Étiquette : Pecham

Van Eyck, a Flemish Painter using Arab Optics?

What follows is an edited transcript of a lecture by Karel Vereycken on the subject of “Perspective in XVth-century Flemish religious painting”.

It was delivered at the international colloquium “La recherche du divin à travers l’espace géométrique” (The quest for the divine through geometrical space) at the Paris Sorbonne University on April 26-28, 2006, under the direction of Luc Bergmans, Department of Dutch Studies (Paris IV Sorbonne University).

Introduction

« Perspective in XVth-century Flemish religious painting ». At first glance, this title may seem surprising. While the genius of fifteenth-century Flemish painters is universally attributed to their mastery of drying oil and their intricate sense of detail, their spatial geometry as such is usually identified as the very counter-example of the “right perspective”.

Disdained by Michelangelo and his faithful friend Vasari, the Flemish « primitives » would never have overcome the medieval, archaic and empirical model. For the classical “narritive”, still in force today, stipulates that only « Renaissance » perspective, obeying the canon of « linear », “mathematical” perspective, is the only « right », and the “scientific” one.

According to the same narrative, it was the research carried out around 1415-20 by the Duomo architect Filippo Brunelleschi (1377-1446), superficially mentioned by Antonio Tuccio di Manetti some 60 years later, which supposedly enabled Leon Battista Alberti (1404-1472), proclaiming himself Brunelleschi’s intellectual heir, to invent « perspective ».

In 1435, in De Pictura, a book entirely devoid of graphic illustration, Alberti is said to have formulated the premises of a perspectivist canon capable of representing, or at least conforming to, our modern notions of Cartesian space-time (NOTE 1), a space-time characterized as « entirely rational, i.e. infinite, continuous and homogeneous », « in one word, a purely mathematical space [dixit Panofsky] » (NOTE 2)

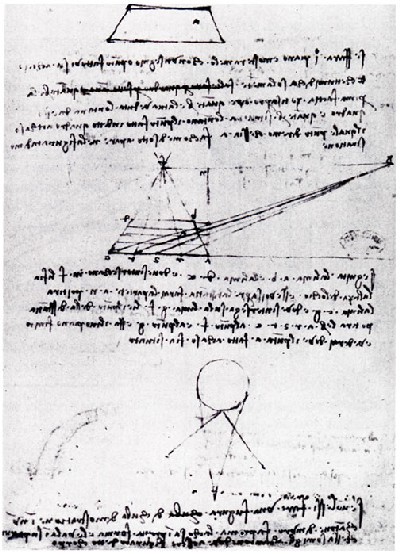

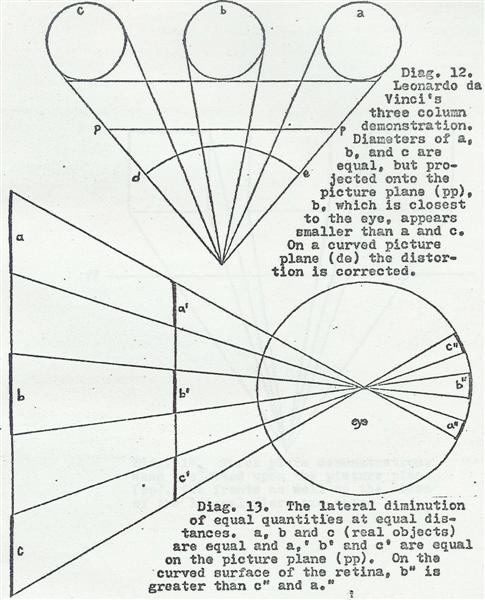

Long afterwards, in a drawing from the Codex Madrid, Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1519) attempted to unravel the workings of this model.

But in the same manuscript, he rigorously demonstrated the inherent limitations of the Albertian Renaissance perspectivist canon.

The drawing on f°15, v° clearly shows that the simple projection of visual pyramid cross-sections on a plane paradoxically causes their size to increase the further they are from the point of vision, whereas reality would require exactly the opposite. (NOTE 3)

With this in mind, Leonardo began to question the mobility of the eye and the curvilinear nature of the retina. Refusing to immobilize the viewer on an exclusive point of vision (NOTE 4), Leonardo used curvilinear constructions to correct these lateral deformations. (NOTE 5) In France, Jean Fouquet and others worked along the same lines.

But Leonardo’s powerful arguments were ignored, and he was unable to prevent this rewriting of history.

Despite this official version of art history, it should be noted that at the time, Flemish painters were elevated to pinnacles by Italy’s greatest patrons and art connoisseurs, specifically for their ability to represent space.

Bartolomeo Fazio, around the middle of the 15th century, observed that the paintings of Jan van Eyck, an artist billed as the « principal painter of our time », showed « tiny figures of men, mountains, groves, villages and castles rendered with such skill that one would think them fifty thousand paces apart. » (NOTE 6)

Such was their reputation that some of the great names in Italian painting had no qualms about reproducing Flemish works identically. I’m thinking, for example, of the copy of Hans Memlinc‘s Christ Crowned with Thorns at the Genoa Museum, copied by Domenico Ghirlandajo (Philadelphia Museum).

But post-Michelangelo classicism deemed the non-conformity of Flemish spatial geometry with Descartes’ « extended substance » to be an unforgivable crime, and any deviation from, or insubordination to, the « Renaissance » perspectivist canon relegated them to the category of « primitives », i.e. « empiricists », clearly devoid of any scientific culture.

Today, ironically, it is almost exclusively those artists who explicitly renounce all forms of perspectivist construction in favor of pseudo-naïveté, who earn the label of modernity…

In any case, current prejudices mean that 15th-century Flemish painting is still accused of having ignored perspective.

It’s true, however, that at the end of the XIVth century, certain paintings by Melchior Broederlam (c. 1355-1411) and others by Robert Campin (1375-1444) (Master of Flémalle) show the viewer interiors where plates and cutlery on tables threaten to suddenly slide to the floor.

Nevertheless, it must be admitted that whenever the artist « ignores » or disregards the linear perspective scheme, he seems to do so more by choice than by incapacity. To achieve a limpid composition, the painter prioritizes his didactic mission to the detriment of all other considerations.

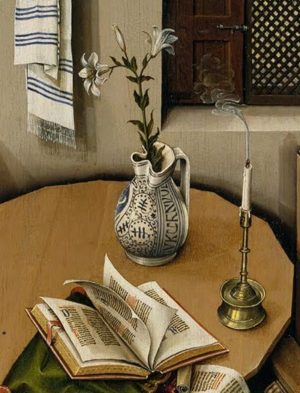

For example, in Campin’s Mérode Altarpiece, the exaggerated perspective of the table clearly shows that the vase is behind the candlestick and book.

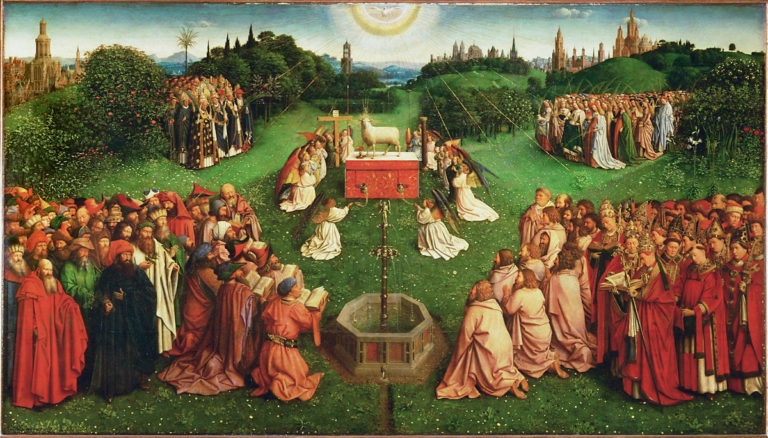

Jan van Eyck’s Lam Gods (Mystic Lamb) in Ghent is another example.

Never could so many figures, with so much detail and presence, be shown with a linear perspective where the figures in the foreground would hide those behind. (NOTE 7)

But the intention to approximate a credible sense of space and depth remains.

If this perspective seems flawed by its linear geometry, Campin imposes an extraordinary sense of space through his revolutionary treatment of shadows. As every painter knows, light is painted by painting shadow.

In Campin’s work, every object and figure is exposed to several sources of light, generating a darker central shadow as the fruit of crossed shadows.

Van Eyck influenced by Arab Optics?

Roger Bacon, statue in Oxord.

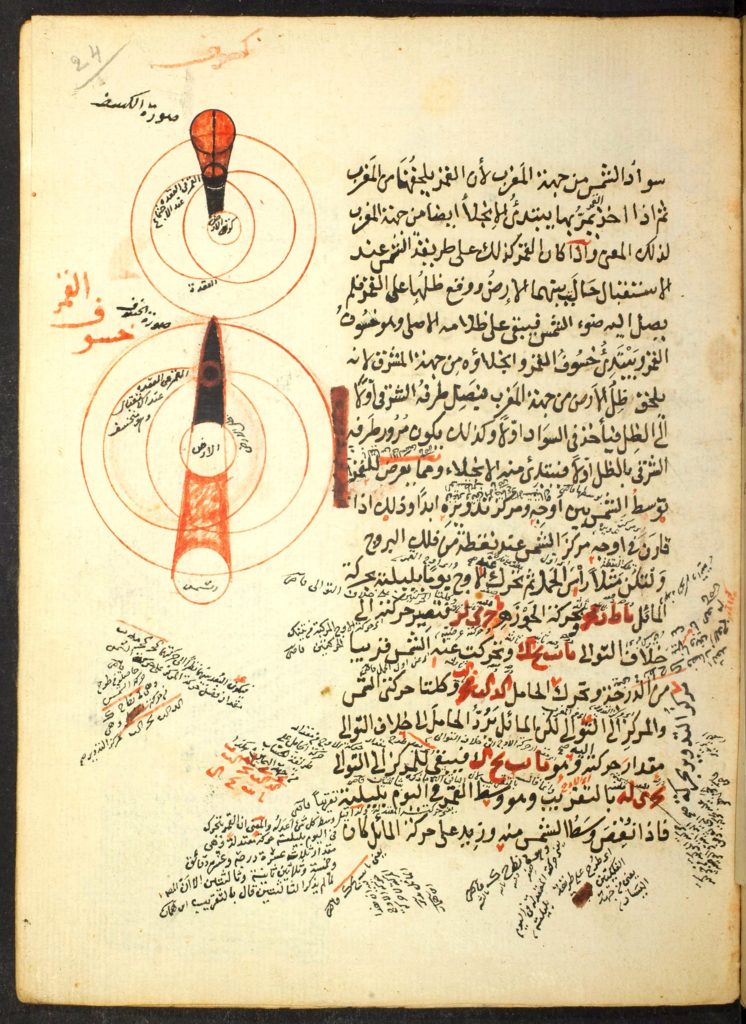

This new treatment of light-space has been largely ignored. However, there are several indications that this new conception was partly the result of the influence of « Arab » science, in particular its work on optics.

Translated into Latin and studied from the XIIth century onwards, their work was developed in particular by a network of Franciscans whose epicenter was in Oxford (Robert Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, etc.) and whose influence spread to Chartres, Paris, Cologne and the rest of Europe.

It should be noted that Jan van Eyck (1395-1441), an emblematic figure of Flemish painting, was ambassador to Paris, Prague, Portugal and England.

I’ll briefly mention three elements that support this hypothesis of the influence of Arab science.

Curved mirrors

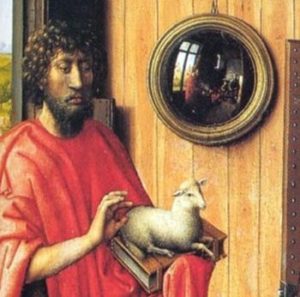

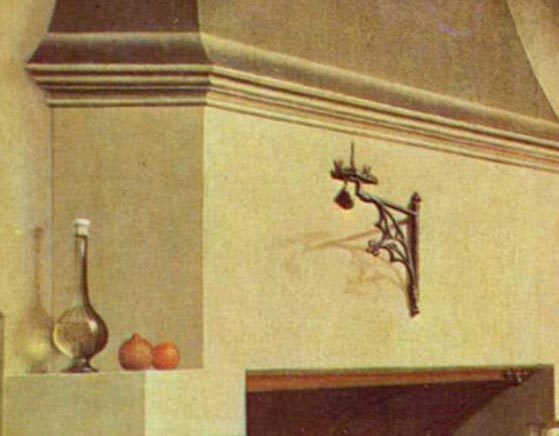

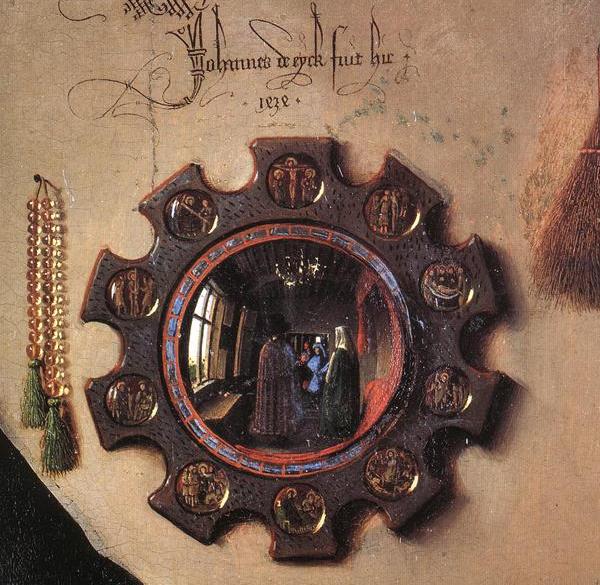

Robert Campin (master of Flémalle) in the Werl Triptych (1438) and Jan van Eyck in the Arnolfini portrait (1434), each feature convex mirrors of considerable size.

It is now certain that glaziers and mirror-makers were full members of the Saint Luc guild, the painters’ guild. (NOTE 8)

But it is relevant to know that Campin, now recognized as having run the workshop in Tournai where the painters Van der Weyden and Jacques Daret were trained, produced paintings for the Franciscans in this city. Heinrich Werl, who commissioned the altarpiece featuring the convex mirror, was an eminent Franciscan theologian who taught at the University of Cologne.

Artistic representation of Ibn Al-Haytam (Alhazen)

These convex and concave (or ardent) mirrors were much studied during the Arab renaissance of the IXth to XIth centuries, in particular by the Arab philosopher Al-Kindi (801-873) in Baghdad at the time of Charlemagne.

Arab scientists were not only in possession of the main body of Hellenic work on optics (Euclid‘s Optics, Ptolemy‘s Optics, the works of Heron of Alexandria, Anthemius of Tralles, etc.), but it was sometimes the rigorous refutation of this heritage that was to give science its wings.

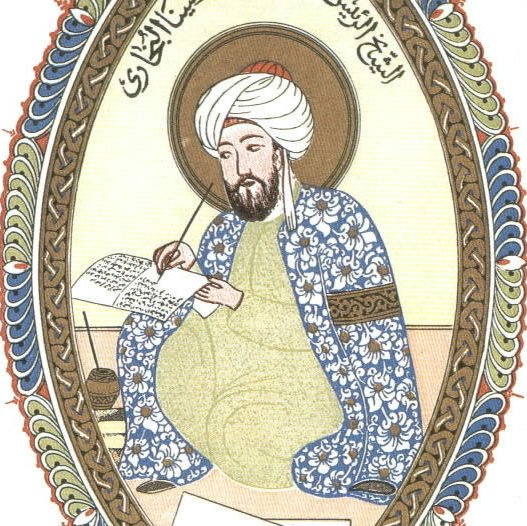

After the decisive work of Ibn Sahl (Xth century), it was that of Ibn Al-Haytam (Latin name : Alhazen) (NOTE 9) on the nature of light, lenses and spherical mirrors that was to have a major influence. (NOTE 10)

As mentioned above, these studies were taken up by the Oxford Franciscans, starting with the English bishop of Lincoln, Robert Grosseteste (1168-1253).

In De Natura Locorum, for example, Grosseteste shows a diagram of the refraction of light in a spherical glass filled with water. And in his De Iride he marvels at this science which he connexts to perspective :

« This part of optics, so well understood, shows us how to make very distant things appear as if they were situated very near, and how we can make small things situated at a distance appear to the size we desire, so that it becomes possible for us to read the smallest letters from incredible distances, or to count sand, or grains, or any small object.«

Grosseteste’s pupil Roger Bacon (1212-1292) wrote De Speculis Comburentibus, a specific treatise on « Ardent Mirrors » which elaborates on Ibn Al-Haytam‘s work.

Flemish painters Campin, Van Eyck and Van der Weyden proudly display their knowledge of this new scientific and technological revolution metamorphosed into Christian symbolisms.

Their paintings feature not only curved mirrors but also glass bottles, which they use as a metaphor for the immaculate conception.

A Nativity hymn of that period says:

« As through glass the ray passed without breaking it, so of the Virgin Mother, Virgin she was and virgin she remained… » (NOTE 11)

The Treatment of Light

In his Discourse on Light, Ibn Al-Haytam develops his theory of light propagation in extremely poetic language, setting out requirements that remind us of the « Eyckian revolution ». Indeed, Flemish « realism » and perspective are the result of a new treatment of light and color.

Ibn Al-Haytam:

« The light emitted by a luminous body by itself -substantial light- and the light emitted by an illuminated body -accidental light- propagate on the bodies surrounding them. Opaque bodies can be illuminated and then in turn emit light. »

This physical principle, theorized by Leonardo da Vinci, is omnipresent in Flemish painting. Just look at the images reflected in the helmet of St. George in Van Eyck‘s Madonna to Canon van der Paele (NOTE 12).

In each curved surface of Saint George’s helmet, we can identify the reflection of the Virgin and even a window through which light enters the painting.

The shining shield on St. George’s back reflects the base of the adjacent column, and the painter’s portrait appears as a signature. Only a knowledge of the optics of curved surfaces can explain this rendering.

Ibn Al-Haytam:

« Light can penetrate transparent bodies: water, air, crystal and their counterparts. »

And :

« Transparent bodies have, like opaque bodies, a ‘receiving power’ for light, but transparent bodies also have a ‘transmitting power’ for light.«

Isn’t the development of oil mediums and glazes by the Flemish an echo of this research? Alternating opaque and translucent layers on very smooth panels, the specificity of the oil medium alters the angle of light refraction.

In 1559, the painter-poet Lucas d’Heere referred to van Eyck‘s paintings as « mirrors, not painted scenes.«

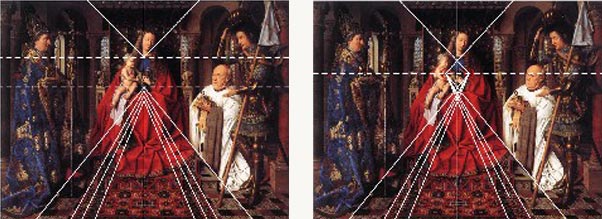

Binocular perspective

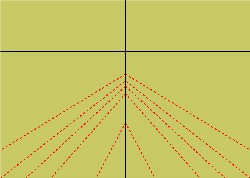

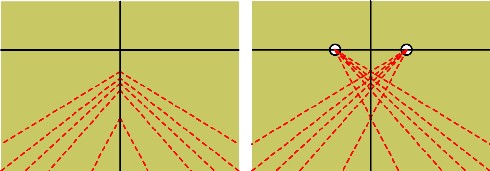

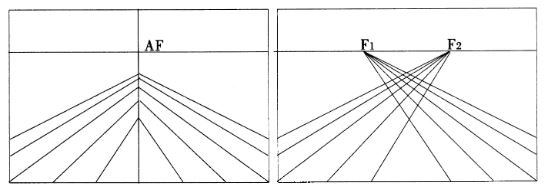

Before the advent of « right » central linear perspective, art historians sought a coherent explanation for its birth in the presence of several seemingly disparate vanishing points by theorizing a so-called central « fishbone » perspective.

In this model, a number of vanishing lines, instead of coinciding in a single central vanishing point on the horizon, either end up in a « vanishing region » (NOTE 13), or align with what some call a vertical « vanishing axis », forming a kind of « fishbone ».

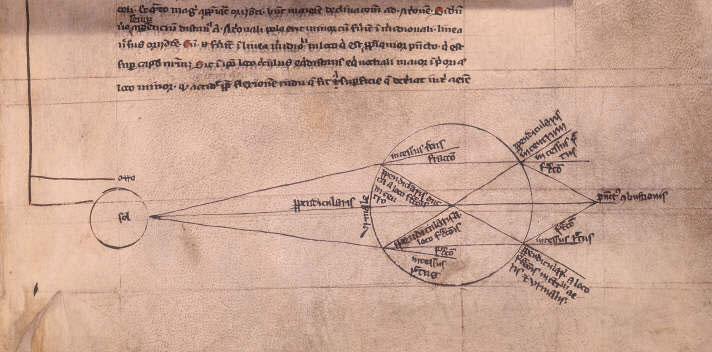

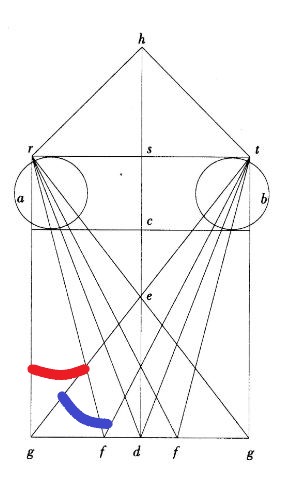

French Professor Dominique Raynaud, who worked for years on this issue, underscores that « all medieval treatises on perspective address the question of binocular vision », notably the Polish scholar Witelo (1230-1280) (NOTE 15) in his Perspectiva (I,27), an insight he also got from the works of Ibn Al-Haytam.

Witelo presents a figure to defend the idea that

« the two forms, which penetrate two homologous points of the surface of the two eyes, arrive at the same point of the concavity of the common nerve, and are superimposed at this point to become one » (Perspectiva, III, 37).

A similar line of reasoning can be found in Roger Bacon‘s Perspectiva Communis, written by John Pecham, Archbishop of Canterbury (1240-1290) for whom:

« the duality of the eyes must be reduced to unity »

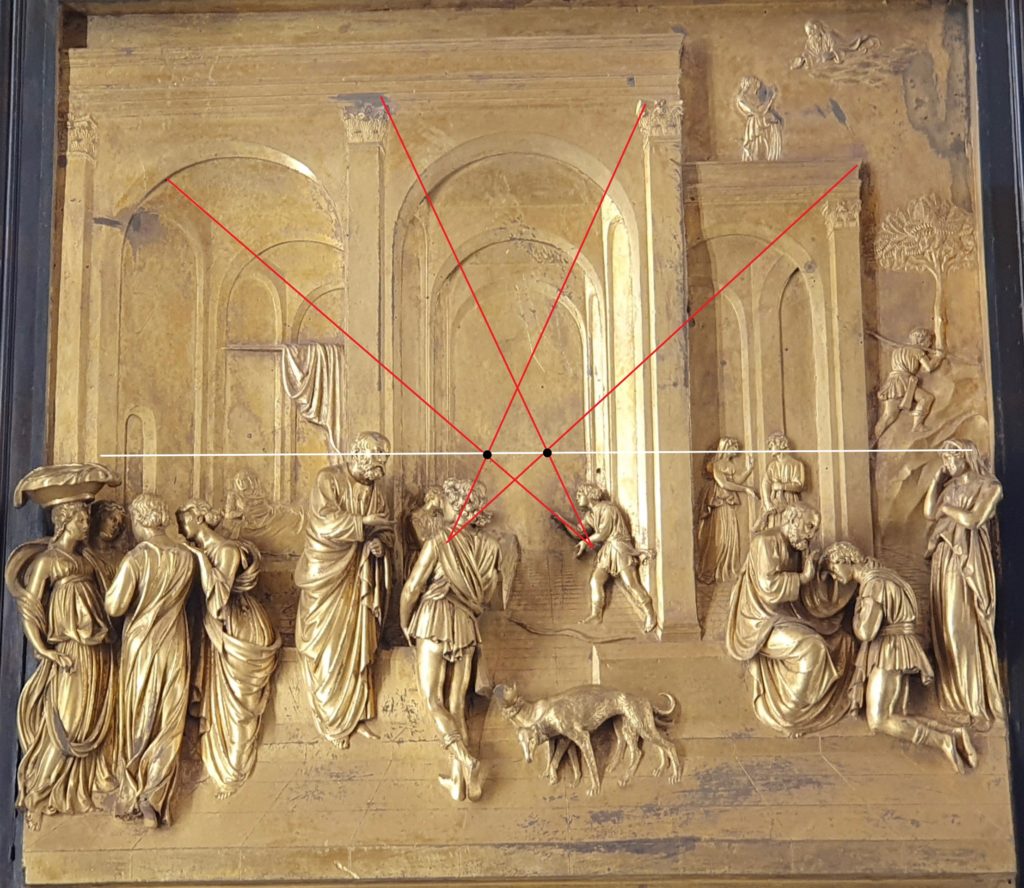

So, as Professor Raynaud proposed, if we extend the famous vanishing lines (i.e., in our case, the « fish bones ») until they intersect, the « vanishing axis » problem disappears, as the vanishing lines meet. Interestingly, the result is a perspective with two vanishing points in the central region!

Suddenly, the diagrams drawn up to demonstrate the « empiricism » of the Flemish painters, if viewed from this point of view, reveal a legitimate construction probably based on optics as transmitted by Arab science and rediscovered by Franciscan networks and others.

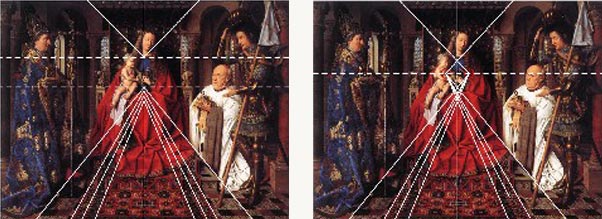

Two paintings by Jan van Eyck clearly demonstrate that he followed this approach: The Madonna with Canon van der Paele of 1436 and the Dresden Tryptic of 1437.

What seemed a clumsy, empirical approach in the form of a « fishbone » perspective (left) turns out to be a binocular perspective construction.

Was this type of perspective specifically Flemish?

A close examination of works by Ghiberti, Donatello and Paolo Uccello, generally dating from the first half of the XVth Century, reveals a mastery of the same principle.

Cusanus

But this whole demonstration is merely a look into the past through the eyes of modern scientific rationality. It would be a grave error not to take into account the immense influence of the Rhenish (Master Eckhart, Johannes Tauler, Heinrich Suso) and Flemish (Hadewijch of Antwerp, Jan van Ruusbroec, etc.) « mystics ».

This trend began to flourish again with the rediscovery of the Christianized neo-Platonism of Dionysius the Areopagite (Vth-VIth century), made accessible… by the new translations of the Franciscan Grosseteste in Oxford.

The spiritual vision of the Aeropagite, expressed in a powerful imagery language, is directly reminiscent of the metaphorical approach of the Flemish painters, for whom a certain type of light is simply the revelation of divine grace.

In On the Heavenly Hierarchy, Dionysius immediately presents light as a manifestation of divine goodness. It ennobles us and enables us to enlighten others:

« Let those who are illuminated be filled with divine clarity, and the eyes of their understanding trained to the work of chaste contemplation; finally, let those who are perfected, once their primitive imperfection has been abolished, share in the sanctifying science of the marvelous teachings that have already been manifested to them; similarly, let the purifier excel in the purity he communicates to others; let the illuminator, gifted with a greater penetration of spirit, equally fit to receive and transmit light, happily flooded with sacred splendor, pour it out in pressing streams on those who are worthy… » [Chap. III, 3]

Let’s think again of the St. George in Van Eyck‘s Madonna to Canon van der Paele, which indeed pours forth the multiple images of the Virgin who enlightens him.

This theo-philosophical trend reached full maturity in the work of Cardinal Nicolas of Cusa (Cusanus) (1401-1464) (NOTE 16), embodying the extremely fruitful encounter of this « negative theology » with Greek science, Socratic knowledge and Christian Humanism.

In contrast to both a science « without a hypothesis of God » and a metaphysics with an esoteric drift, an agapic love leads it to the education of the greatest number, to the defense of the weak and the humiliated.

The Brothers and Sisters of the Common Life, educating Erasmus of Rotterdam and inspiring Cusanus, are the best example of this.

But let’s sketch out some of Cusanus’ key ideas on painting.

In De Icona (The Vision of God) (1453), which he sent to the Benedictine monks of the Tegernsee, Cusanus condenses his fundamental work On Learned Ignorance (1440), in which he develops the concept of the coincidence of opposites. His starting point was a self-portrait of his friend « Roger », the Flemish painter Rogier van der Weyden, which he sent together with his sermon to the monks.

This self-portrait, like the multiple faces of Christ painted in the XVth century, uses an « optical illusion » to create the effect of a gaze that fixes the viewer, regardless of his or her position in front of the altarpiece.

In De Icona, written as a sermon, Cusanus asks monks to stand in a semicircle around the painting and watch this gaze pursue them as they move along the segment of the curve. In fact, he elaborates a pedagogical paradox based on the fact that the Greek name for God, Theos, has its etymological origin in the verb theastai (to see, to look at).

As you can see, he says, God looks at you personally, and his gaze follows you everywhere. He is therefore one and many. And even when you turn away from him, his gaze falls on you. So, miraculously, although he looks at everyone at the same time, he nevertheless establishes a personal relationship with each one. If « seeing » for God is « loving », God’s point of vision is infinite, omniscient and omnipotent love.

A parallel can be drawn here with the spherical mirror at the center of Jan van Eyck’s painting The Arnolfini portrait, painted in 1434, nineteen years before this sermon.

Firstly, this circular mirror is surrounded by the ten stations of Christ’s Passion, juxtaposed by a rosary, an explicit reference to God.

Secondly, it reveals a view of the entire room, an image that completely escapes the linear perspective of the foreground. A view comparable to the allcompassing « Vision of God » developed by Cusanus.

Finally, we see two figures in the mirror, but not the image of the painter behind his easel. These are undoubtedly the two witnesses to the wedding. Instead of signing his painting with « Van Eyck invent. », the painter signed his painting above the mirror with « Van Eyck was here » (NOTE 17), identifying himself as a witness.

As Dionysius the Aeropagite asserted:

« [the celestial hierarchy] transforms its adepts into so many images of God: pure and splendid mirrors where the eternal and ineffable light can shine, and which, according to the desired order, reflect liberally on inferior things this borrowed brightness with which they shine. » [Chap. III, 2]

The Flemish mystic Jan van Ruusbroec (1293-1381) evokes a very similar image in his Spiegel der eeuwigher salicheit (Mirror of eternal salvation) when he says:

« Ende Hi heeft ieghewelcs mensche ziele gescapen alse eenen levenden spieghel, daer Hi dat Beelde sijnre natueren in gedruct heeft. » (And he created each human soul as a living mirror, in which he imprinted the image of his nature).

And so, like a polished mirror, Van Eyck’s soul, illuminated and living in God’s truth, acts as an illuminating witness to this union. (NOTE 18)

So, although the Flemish painters of the XVth century clearly had a solid scientific foundation, they choose such or such perspective depending on the idea they wanted to convey.

In essence, their paintings remain objects of theo-philosophical speculation or as you like « intellectual prayer », capable of praising the goodness, beauty and magnificence of a Creator who created them in His own image. By the very nature of their approach, their interest lay above all in the geometry of a kind of « paradoxical space-light » capable, through enigma, of opening us up to a participatory transcendence, rather than simply seeking to « represent » a dead space existing outside metaphysical reality.

The only geometry worthy of interest was that which showed itself capable of articulating this non-linearity, a « divine » or « mystical » perspective capable of linking the infinite beauty of our commensurable microcosm with the immeasurable goodness of the macrocosm.

Thank you,

NOTES:

- Recently, Italian scholars have pointed to the role of Biagio Pelacani Da Parma (d. 1416), a professor at the University of Padua near Venice, in imposing such a perspective, which privileged only the « geometrical laws of the act of vision and the rules of mathematical calculation ».

- Erwin Panofsky, Perspective as Symbolic Form, p.41-42, Les Éditions de Minuit, Paris, 1975.

- Institut de France, Manuscrit E, 16 v° « the eye [h] perceives on the plane wall the images of distant objects greater than that of the nearer object. »

- Leonardo understands that Albertian perspective, like anamorphosis, condemns the viewer to a single, immobile point of vision.

- See, for example, the slight enlargement of the apostles at the ends of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper in the Milan refectory.

- Baxandall, Bartholomaeus Facius on painting, Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 27, (1964). Fazio is also enthusiastic about a world map (now lost) by Jan van Eyck, in which all the places and regions of the earth are depicted recognizably and at measurable distances.

- To escape this fate, Pieter Bruegel the Elder used a cavalier perspective, placing his horizon line high up.

- Lionel Simonot, Etude expérimentale et modélisation de la diffusion de la lumière dans une couche de peinture colorée et translucide. Application à l’effet visuel des glacis et des vernis, p.9 (PhD thesis, Nov. 2002).

- Ibn Al-Haytam (Alhazen) (965-1039) wrote some 200 works on mathematics, astronomy, physics, medicine and philosophy. Born in Basra, after working on the development of the Nile in Egypt, he travelled to Spain. He is said to have carried out a series of highly detailed experiments on theoretical and experimental optics, including the camera obscura (darkroom), work that was later to feature in Leonardo da Vinci’s studies. Da Vinci may well have read the lengthy passages by Alhazen that appear in the Commentari of the Florentine sculptor Ghiberti. According to Gerbert d’Aurillac (the future Pope Sylvester II in 999), Bishop of Rheims, brought back from Spain the decimal system with its zero and an astrolabe, it was thanks to Gerard of Cremona (1114-c. 1187) that Europe gained access to Greek, Jewish and Arabic science. This scholar went to Toledo in 1175 to learn Arabic, and translated some 80 scientific works from Arabic into Latin, including Ptolemy’s Almagest, Apollonius’ Conics, several treatises by Aristotle, Avicenna‘s Canon, and the works of Ibn Al-Haytam, Al-Kindi, Thabit ibn Qurra and Al-Razi.

- In the Arab world, this research was taken up a century later by the Persian physicist Al-Farisi (1267-1319). He wrote an important commentary on Alhazen’s Treatise on Optics. Using a drop of water as a model, and based on Alhazen’s theory of double refraction in a sphere, he gave the first correct explanation of the rainbow. He even suggested the wave-like property of light, whereas Alhazen had studied light using solid balls in his reflection and refraction experiments. The question was now: does light propagate by undulation or by particle transport?

- Meiss, M., Light as form and symbol in some fifteenth century paintings, Art Bulletin, XVIII, 1936, p. 434.

- Note also the fact that the canon shows a pair of glasses…

- Brion-Guerry in Jean Pèlerin Viator, sa place dans l’histoire de la perspective, Belles Lettres, 1962, p. 94-96, states in obscure language that « the object of representation behaves most often in Van Eyck as a cubic volume seen from the front and from the inside. Perspectival foreshortening is achieved by constructing a rectangle whose sides form the base of four trapezoids. The orthogonals thus tend towards four distinct points of convergence, forming a ‘vanishing region' ».

- Dominique Raynaud, L’Hypothèse d’Oxford, essai sur les origines de la perpective, PUF, Paris 1998.

- Witelo was a friend of the Flemish Dominican scholar Willem van Moerbeke, a translator of Archimedes in contact with Saint Thomas Aquinas. Moerbeke was also in contact with the mathematician Jean Campanus and the Flemish neo-Platonic astronomer Hendrik Bate van Mechelen. Johannes Kepler‘s own work on human vision builds on that of Witelo.

- Cusanus was above all a man of science and theology. But he was also a political organizer. The painter Jan van Eyck fought for the same goals, as evidenced by the ecumenical theme of the Ghent polyptych. It shows the Mystic Lamb, symbolizing the sacrifice of the Son of God for the redemption of mankind, capable of reuniting a church torn apart by internal differences. Hence the presence of the three popes in the central panel, here united before the lamb. Van Eyck also painted a portrait of Cardinal Niccolo Albergati, one of the instigators of the great Ecumenical Council organized by Cusanus in Ferrara and then moved to Florence. If Cusanus called Van der Weyden « his friend Roger », it is also thought that Robert Campin may have met him, since he would have attended the Council of Basel, as did one of his commissioners, the Franciscan theologian Heinrich Werl.

- Jan Van Eyck was one of the first painters in the history of art to date and sign his paintings with his own name.

- Myriam Greilsammer’s book L’Envers du tableau, Mariage et Maternité en Flandre Médiévale (Editions Armand Colin, 1990) documents Arnolfini’s sexual escapades. Arnolfini was taken to court by one of his victims, a female servant. Van Eyck seems to have understood that the knightly Arnoult Fin, Lucchese financier and commercial representative of the House of Medici in Bruges, required the somewhat peculiar presence of the eye of the lord.

Avicenna and Ghiberti’s role in the invention of perspective during the Renaissance

By Karel Vereycken, Paris, France.

Same article in FR, même article en FR.

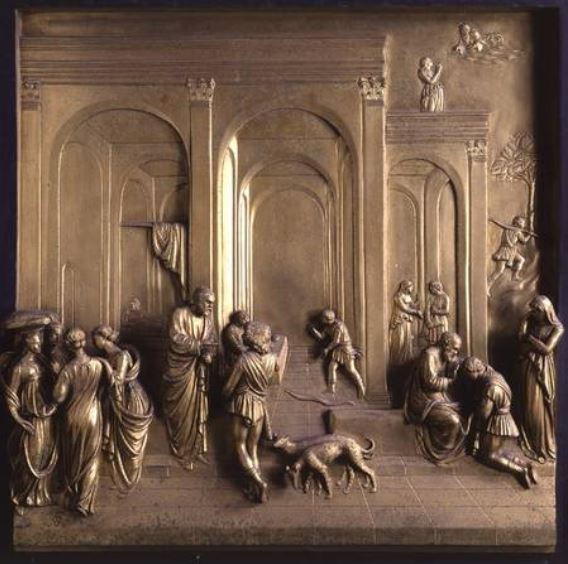

No visitor to Florence can miss the gilded bronze reliefs decorating the Porta del Paradiso (Gates of Paradise), the main gate of the Baptistery of Florence right in front of the Cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore surmounted by Filippo Brunelleschi’s splendid cupola.

In this article, Karel Vereycken sheds new light on the contribution of Arab science and Ghiberti’s crucial role in giving birth to the Renaissance.

Historical context

The Baptistery, erected on what most Florentines thought to be the site of a Roman temple dedicated to the Roman God of Mars, is one of the oldest buildings in the city, constructed between 1059 and 1128 in the Florentine Romanesque style. The Italian poet Dante Alighieri and many other notable Renaissance figures, including members of the Medici family, were baptized in this baptistery.

During the Renaissance, in Florence, corporations and guilds competed for the leading role in design and construction of great projects with illustrious artistic creations.

While the Arte dei Lana (corporation of wool producers) financed the Works (Opera) of the Duomo and the construction of its cupola, the Arte dei Mercantoni di Calimala (the guild of merchants dealing in buying foreign cloth for finishing and export), took care of the Baptistery and financed the embellishment of its doors.

The Gates of Paradise

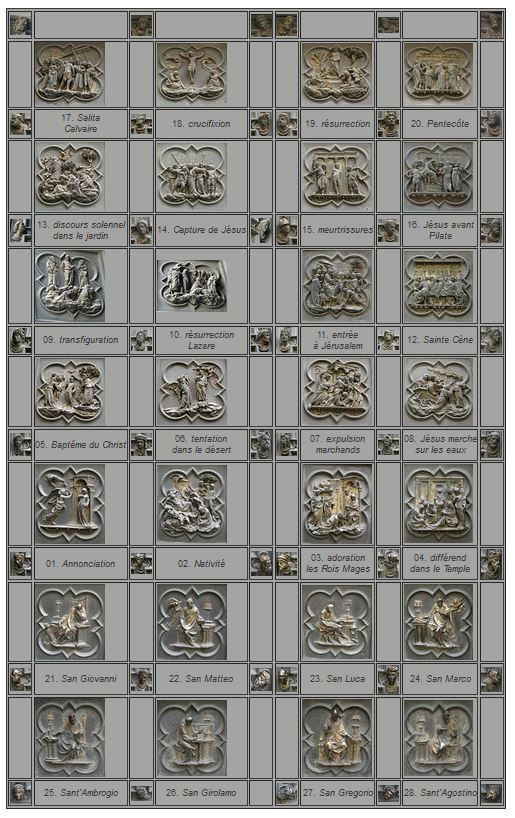

The Baptistry, an octagonal building, has four entrances (East, West, North and South) of which only three (South, North and East) have sets of artistically important bronze doors with relief sculptures. Three dates are key : 1329, 1401 and 1424.

- In 1329, the Calimala Guild, on Giotto‘s recommendation, ordered Andrea Pisano (1290-1348) to decorate a first set of doors (initialy installed as the East doors, i.e. seen when one leaves the Cathedral, but today South). These consist of 28 quatrefoil (clover-shaped) panels, with the 20 top panels depicting scenes from the life of St. John the Baptist (the patron of the edifice). The 8 lower panels depict the eight virtues of hope, faith, charity, humility, fortitude, temperance, justice, and prudence, praised by Plato in his Republic and represented during the XVIth century by the Flemish humanist painter and reader of Petrarch, Peter Brueghel the Elder. Construction took 8 years, from 1330 till 1338.

- In 1401, after having narrowly won the competition with Brunelleschi, the 23 year old and inexperienced young goldsmith Lorenzo Ghiberti (1378-1455), is commissioned by the Calima Guild to decorate the doors which are today the North Gate. Ghiberti cast the bronze high reliefs using a method known as lost-wax casting, a technique that he had to reinvent entirely since it was lost since the fall of the Roman Empire. One of the reasons Ghiberti won the contest, was that his technique was so advanced that it required 20 % less (7 kg per panel) bronze than that of his competitors, bronze being a dense material far more costly than marble. His technique, applied to the entire decoration of the North Gate, as compared to his competitors, would save some estimated 100 kg of bronze. And since in 1401, with the plague regularly hitting Florence, economic conditions were poor, even the wealthy Calimala took into account the total costs of the program.

The bronze doors are comprised of 28 panels, with 20 panels depicting the life of Christ from the New Testament. The 8 lower panels show the four Evangelists and the Church Fathers Saint Ambrose, Saint Jerome, Saint Gregory, and Saint Augustine. The construction took 24 years.

- In 1424, Ghiberti, at age 46, was given—unusually, with no competition—the task of also creating the East Gate. Only in 1452 did Ghiberti, then seventy-four years old, install the last bronze panels, since construction lasted this time 27 years! According to Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574), Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475-1564) later judged them « so beautiful they would grace the entrance to Paradise ».

Over two generations, a bevy of well paid assistants and pupils were trained by Ghiberti, including exceptional artists, such as Luca della Robbia, Donatello, Michelozzo, Benozzo Gozzoli, Bernardo Cennini, Paolo Uccello, Andrea del Verrocchio and Ghiberti’s sons, Vittore and Tommaso. And over time, the seventeen-foot-tall, three-ton bronze doors became an icon of the Renaissance, one of the most famous works of art in the world.

In 1880, the French sculptor Auguste Rodin was inspired by it for his own Gates of Hell on which he worked for 38 year

Revolution

Of utmost interest for our discussion here is the dramatic shift in conception and design of the bronze relief sculptures that occurred between the North and the East Gates, because it reflects how bot the artist as well as his patrons used the occasion to share with the broader public their newest ideas, inventions and exciting discoveries.

The themes of the North Gate of 1401 were inspired by scenes from the New Testament, except for the panel made by Ghiberti, « The Sacrifice of Isaac », which had won him the selection competition the same year. To complete the ensemble, it was therefore only logical that the East Gate of 1424 would take up the themes of the Old Testament.

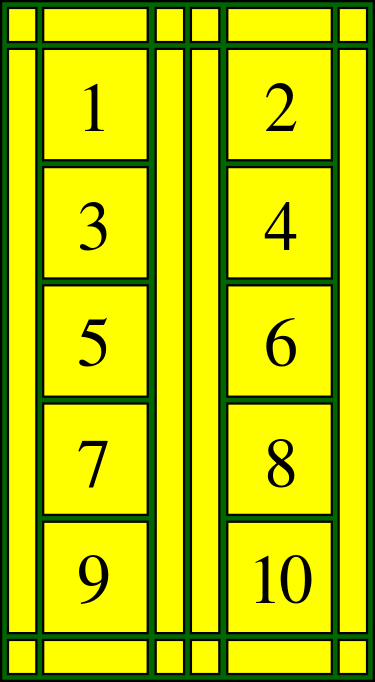

Originally, it was the scholar and former chancellor of Florence Leonardo Bruni (1369-1444) who planned an iconography quite similar to the two previous doors. But, after heated discussions, his proposal was rejected for something radically new. Instead of realizing 28 panels, it was decided, for aesthetic reasons, to reduce the number of panels to only 10 much larger square reliefs, between borders containing statuettes in niches and medallions with busts.

Hence, since each of the 10 chapters of the Old Testament contains several events, the total number of scenes illustrated, within the 10 panels has risen to 37 and all appear in perspective :

- Adam and Eve (The Creation of Man)

- Cain and Abel (Jalousie is the origin of Sin)

- Noah (God’s punishment)

- Abraham and Isaac (God is just)

- Jacob and Esau

- Joseph

- Moses

- Joshua

- David (Good commandor)

- Solomon and the Queen of Sheba

The general theme is that of salvation based on Latin and Greek patristic tradition. Very shocking for the time, Ghiberti places in the center of the first panel the creation of Eve, that of Adam appearing at the bottom left.

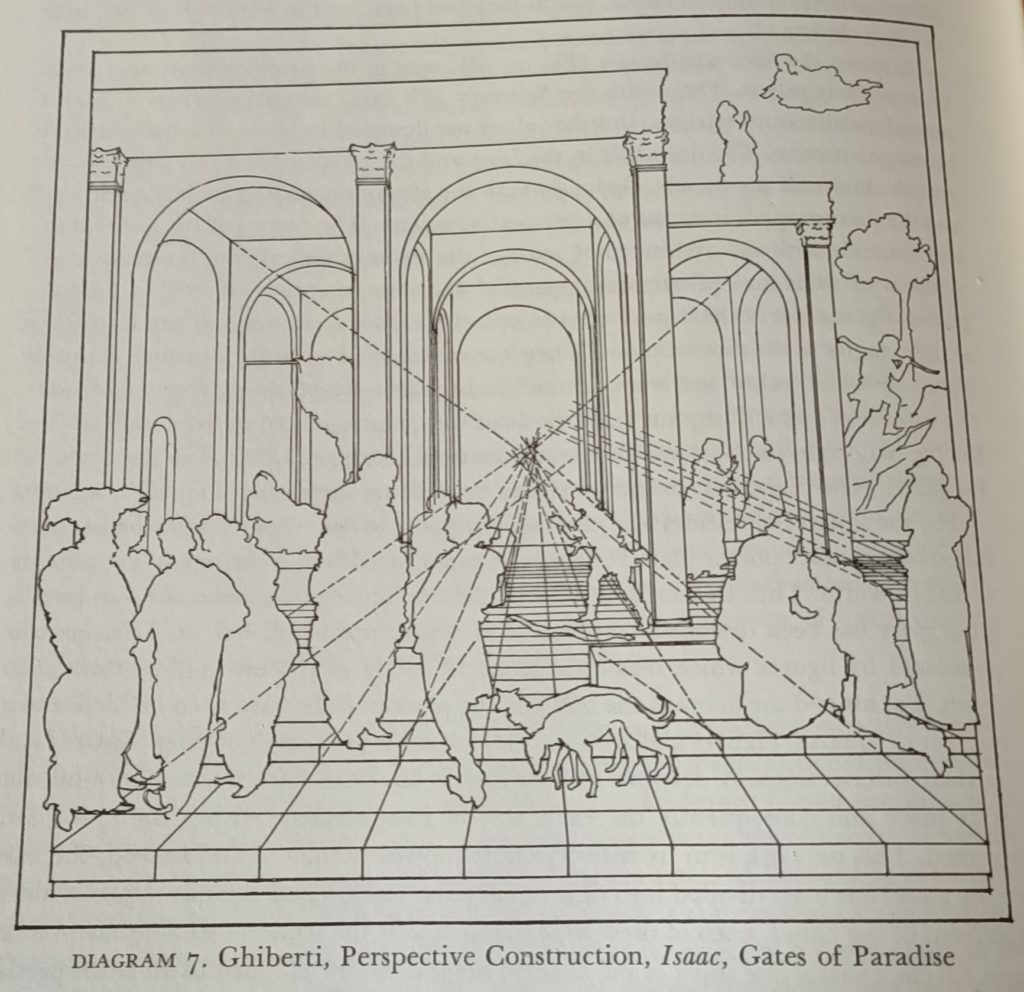

After the first three panels, focusing on the theme of sin, Ghiberti began to highlight more clearly the role of God the Savior and the foreshadowing of Christ’s coming. Subsequent panels are easier to understand. One example is the panel with Isaac, Jacob and Esau where the figures are merged with the surrounding landscape so that the eye is led toward the main scene represented in the top right.

Many of the sources for these scenes were written in ancient Greek, and since knowledge of Greek at that time was not so common, it appears that Ghiberti’s “theological advisor” was Ambrogio Traversari (1386-1439), with whom he had many exchanges.

Traversari was a close friend of Nicolas of Cusa (1401-1464), a protector of Piero della Francesca (1412-1492) and a key organizer of the Ecumenical Council of Florence of 1438-1439, which attempted to put an end to the schism separating the Church of the East from that of the West.

Perspective

The bronze reliefs, known for their vivid illusion of deep space in relief, are one of the revolutionary events that epitomize the Renaissance. In the foreground are figures in high relief, which gradually become less protruding thereby exploiting the full illusionistic potential of the stiacciato technique later brought to its high point by Donatello. Using this form of “inbetweenness”, they integrate in one single image, what appears both as a painting, a low relief as well as a high relief. Or maybe one has to look at it another way: these are flat images traveling gradually from a surface into the full three dimensions of life, just as Ghiberti, in one of the first self-portraits of art history, reaches his head out of a bronze medal to look down on the viewers. The artist desired much more than perspective, he wanted breathing space!

This new approach will influence Leonardo Da Vinci (1452-1517). As art historian Daniel Arasse points out :

(…) It was in connection with the practice of Florentine bas-relief, that of Ghiberti at the Gate of Paradise (…) that Leonardo invented his way of painting. As Manuscript G (folio 23b) would much later state, ‘the field on which an object is painted is a capital thing in painting. (…) The painter’s aim is to make his figures appear to stand out from the field’ – and not, one might add, to base his art on the alleged transparency of that same field. It is by the science of shadow and light that the painter can obtain an effect of emergence from the field, an effect of relief, and not by that of the linear perspective.

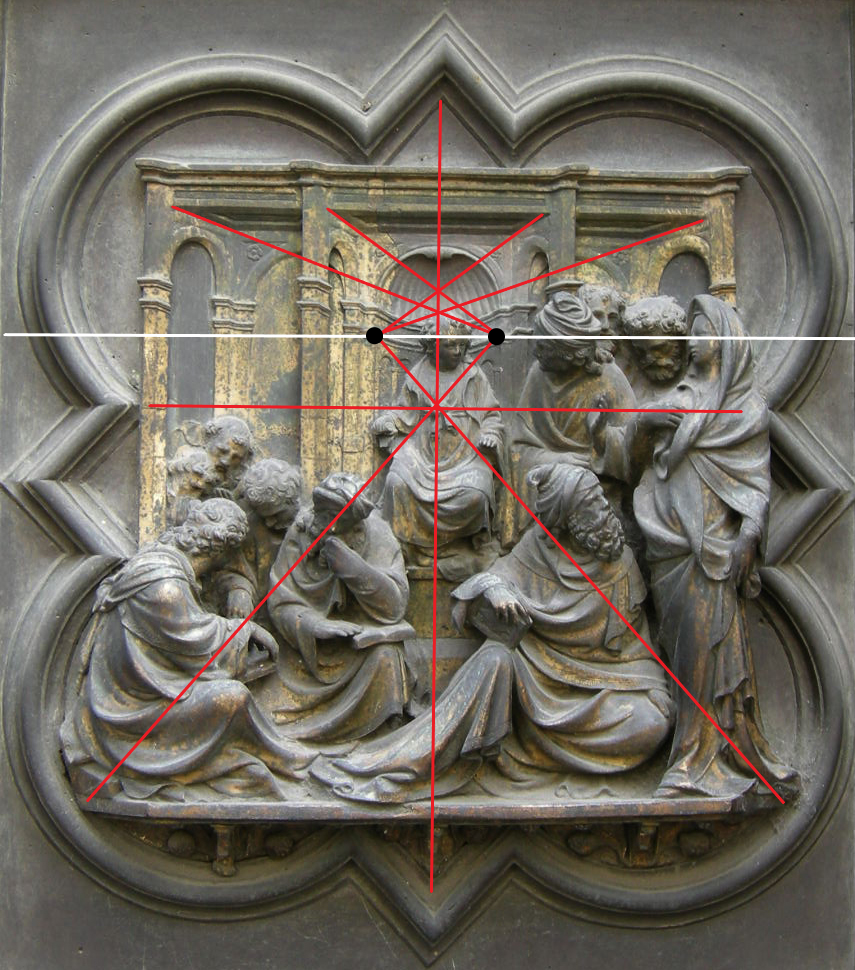

Donatello

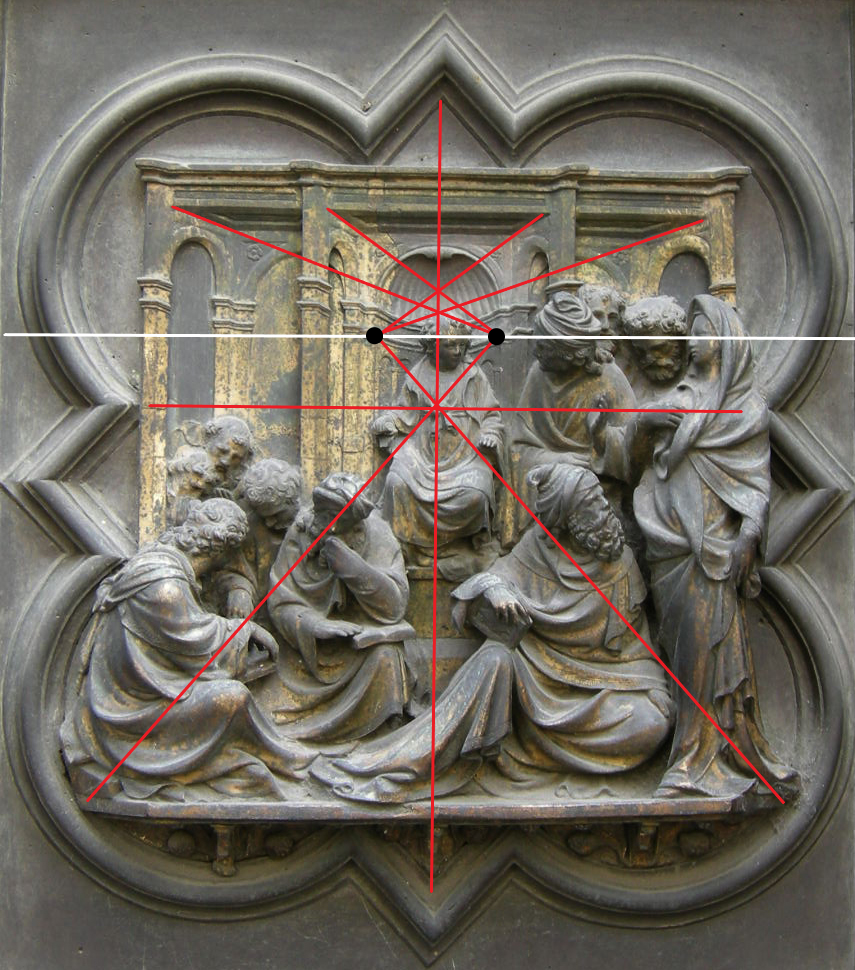

At the beginning of the 15th century, several theoretical approaches existed and eventuall contradicted each other. Around 1423-1427, the talentful sculptor Donatello, a young collaborator of Ghiberti, created his Herod’s Banquet, a bas-relief in the stiacciato technique for the baptismal font of the Siena Baptistery.

In this work, the sculptor deploys a harmonious perspective with a single central vanishing point. Around the same time, in Florence, the painter Massacchio (1401-1428) used a similar construction in his fresco The Trinity.

As we will see, Ghiberti, starting from the anatomy of the eye, opposed such an abstract approach in his works as well as in his writings and explored, as early as 1401, other geometrical models, called « binocular ». (see below).

Christ among the Doctors, Ghiberti, before 1424.

Christ among the Doctors, Ghiberti, before 1424.

Then, as far as our knowledge reaches, in 1407, Brunelleschi had conducted several experiments on this question, most likely based on the ideas presented by another friend of Cusa, the Italian astronomer Paolo dal Pozzo Toscanelli (1397-1482), in the latter’s now lost treaty Della Prospettiva. What we do know is that Brunelleschi sought above all to demonstrate that all perspective is an optical illusion.

Finally, it was in 1435, that the humanist architect Leon Baptista Alberti (1406-1472), in his treatise Della Pictura, attempted, on the basis of Donatello’s approach, to theorize single vanishing point perspective as a representation of a harmonious and unified three-dimensional space on a flat surface. Noteworthy but frustrating for us today is the fact that Alberti’s treatise doesn’t contain any illustrations.

However, Leonardo, who read and studied Ghiberti’s writings on, would use the latter’s arguments to indicate the limits and even demonstrate the dysfunctionality of Alberti’s “perfect” perspective construction especially when one goes beyond a 30 degres angle.

In the Codex Madrid, II, 15 v. da Vinci realizes that « as such, the perspective offered by a rectilinear wall is false unless it is corrected (…) ».

Perspectiva artificialis versus perspectiva naturalis

Alberti’s “perspectiva artificialis” is nothing but an abstraction, necessary and useful to represent a rational organization of space. Without this abstraction, it is fairly impossible to define with mathematical precision the relationships between the appearance of objects and the receding of their various proportions on a flat screen: width, height and depth.

From the moment that a given image on a flat screen was thought about as the intersection of a plane cutting a cone or pyramid, a method emerged for what was mistakenly considered as an “objective” representation of “real” three dimensional space, though it is nothing but an “anamorphosis”, i.e. a tromp-l’oeil or visual illusion.

What has to be underscored, is that this construction does away with the physical reality of human existence since it is based on an abstract construct pretending:

- that man is a single eyed cyclops;

- that vision emanates from one single point, the apex of the visual pyramid;

- that the eye is immobile;

- that the image is projected on a flat screen rather than on a curved retina.

Slanders and gossip

The crucial role of Ghiberti, an artist which “Ghiberti expert” Richard Krautheimer mistakenly presents as a follower of Alberti’s perspectiva artificialis, has been either ignored or downplayed.

Ghiberti’s unique manuscript, the three volumes of the Commentarii, which include his autobiography and which established him as the first modern historian of the fine arts, is not even fully translated into English or French and was only published in Italian in 1998.

Today, because of his attention to minute detail and figures « sculpted » with wavy and elegant lines, as well as the variety of plants and animals depicted, Ghiberti is generally presented as “Gothic-minded”, and therefore “not really” a Renaissance artist!

Giorgio Vasari, often acting as the paid PR man of the Medici clan, slanders Ghiberti by saying he wrote « a work in the vernacular in which he treated many different topics but arranged them in such a fashion that little can be gained from reading it. »

Admittedly, tension among humanists, was not uncommon. Self-educated craftsmen, such as Ghiberti and Brunelleschi on the one side, and heirs of wealthy wool merchants, such as Niccoli on the other side, came from entirely different worlds. For example, according to a story told by Guarino Veronese in 1413, Niccoli greeted Filippo Brunelleschi haughtily: « O philosopher without books, » to which Filippo replied with his legendary irony: « O books without philosopher ».

For sure, the Commentarii, are not written according to the rhetorical rules of those days. Written at the end of Ghiberti’s life, they may have simply been dictated to a poorly trained clerk who made dozens of spelling errors.

The humanists

The Commentarii does reveal a highly educated author and a thinker having profound knowledge of many classical Greek and Arab thinkers. Ghiberti was not just some brilliant handcraft artisan but a typical “Renaissance man”.

In dialogue with Bruni, Traversari and the “manuscript hunter” Niccolo Niccoli, Ghiberti, who couldn’t read Greek but definitely knew Latin, was clearly familiar with the rediscovery of Greek and Arab science, a task undertaken by Boccaccio’s and Salutati’s “San Spirito Circle” whose guests (including Bruni, Traversari, Cusa, Niccoli, Cosimo di Medici, etc.) later would convene every week at the Santa Maria degli Angeli convent. Ghiberti exchanges moreover with Giovanni Aurispa, a collaborator of Traversari who brought back from Byzantium, years before Bessarion, the whole of Plato’s works to the West.

Amy R. Bloch, in her well researched study Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise, Humanism, History, and Artistic Philosophy in the Italian Renaissance (2016), writes that « Traverari and Niccoli can be tied directly to the origins of the project for the Gates and were clearly interested in sculptural commissions being planned for the Baptistery. On June 21, 1424, after the Calima requested from Bruni his program for the doors, Traversari wrote to Niccoli acknowledging, in only general terms, Niccoli’s ideas for the stories to be included and mentioning, without evident disapproval, that the guild had instead turned to Bruni for advice. »

Palla Strozzi

Ghiberti’s patron, sometimes advisor, and close associate was Palla Strozzi (1372-1462), who, besides being the the richest man in Florence with a gross taxable assets of 162,925 florins in 1427, including 54 farms, 30 houses, a banking firm with a capital of 45,000 florins, and communal bonds, was also a politician, a writer, a philosopher and a philologist whose library contained close to 370 volumes in 1462.

Just as Traversari and Bruni, Strozzi learned Latin and studied Greek under the direction of the Byzantine scholar Manuel Chrysoloras, invited to Florence by Salutati.

Ghiberti’s close relationship with Strozzi, writes Bloch, « gave him access to his manuscripts and, as importantly, to Strozzi’s knowledge of them. »

But there was more. « The relationship between Ghiberti and Palla Strozzi was so close that, when Palla went to Venice in 1424 as one of two Florentine ambassadors charged with negociating an alliance with the Venetians, Ghiberti accompanied him in his retinue. »

Strozzi was known as a real humanist, always looking to preserve peace while strongly opposing oligarchical rule, both in Florence as in Venice.

In fact it was Palla Strozzi, not Cosimo de’ Medici, who first set in motion plans for the first public library in Florence, and he intended for the sacristy of Santa Trinita to serve as its entryway. While Palla’s library was never realized due to the dramatic political conflict knows as the Albizzi Coup that led to his exile in 1434, Cosimo who got a free hand to rule over Florence, would make the library project his own.

A bold statement

Ghiberti begins the Commentarii with a bold and daring statement for a Christian man in a Christian world, about how the art of antiquity came to be lost:

The Christian faith was victorious in the time of Emperor Constantine and Pope Sylvester. Idolatry was persecuted to such an extent that all the statues and pictures of such nobility, antiquity an perfection were destroyed and broken in to pieces. And with the statues and pictures, the theoretical writings, the commentaries, the drawing and the rules for teaching such eminent and noble arts were destroyed.

Ghiberti understood the importance of multidisciplinarity for artists. According to him, “sculpture and painting are sciences of several disciplines nourished by different teachings”.

In book I of his Commentarii, Ghiberti gives a list of the 10 liberal arts that the sculptor and the painter should master : philosophy, history, grammar, arithmic, astronomy, geometry, perspective, theory of drawing, anatomy and medecine and underlines that the necessity for an artist to assist at anatomical dissections.

As Amy Bloch underscores, while working on the Gates, in the intense process of visualizing the stories of God’s formation of the world and its living inhabitants, Ghiberti’s engagement « stimulated in him an interest in exploring all types of creativity — not only that of God, but also that of nature and of humans — and led him to present in the opening panel of the Gates of Paradise (The creation of Adam and Eve) a grand vision of the emergence of divine, natural, and artistic creation. »

The inclusion of details evoking God’s craftmanship, says Bloch, « recalls similes that liken God, as the maker of the world, to an architect, or, in his role as creator of Adam, to a sculptor or painter. Teh comparison, which ultimately derives from the architect-demiurge who creates the world in Plato’s Timaeus, appears commonly in medieval Jewish and Christian exegesis. »

Philo of Alexandria wrote that man was modeled « as by a potter » and Ambrose metaphorically called God a « craftsman (artifex) and a painter (pictor) ». Consequently, if man is « the image of God » as says Augustine and the model of the « homo faber – man producer of things », then, according to Salutati, « human affairs have a similarity to divine ones ».

The power of vision and the composition of the Eye

Concerning vision, Ghiberti writes:

I, O most excellent reader, did not have to obey to money, but gave myself to the study of art, which since my childhood I have always pursued with great zeal and devotion. In order to master the basic principles I have sought to investigate the way nature functions in art; and in order that I might be able to approach her, how images come to the eye, how the power of vision functions, how visual [images] come, and in what way the theory of sculpture and painting should be established.

Now, any serious scholar, having worked through Leonardo’s Notebooks, who then reads Ghiberti’s I Commentarii, immediately realizes that most of Da Vinci’s writings were basically comments and contributions about things said or answers to issues raised by Ghiberti, especially respecting the nature of light and optics in general. Leonardo’s creative mindset was a direct outgrowth of Ghiberti’s challenging world outlook.

In Commentario 3, 6, which deals with optics, vision and perspective, Ghiberti, opposing those for whom vision can only be explained by a purely mathematical abstraction, writes that “In order that no doubt remains in the things that follow, it is necessary to consider the composition of the eye, because without this one cannot know anything about the way of seeing.” He then says, that those who write about perspective don’t take into account “the eye’s composition”, under the pretext that many authors would disagree.

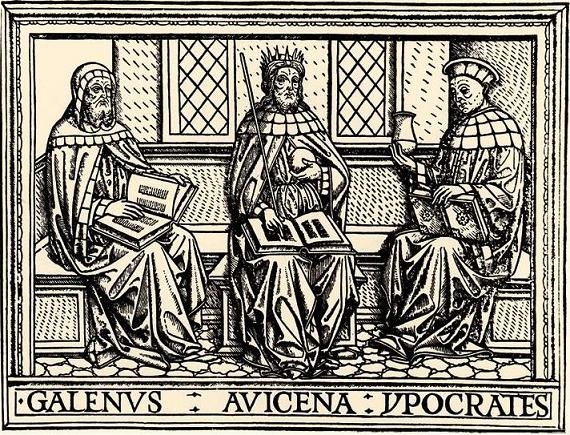

Ghiberti regrets that despite the fact that many “natural philosophers” such as Thales, Democritus, Anaxagoras and Xenophanes have examined the subject along with others devoted to human health such as “Hippocrates, Galen and Avicenna”, there is still so much confusion.

Indeed, he says, “speaking about this matter is obscure and not understood, if one does not have recourse to the laws of nature, because more fully and more copiously they demonstrate this matter.”

Avicenna, Alhazen and Constantine

Therefore, says Ghiberti:

it is necessary to affirm some things that are not included in the perspective model, because it is very difficult to ascertain these things but I will try to clarify them. In order not to deal superficially with the principles that underlie all of this, I will deal with the composition of the eye according to the writings of three authors, Avicenna (Ibn Sina), in his books, Alhazen (Ibn al Haytham) in his first volume on perspective (Optics), and Constantine (the Latin name of the Arab scholar and physician Qusta ibn Luqa) in his ‘First book on the Eye’; for these authors suffice and deal with much certainty in these subjects that are of interest to us.

This is quite a statement! Here we have “the” leading, founding figure of the Italian and European Renaissance with its great contribution of perspective, saying that to get any idea about how vision functions, one has to study three Arab scientists: Ibn Sina, Ibn al Haytham and Qusta ibn Luqa ! Cultural Eurocentrism might be one reason why Ghiberti’s writings were kept in the dark.

Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen) made important contributions to opthalmology and improved upon earlier conceptions of the processes involved in vision and visual perception in his Treatise on Optics (1021), which is known in Europe as the Opticae Thesaurus. Following his work on the camera oscura (darkroom) he was also the first to imagine that the retina (a curved surface), and not the pupil (a point) could be involved in the process of image formation.

Avicenna, in the Canon of Medicine (ca. 1025), describes sight and uses the word retina (from the Latin word rete meaning network) to designate the organ of vision.

Later, in his Colliget (medical encyclopedia), Ibn Rushd (Averroes, 1126-1198) was the first to attribute to the retina the properties of a photoreceptor.

Avicenna’s writings on anatomy and medical science were translated and circulating in Europe since the XIIIth century, Alhazen’s treatise on optics, which Ghiberti quotes extensively, had just been translated into Italian under the title De li Aspecti.

It is now recognized that Andrea del Verrocchio, whose best known pupil was Leonardo da Vinci (1452-1517) was himself one of Ghiberti’s pupils. Unlike Ghiberti, who mastered Latin, neither Verrocchio nor Leonardo mastered a foreign language.

What is known is that while studying Ghiberti’s Commentarii, Leonardo had access in Italian to a series of original quotations from the Roman architect Vitruvius and from Arab scientists such as Avicenna, Alhazen, Averroes and from those European scientists who studied Arab optics, notably the Oxford Fransciscans Roger Bacon (1214-1294), John Pecham (1230-1292) and the Polish monk working in Padua, Erazmus Ciolek Witelo (1230-1275), known by his Latin name Vitellion.

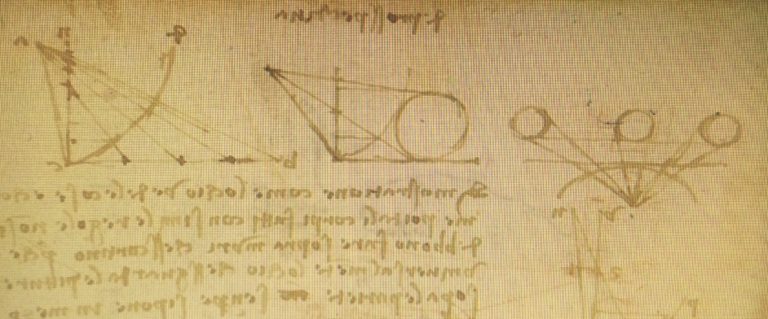

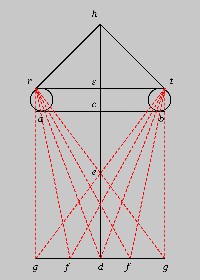

As stressed by Professor Dominque Raynaud, Vitellion introduces the principle of binocular vision for geometric considerations.

He gives a figure where we see the two eyes (a, b) receiving the images of points located at equal distance from the hd axis.

He explains that the images received by the eyes are different, since, taken from the same side, the angle grf (in red) is larger than the angle gtf (in blue). It is necessary that these two images are united at a certain point in one image (Diagram).

Where does this junction occur? Witelo says: « The two forms, which penetrate in two homologous points of the surface of the two eyes, arrive at the same point of the concavity of the common nerve, and are superimposed in this point to become one ».

The fusion of the images is thus a product of the internal mental and nervous activity.

The great astronomer Johannes Kepler (1571-1630) will use Alhazen’s and Witelo’s discoveries to develop his own contribution to optics and perspective. “Although up to now the [visual] image has been [understood as] a construct of reason,” Kepler observes in the fifth chapter of his Ad Vitellionem Paralipomena (1604), “henceforth the representations of objects should be considered as paintings that are actually projected on paper or some other screen.” Kepler was the first to observe that our retina captures an image in an inverted form before our brain turns it right side up.

Out of this Ghiberti, Uccello and also the Flemish painter Jan Van Eyck, in contact with the Italians, will construct as an alternative to one cyclopic single eye perspective revolutionary forms of “binocular” perspective while Leonardo and Louis XI’ court painter Jean Fouquet will attempt to develop curvilinear and spherical space representations.

In China, eventually influenced by Arab optical science breakthrough’s, forms of non-linear perspective, that integrate the mobility of the eye, will also make their appearance during the Song Dynasty.

Light

Ghiberti will add another dimension to perspective: light. One major contribution of Alhazen was his affirmation, in his Book of Optics, that opaque objects struck with light become luminous bodies themselves and can radiate secondary light, a theory that Leonardo will exploit in his paintings, including in his portraits.

Already Ghiberti, in the way he treats the subject of Isaac, Jacob and Esau (Figure), gives us an astonishing demonstration of how one can exploit that physical principle theorized by Alhazen. The light reflected by the bronze panel, will strongly differ according to the angle of incidence of the arriving rays of light. Arriving either from the left of from the right side, in both cases, the Ghiberti’s bronze relief has been modeled in such a way that it magnificently strengthens the overall depth effect !

While the experts, especially the neo-Kantians such as Erwin Panofsky or Hans Belting, say that these artists were “primitives” because applying the “wrong” perspective model, they can’t grasp the fact that they were in reality exploring a far “higher domain” than the mere pure mathematical abstraction promoted by the Newton-Galileo cult that became the modern priesthood ruling over “science”.

Much more about all of this can and should be said. Today, the best way to pay off the European debt to “Arab” scientific contributions, is to reward not just the Arab world but all future generations with a better future by opening to them the “Gates of Paradise”.

See all of Ghiberti’s works at the WEB GALLERY OF ART

Short Biography

- Arasse, Daniel, Léonard de Vinci, Hazan, 2011;

- Avery, Charles, La sculpture florentine de la Renaissance, Livre de poche, 1996, Paris;

- Belting, Hans, Florence & Baghdad, Renaissance art and Arab science, Harvard University Press, 2011;

- Bloch, Amy R., Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise; Humanism, History and Artistic Philosophy in the Italian Renaissance, Cambridge University Press, 2016, New York;

- Borso, Franco et Stefano, Uccello, Hazan, Paris, 2004 ;

- Butterfield, Andrew, Verrocchio, Sculptor and painter of Renaissance Florence, National Gallery, Princeton University Press, 2020 ;

- Butterfield, Andrew, Art and Innovation in Ghiberti’s Gates of Paradise, High Museum of Art, Yale University Press, 2007;

- Kepler, Johannes, Paralipomènes à Vitellion, 1604, Vrin, 1980, Paris;

- Krautheimer, Richard and Trude, Lorenzo Ghiberti, Princeton University Press, New Jersey, 1990;

- Martens, Maximiliaan, La révolution optique de Jan van Eyck, dans Van Eyck, Une révolution optique, Hannibal – MSK Gent, 2020.

- Pope-Hennessy, John, Donatello, Abbeville Press, 1993 ;

- Radke, Gary M., Lorenzo Ghiberti: Master Collaborator; The Gates of Paradise, Lorenzo Ghiberti’s Renaissance Masterpiece, High Museum of Atlanta and Yale University Press, 2007;

- Rashed, Roshi, Geometric Optics, in History of Arab Sciences, edited by Roshdi Rashed, Vol. 2, Mathematics and physics, Seuil, Paris, 1997.

- Raynaud, Dominique, L’hypothèse d’Oxford, essai sur les origines de la perspective, PUF, 1998, Paris.

- Raynaud, Dominique, Ibn al-Haytham on binocular vision: a precursor of physiological optics, Arabic Sciences and Philosophy, Cambridge University Press (CUP), 2003, 13, pp. 79-99.

- Raynaud, Dominique, Perspective curviligne et vision binoculaire. Sciences et techniques en perspective, Université de Nantes, Equipe de recherche: Sciences, Techniques, et Sociétés, 1998, 2 (1), pp.3-23.;

- Vereycken, Karel, interview with People’s Daily: Leonardo Da Vinci’s « Mona Lisa » resonates with time and space with traditional Chinese painting, 2019.

- Vereycken, Karel, Uccello, Donatello, Verrocchio and the art of military command, 2022.

- Vereycken, Karel, The Invention of Perspective, Fidelio, 1998.

- Vereycken, Karel, Van Eyck, un peintre flamand dans l’optique arabe, 1998.

- Vereycken, Karel, Mutazilism and Arab astronomy, two bright stars in our firmament, 2021.

- Walker, Paul Robert, The Feud That Sparked the Renaissance, How Brunelleschi and Ghiberti changed the World, HarperCollins, 2002.