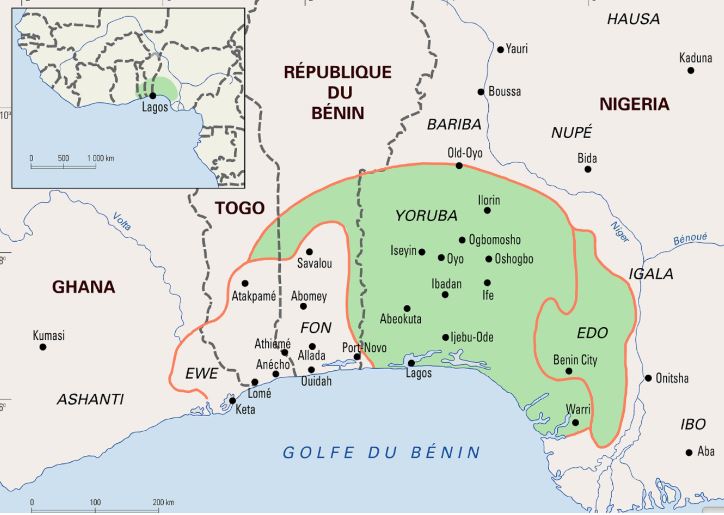

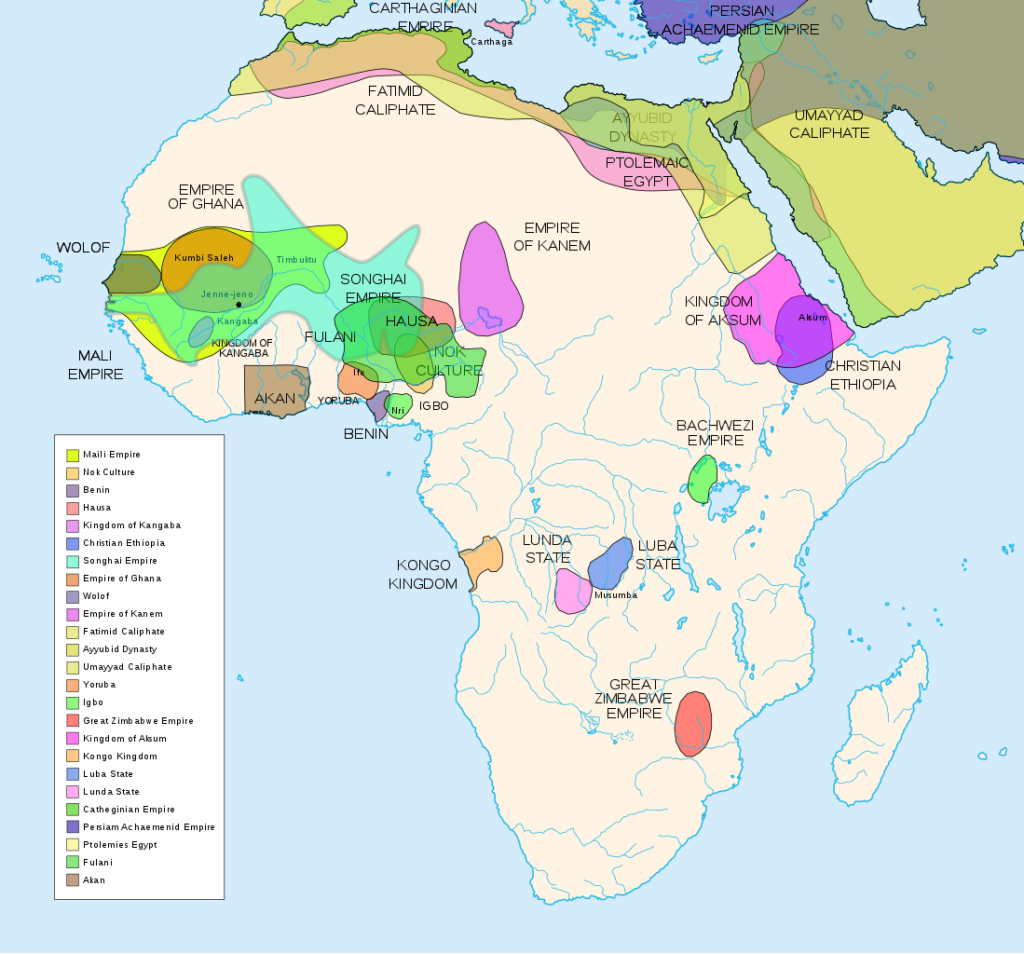

Today inhabited by a half million people, the city of Ife in southwest Nigeria, was formerly the religious center and former capital of the Yoruba people whose prosperity was essentially the fruit of their trade with the peoples of West Africa along the 4200 km long Niger River and beyond.

What some call today “Yorubu-land”, inhabited by some 55 million people, covered some 142,000 km2 comprising vast parts of countries such as today’s Nigeria (76%), Benin (18.9%) and Togo (6.5%).

Today, the Yoruba people live in Ghana, Burkina Faso, Ivory Coast and, since the slave trade, in the United States. It is not surprising, therefore, that yoruba, also the name of one of the three major languages of Nigeria, is also spoken in parts of Benin and Togo, as well as in the West Indies and Latin America, including Cuba and other settlements populated by descendants of African slaves.

An extraordinary discovery

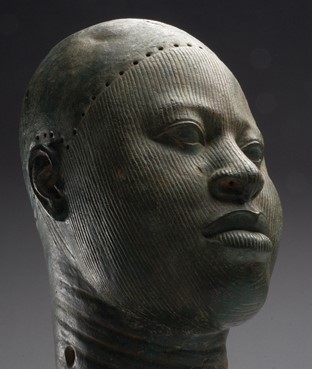

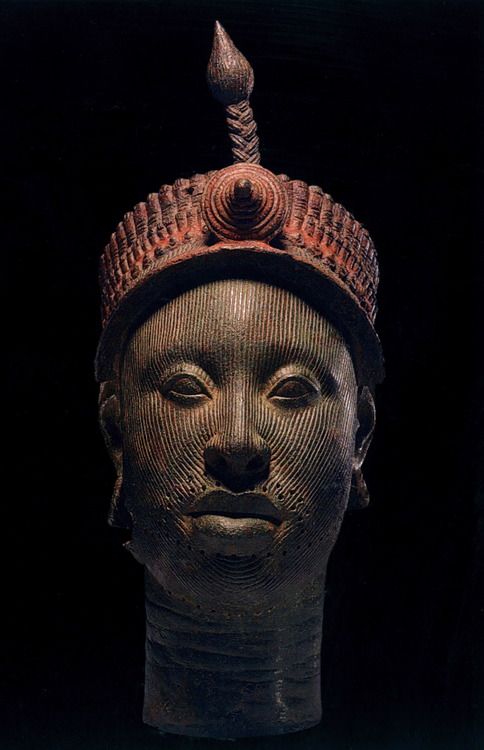

It was in January 1938, during excavation work for the construction of a house, that workers discovered an unusual treasure in the Wunmonije district of Ife. At a mere hundred meters distance away of the site of what once was the Royal Palace, they unearthed thirteen magnificent bronze heads dating from the XIIth century representing a king (an « Ooni« ), some women and courtiers. Others have since been unearthed.

Their faces, except for the lips, are covered with grooves. The hairstyle suggests a complex crown composed of several layers of tubular balls, topped by a crest with a rosette and an « egret ». The surface of this crown bears traces of red and black paint.

These large heads may have been used as effigies of the deceased in funeral ceremonies, which, among the Yoruba, sometimes took place a year after the rapid burial of the dead imposed by the tropical climate.

At the time of the discovery, the extremely naturalist rendering of the heads is considered anachronistic in the art of sub-Saharan Africa, and even more disturbing than the very “classical” i.e. realistic “mummy portraits” (Ist-IInd century) discovered as early as 1887 in the Faiyum depression of Egypt.

Yet a long tradition of figurative sculpture with similar characteristics as the bronze heads of Ife existed before, particularly among the Nok, a people of farmers who mastered iron metallurgy starting from 800 BC.

Hysteria

Since 1938, the « heads of Ife » have provoked reactions close to hysteria in Europe and the West in general.

On the one hand, the « modernists » and the « abstract » artists of the early XXth century, for whom the more abstract a sculpture is and the more distant it is from reality, the more it was considered as typically African. For those who were inspired by African « abstract » art to free themselves from what they considered as materialistic naturalism, the heads of Ife brutally challenged their self-deceiving “smart” narrative.

On the other hand, especially for the supporters of colonial imperialism, this art simply could not be. Frank Willett, at one point the head of the Nigerian Department of Antiquities and author of Ife, an African civilization (Editions Tallandier, 1967), reported that « Europeans visiting Ife frequently wonder how people living in houses of dried mud, with straw roofs, could have made such beautiful objects as the bronzes and terracotta in the museum ». Trying to answer that question, the publisher Sir Mortimer Wheeler replied: “The prejudice is alive and well that artistic creation and sensitivity cannot exist without domestic talent and sanitary comfort!”

The questions of the Europeans were numerous. How, in the XIIth century, could primitive peoples, who had never known an organized form of state, have made bronze heads of such refinement, using techniques that even Europe failed to master at that juncture? How could it have been possible, for tribes, subjected to superstition and irrational magic, could have observed the human anatomy so meticulously? How could savages have expressed such noble feelings towards both men and women? Faced with such an unbearable paradox, total denial was their only answer.

Hence, when the German archaeologist Leo Frobenius presented the bronze heads, western experts refused to believe in the existence of an African civilization capable of leaving artifacts of a quality they recognized as comparable to the best artistic achievements of ancient Rome or Greece. In a desperate attempt to explain what passed for an anomaly, Frobenius, without the slightest semblance of proof, came up with the theory that these heads had been cast by a Greek colony founded in the XIIIth century BC, and that the latter could be at the origin of the old legend of the lost civilization of Atlantis, a narrative immediately adopted in chorus by the mass media…

Bronze

What first shocked Western experts was that these were not carved wood but sophisticated bronze heads (about 70 % copper, 16.5 % zinc and 11.3 % lead).

Given the extreme scarcity of copper ore in Nigeria, these objects demonstrate that the region had trade relations with distant countries. The ore is believed to have come from Central Europe, northwest Mauritania, the Byzantine Empire or, via the Niger River, from Timbuktu where the ore arrived by camel from southern Morocco.

If during the Neolithic period, copper, gold and silver nuggets were hammered cold or hot, it is only starting from the Bronze Age that man develops the science of real metallurgy. From ores, he was then able to extract metals thanks to a precise heat treatment, made possible by the experience of the ceramists of the time, great experts in the construction of high temperature ovens.

Copper only melts at 1083° Celsius, but by adding tin (which melts at 232°) and lead (which melts at 327°), it is possible to obtain bronze at 890° and brass at 900°. The terracotta is made at low temperature, around 600 to 800°. It should be underlined that in China, since the Shang Dynasty (1570-1045 BC), certain types of porcelain obtained much higher temperatures, between 1000 and 1300° Celsius, obtained thanks to the use of charcoal.

The oldest traces of ceramics in sub-Saharan Africa are thought to date back to more than 9000 BC, and perhaps earlier. Bu some fragmentary shards have been discovered in West Africa, in this case in Mali, and considered dating from 12000 BC. Ceramics also were produced further south, notably by the Nok culture in northern Nigeria at the beginning of the first millennium BC.

Lost-wax casting

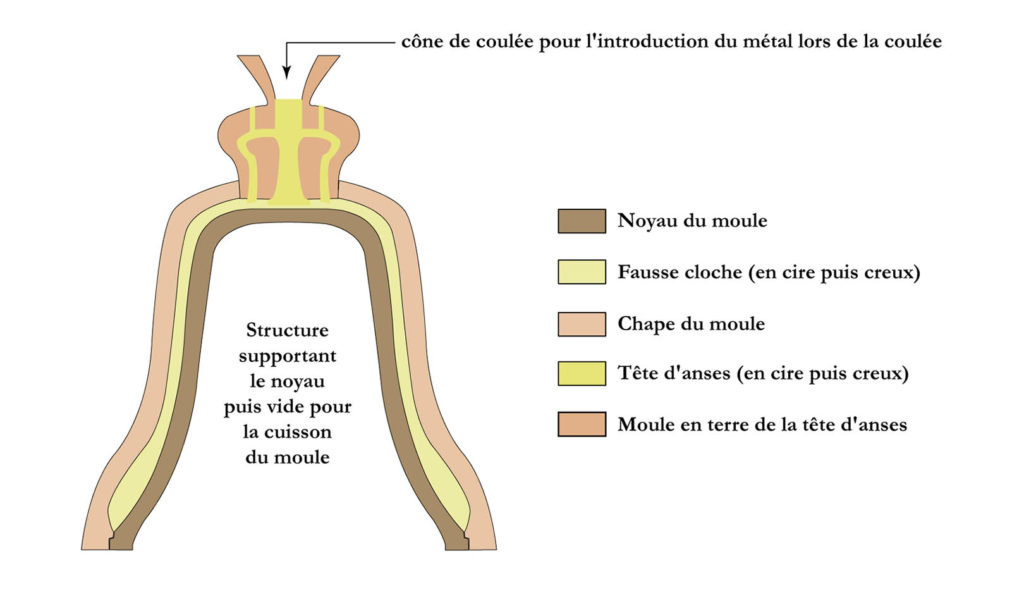

What also shocked the experts was that the technique used to make them was the quite sophisticated so-called « lost-wax casting » or “cire perdue” technique, a high precision molding process that is still used today to make church bells.

First, a model was made out of wax. This was covered with fine clay to form a mold, which was then heated so that the wax melted and ran away. Molten metal was poured into the clay mold which would be broken open to release the complete object.

Clearly, the foundries producing these artifacts required a highly skilled and well organized professional labor force.

The exceptional know-how and skills of the bronze founders of Ife was preceded by those of Igbo-Ukwu in eastern Nigeria where in 1939 a tomb filled with artifacts dating from the IXth century was discovered, revealing the existence of a powerful and refined kingdom mastering the famous lost-wax casting technique, but which so far could not be linked to any other culture in the region.

The oldest known example of the lost-wax technique comes from a 6,000-year-old wheel-shaped copper amulet found at Mehrgarh in today’s Pakistan. Although China, Greece and Rome mastered this technique, it was not until the Renaissance that it made its return to Europe.

Ife, an organized state

In reality, the art of Ife challenged the colonial theory that Africa was a virgin land, populated by animals and a few primitive tribes who had never taken their first steps in « history ».

Indeed, any evidence showing the existence of empires, kingdoms or great states on the African continent that allowed Africans to govern themselves peacefully for centuries could only de-legitimize the « civilizing mission » of colonialism.

However, according to oral traditions, Ife was founded in the 9th-10th centuries by Oduduwa, through the fusion of 13 villages into a single city becoming the hearth of Yoruba mythology, who considers Ife as the cradle of humanity and the center of the world.

Recognized as a minor god, Oduduwa became the first Ooni (King) and had an Aafin (palace) built. He ruled with the help of the isoro, former village chiefs who had recovered a religious title and were subject to royal political authority.

According to the same oral traditions, Oduduwa is said to have been an exiled Prince of a foreign people, who left his homeland and traveled south with his suite, settling among the Yoruba around the XIIth century. His religious faith, that he brought with him, was so important to him and his followers that it would have been the cause of their exodus in the first place.

Oduduwa’s land or country of origin remains a matter of debate. For some, he comes from Mecca, for others from Egypt, as the technical skills he brought with him are supposed to demonstrate.

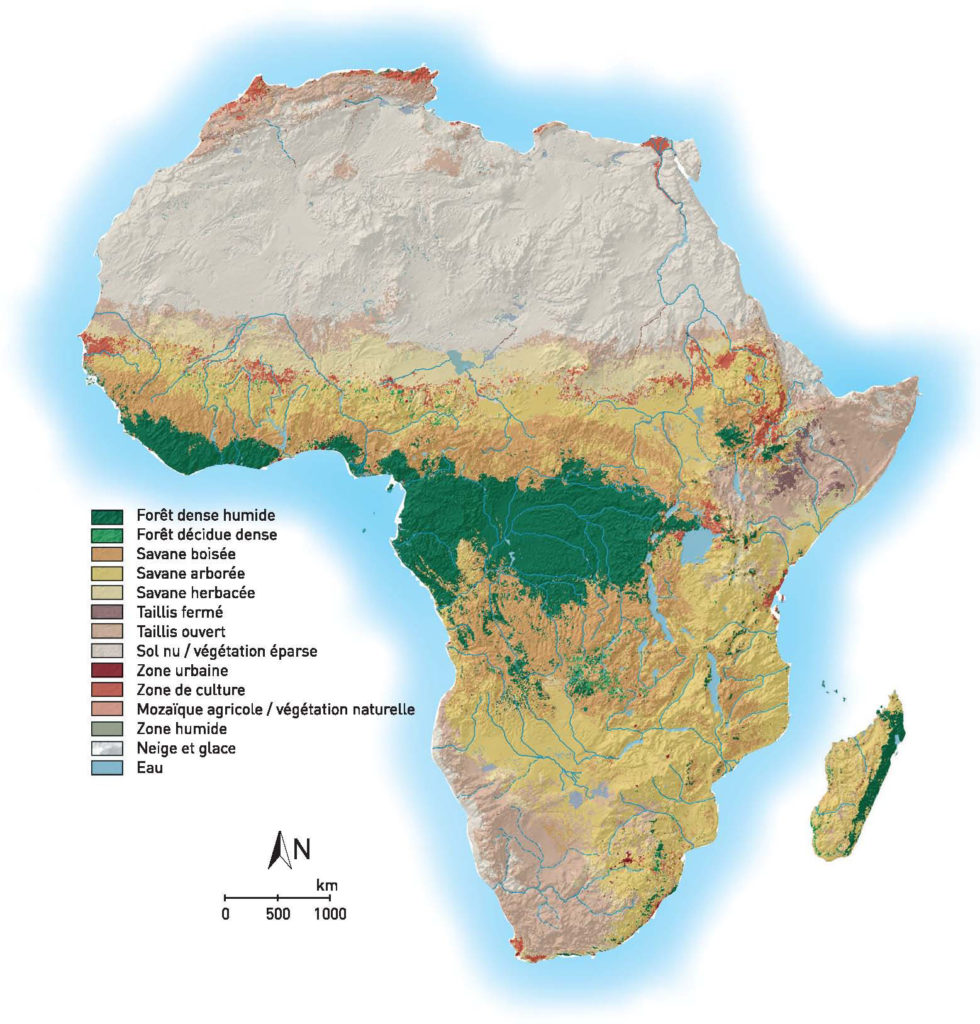

So far, most historians have looked to influences arriving by sea and waterways. However, it is a very plausible hypothesis that travel routs through the savanna, could have connected the Niger Delta with the Nile, like a sort of great transcontinental land-bridge, passing notably via Chad, a region where thousands of early cave paintings testify the vivacity of pictorial creativity.

As our good friend Kotto Essomé repeatedly underlined, African states often prospered along the climatic zones, following “horizontally” the latitudes. Colonial borders were deliberately drawn (laterally or “vertically”) to break the natural boundaries of pre-colonial African states.

Now, as this map clearly indicates, a horizontal “ribbon” of habitable urban areas, on the borderline between the herbaceous and wooded savanna, stretches over the entire continent from the Atlantic till the Southern Nile. Unsurprisingly, this particular climatic and geographical area might have been optimally suited for both hunting, agriculture and cattle raising.

From their part, the Edo people of Benin City believed that Oduduwa was in fact a prince of their extraction, who would have fled Benin during a fight over royal succession. This is why one of his descendants, Prince Oramiyan, would have been allowed to return and found the dynasty ruling the Kingdom of Benin. Prince Oramiyan was thus the first oba of Benin, successfully replacing the Ogiso monarchical system that had reigned until then.

Metallurgy

What deserves attention here is the fact that metallurgy occupies a central place in Ife. Oduduwa had a forge in his Royal palace (Ogun Laadin). Kings from different kingdoms installed their forges within the royal palace, showing the strong symbolic relationship between power and metallurgy.

Contrary to what happened on other continents, the Iron Age in Africa would have preceded the Copper Age in some regions. The oldest indications documenting the transformation of iron ore in Africa date back to the third millennium BC. They are the archaeological sites of Egaro in eastern Niger and Giza and Abydos in Egypt. While the site of Buhen in Egyptian Nubia (- 1991), after working iron, became a « copper factory », the sites of Oliga in Cameroon (-1300) and Nok in Nigeria (-925) testify clearly of a dynamic metallurgical activity.

As we have seen, bronze casting techniques demonstrate the existence of a very advanced technological know-how. Ife will also be a major center for glass production, especially glass beads. The waste material of this ancestral production, made up of parts of crucibles covered with molten glass, will be looked for in the XIXth century by the inhabitants of the region, although the origin of the glass beads was neglected.

Recent archaeological excavations have shown that the settlements of this area are very ancient. But as we have seen, it was only at the beginning of the 2nd millennium that developments in the field of metallurgy would have made it possible to improve agricultural tools and generate surplus food. Yam, cassava, maize and cotton are cultivated here, the latter giving birth to an important cloth weaving industry.

Hence, the city of Ife experienced a rapid demographic expansion thanks to this rise in agricultural productivity, itself the fruit of the mastery of an increased energy density allowing the transformation of « stones » (ores) into useful resources.

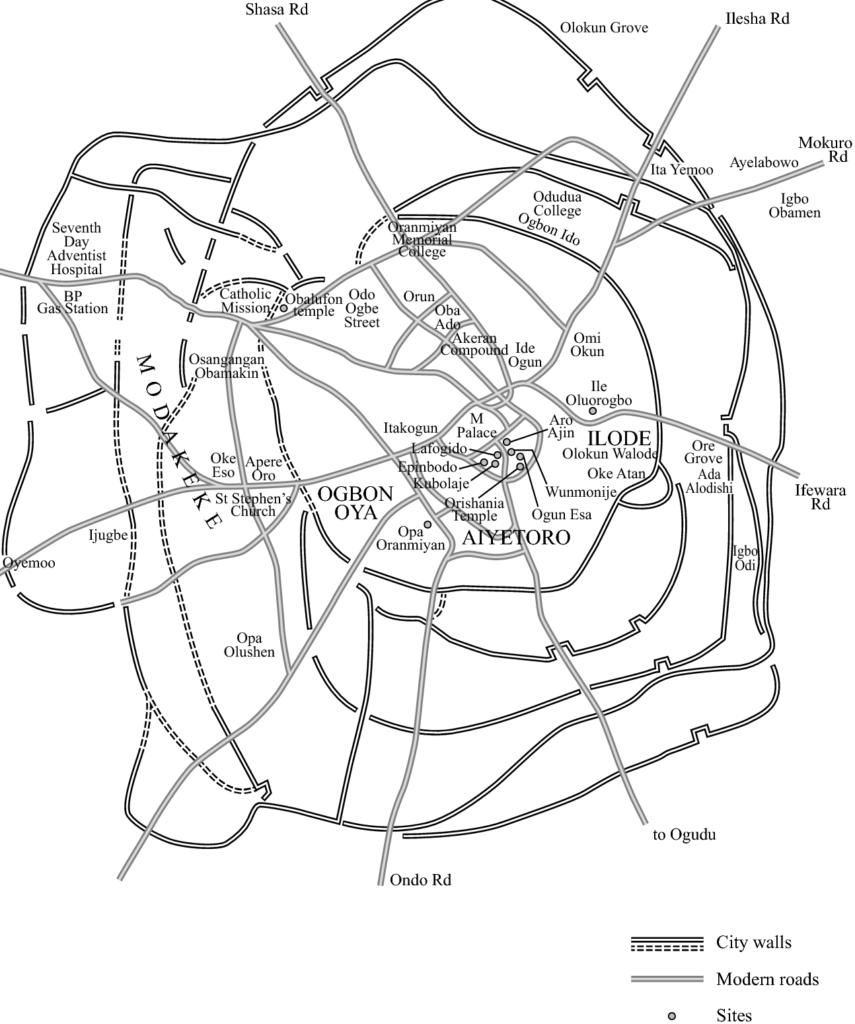

The medieval urbanization of Ife is today widely attested by the existence of numerous enclosures made of ditches and embankments, which seem to indicate the various spaces that have experienced a demographic concentration and the existence of a political body powerful enough to implement such great infrastructure programs.

Interesting, as a successful centralized state, Ife became increasingly a model for other states in the region and beyond. Several descendants and captains of Oduduwa founded their own kingdoms based on the same model and relying on the same legitimacy. The monarchical experience of Ife is exported with its cultural framework. The adé ilèkè, a crown of glass beads symbolizing royal power, is found in most monarchies in the region.

In total, depending on the sources, an estimated 7 to 20 kingdoms make up the Yoruba world in the first half of the second millennium AD.

- Oyo State in Nigeria was one of such powerful Yoruba city-states.

- Another example, the Kingdom of Ketou, currently in the southeast of Benin, is supposed to have been founded around the XIVth century by an alleged descendant of Oduduwa. He is said to have left Ife with his family and other members of his clan and moved westward, eventually settling in the city of Aro, northeast of the city of Ketou. Aro quickly became too small for the growing population, and the decision was made to settle in Ketou. King Ede therefore left Aro with 120 families and settled in this city.

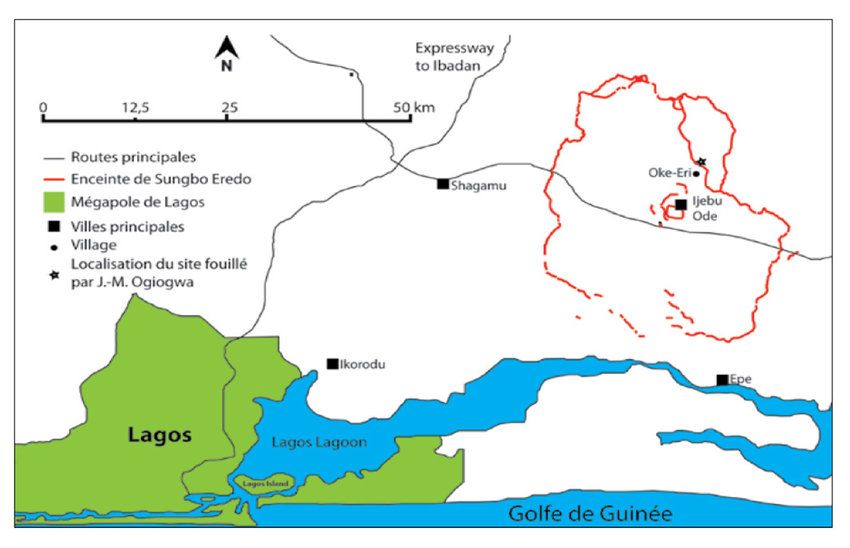

- Another demonstration of Yoruba building science is the Sungbo Eredo Wall, near the Nigerian capital Lagos, a system of walls and ditches built in the XIVth century and located southwest of the town of Ijebu Ode, in Ogun State, southwestern Nigeria. More than 160 km (100 miles) long, these fortifications, some as high as 20 meters (65 feet), consist of a smooth-walled ditch that forms an inner moat in relation to the walls that overhang it. The ditch forms an irregular ring (Map) around the lands of the ancient kingdom of Ijebu. This ring is about 40 km in the north-south direction and 35 km in the east-west direction, which is the equivalent of the Paris périphérique ! Invaded by vegetation, the construction today looks like a green tunnel.

From Ife to the Kingdom of Benin

In the XIVth century, Ife experienced a demographic collapse, characterized by the abandonment of certain enclosures and a strong advance of the forest into formerly residential areas. There was also a break in the transmission of know-how and artisan techniques.

This demographic collapse has been explained as the result of a Black Plague, according to some authors, who draw a parallel with the pandemic waves hitting Europe at the same period.

Part of the inhabitants of Ife were able to take refuge and bring their know-how in metallurgy to the Kingdom of Benin, which lasted for seven hundred years, from the XIIth century until its invasion by the British Empire at the end of the XIXth century. Benin was a coastal West African city-state dominated by the Edos, an ethnic group whose dynasty still survives today.

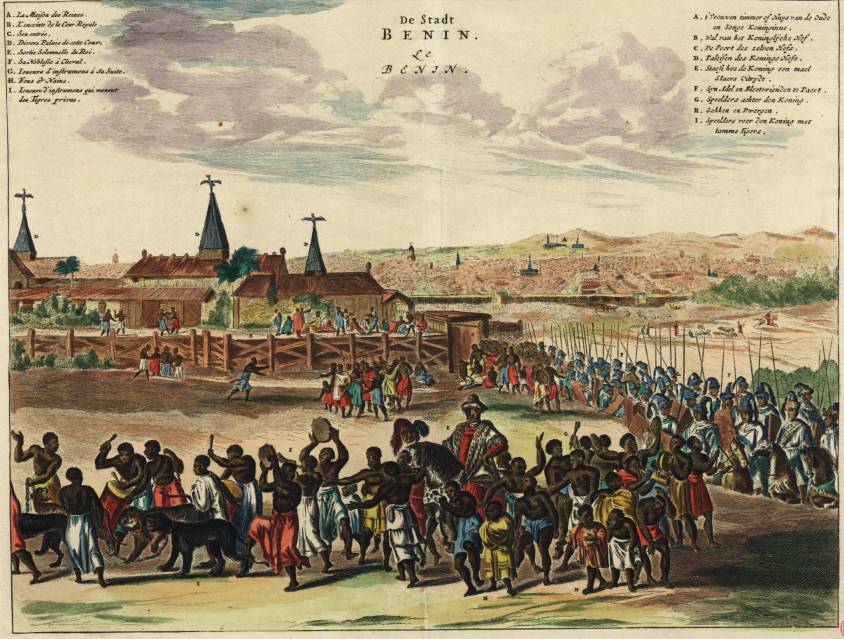

Its territory covers to present-day Benin, plus part of Togo and southwestern Nigeria, where today « Benin City », a historic port on the Benin River, is located. In the heart of the city, the royal residence with monumental proportions translated visually the importance given to political, spiritual and traditional power.

Benin City, a marvel

The social organization of the city impressed European visitors at the end of the XVth century. As a major regional economic trading pole, Benin was full of ivory, pepper and slaves. Benin offered the Europeans palm oil (the oil palm growing abundantly in the region). In exchange, they requested, and obtained guns, allowing the modernization of the Beninese armament.

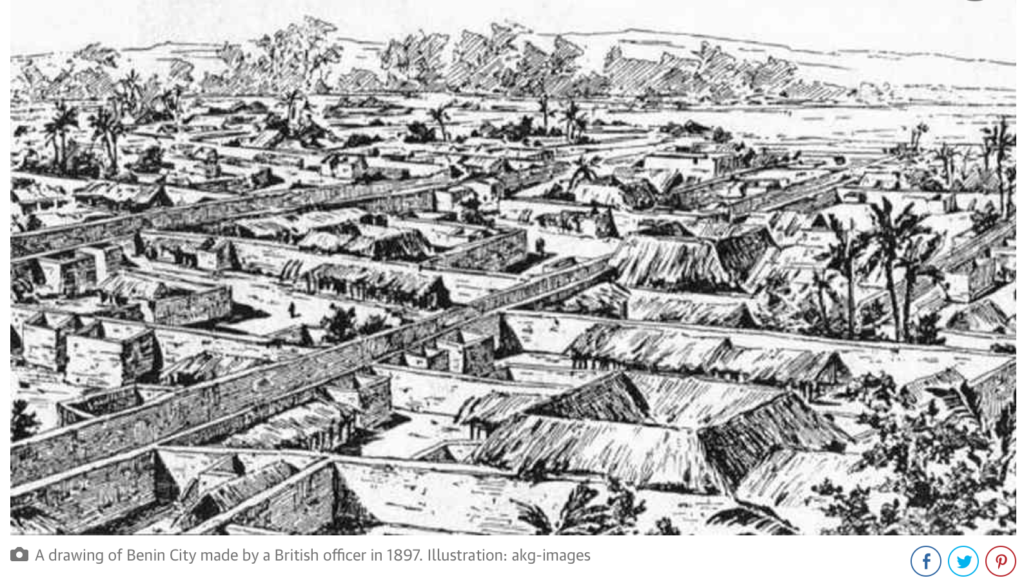

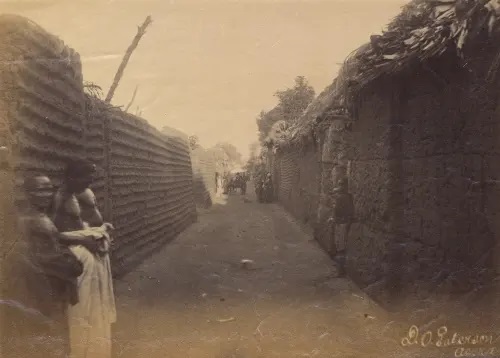

Located in a plain, Benin City is surrounded by massive walls to the south and deep ditches to the north. Beyond the city walls, many other walls have been erected that organize the entire region of the capital into some 500 separate boroughs.

In 2016, an article published by The Guardian recounted the lost splendor of the city. The paper reported:

“The Guinness Book of Records (1974 edition) described the walls of Benin City and its surrounding kingdom as the world’s largest earthworks carried out prior to the mechanical era. According to estimates by the New Scientist’s Fred Pearce, Benin City’s walls were at one point “four times longer than the Great Wall of China, and consumed a hundred times more material than the Great Pyramid of Cheops”.

Pearce writes that these walls “extended for some 16,000 km in all, in a mosaic of more than 500 interconnected settlement boundaries. They covered 6,500 sq km and were all dug by the Edo people … They took an estimated 150 million hours of digging to construct, and are perhaps the largest single archaeological phenomenon on the planet”.

Benin City was also one of the first cities to have a semblance of street lighting. Huge metal lamps, many feet high, were built and placed around the city, especially near the king’s palace. Fueled by palm oil, their burning wicks were lit at night to provide illumination for traffic to and from the palace.

When the Portuguese first “discovered” the city in 1485, they were stunned to find this vast kingdom made of hundreds of interlocked cities and villages in the middle of the African jungle.

In 1691, the Portuguese ship captain Lourenco Pinto observed:

“Great Benin, where the king resides, is larger than Lisbon; all the streets run straight and as far as the eye can see. The houses are large, especially that of the king, which is richly decorated and has fine columns. The city is wealthy and industrious. It is so well governed that theft is unknown and the people live in such security that they have no doors to their houses.”

In contrast, London at the same time is described by Bruce Holsinger, professor of English at the University of Virginia, as being a city of “thievery, prostitution, murder, bribery and a thriving black market made the medieval city ripe for exploitation by those with a skill for the quick blade or picking a pocket”.

African fractals

Benin City’s planning and design was done according to careful rules of symmetry, proportionality and repetition now known as fractal design. The mathematician Ron Eglash, author of African Fractals – which examines the patterns underpinning architecture, art and design in many parts of Africa – notes that the city and its surrounding villages were purposely laid out to form perfect fractals, with similar shapes repeated in the rooms of each house, and the house itself, and the clusters of houses in the village in mathematically predictable patterns.

As he puts it:

“When Europeans first came to Africa, they considered the architecture very disorganized and thus primitive. It never occurred to them that the Africans might have been using a form of mathematics that they hadn’t even discovered yet.”

At the center of the city stood the king’s court, from which extended 30 very straight, broad streets, each about 120-ft wide. These main streets, which ran at right angles to each other, had underground drainage made of a sunken impluvium with an outlet to carry away storm water. Many narrower side and intersecting streets extended off them. In the middle of the streets were turf on which animals fed.

“Houses are built alongside the streets in good order, the one close to the other,” writes the XVIIth-century Dutch visitor Olfert Dapper. “Adorned with gables and steps … they are usually broad with long galleries inside, especially so in the case of the houses of the nobility, and divided into many rooms which are separated by walls made of red clay, very well erected.”

Dapper adds that wealthy residents kept these walls “as shiny and smooth by washing and rubbing as any wall in Holland can be made with chalk, and they are like mirrors. The upper stores are made of the same sort of clay. Moreover, every house is provided with a well for the supply of fresh water”.

Family houses were divided into three sections: the central part was the husband’s quarters, looking towards the road; to the left the wives’ quarters (oderie), and to the right the young men’s quarters (yekogbe).

Daily street life in Benin City might have consisted of large crowds going though even larger streets, with people colorfully dressed – some in white, others in yellow, blue or green – and the city captains acting as judges to resolve lawsuits, moderating debates in the numerous galleries, and arbitrating petty conflicts in the markets.

The early foreign explorers’ descriptions of Benin City portrayed it as a place free of crime and hunger, with large streets and houses kept clean; a city filled with courteous, honest people, and run by a centralized and highly sophisticated bureaucracy.

The city was split into 11 divisions, each a smaller replication of the king’s court, comprising a sprawling series of compounds containing accommodation, workshops and public buildings – interconnected by innumerable doors and passageways, all richly decorated with the art that made Benin famous. The city was literally covered in it.

The exterior walls of the courts and compounds were decorated with horizontal ridge designs (agben) and clay carvings portraying animals, warriors and other symbols of power – the carvings would create contrasting patterns in the strong sunlight. Natural objects (pebbles or pieces of mica) were also pressed into the wet clay, while in the palaces, pillars were covered with bronze plaques illustrating the victories and deeds of former kings and nobles.

At the height of its greatness in the XIIth century – well before the start of the European Renaissance – the kings and nobles of Benin City patronized craftsmen and lavished them with gifts and wealth, in return for their depiction of the kings’ and dignitaries’ great exploits in intricate bronze sculptures.

“These works from Benin are equal to the very finest examples of European casting technique,” wrote Professor Felix von Luschan, formerly of the Berlin Ethnological Museum. Italian Renaissance artist “Benvenuto Celini could not have cast them better, nor could anyone else before or after him. Technically, these bronzes represent the very highest possible achievement.”

The fatal encounter with « civilization »

Following the Berlin Conference of 1885, where the British, Portuguese, Belgian, German, French, Italian and other European colonial powers shared Africa like a big chocolate cake that they intended to devour, in the name of the immutable laws of the freshly invented science of “geopolitics”, European invasions multiplied and gained in brutality.

Thus, following the king of Benin’s refusal to cede to the British the national monopoly on the production of palm oil and other products, Benin City was looted, burned and reduced to ashes during a British punitive expedition in 1897. The king (the oba) is arrested and forced into exile and thousands of beautiful « bronzes of Benin », though less realistic than those of Ife, are stolen, sold and partly lost.

They end up on the art market and in museums, including the British Museum (700 objects) and the Berlin Museum of Ethnology (500 pieces). The British government itself sells some of them « to cover the cost of the expedition« .

So, while some clearly entered history with their beautiful art, others exited civilization with their barbarian crimes.

Summary bibliography:

- Ifè, une civilisation africaine, Frank Willett, Jardin des Arts/Tallandier, Paris 1971;

- General History of Africa, Présence africaines/Edicef/Unesco, Paris 1987;

- Atlas historique de l’Afrique, Editions du Jaguar, Paris 1988;

- L’Afrique ancienne, de l’Acus au Zimbabwe, under the direction of François-Xavier Fauvelle, Belin/Humensis, Paris 2018.