Catégorie : Comprendre

Articles, analyses et conférences pédagogiques.

Articles, analyses et conférences pédagogiques.

L’histoire de l’art avec le regard d’un amoureux de toutes les renaissances.

FR/EN/NE/GE/IT/ES

AUDIO: Bruegel’s Fall of Empire (Icarus)

TO LISTEN TO THIS AUDIO, CLICK HERE TO OPEN WEBPAGE

Further information on Bruegel:

- Portement de croix: redécouvrir Bruegel grâce au livre de Michael Gibson (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- ENTRETIEN Michael Gibson: Pour Bruegel, le monde est vaste (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio)

- Pierre Bruegel l’ancien, Pétrarque et le Triomphe de la Mort (FR en ligne) + EN online.

- A propos du film « Bruegel, le moulin et la croix » (FR en ligne).

- L’ange Bruegel et la chute du cardinal Granvelle (FR en ligne).

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s « Dulle Griet » (Mad Meg): we see her madness, but do we see ours? (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Theodicy: The Fall of the Rebel Angels. (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Fall of Empire (Icarus) (EN)

- AUDIO: What Bruegel’s snow landscape teaches us about human fragility (EN)

AUDIO: Goya asks us to make sure Truth raises again

AUDIO: What Bruegel’s snow landscape teaches us about human fragility

OPEN WEBPAGE TO LISTEN TO AUDIO: CLICK HERE

Further information on Bruegel:

- Portement de croix: redécouvrir Bruegel grâce au livre de Michael Gibson (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- ENTRETIEN Michael Gibson: Pour Bruegel, le monde est vaste (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio)

- Pierre Bruegel l’ancien, Pétrarque et le Triomphe de la Mort (FR en ligne) + EN online.

- A propos du film « Bruegel, le moulin et la croix » (FR en ligne).

- L’ange Bruegel et la chute du cardinal Granvelle (FR en ligne).

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s « Dulle Griet » (Mad Meg): we see her madness, but do we see ours? (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Theodicy: The Fall of the Rebel Angels. (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Fall of Empire (Icarus) (EN)

- AUDIO: What Bruegel’s snow landscape teaches us about human fragility (EN)

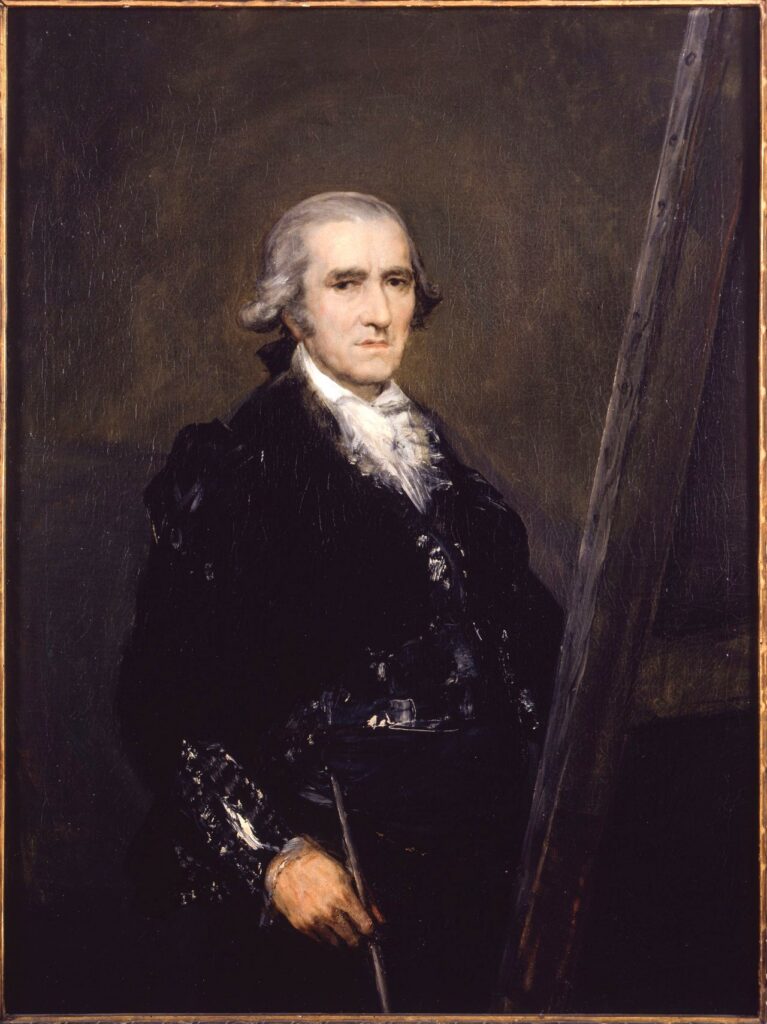

AUDIO: Goya’s Simpleton not simple

For a complete and detailed study of Goya’s life and work, see my article online in EN, FR and ES.

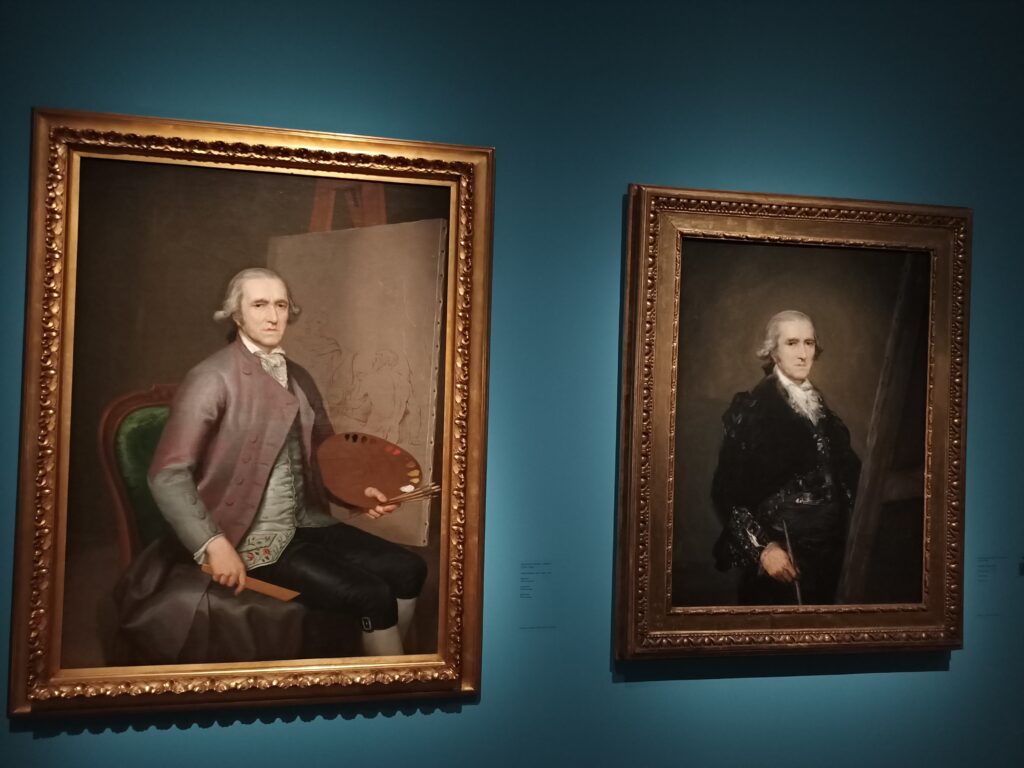

AUDIO: Goya’s portrait of Bayeu

For a complete and detailed study of Goya’s life and work, see my article online in EN, FR and ES.

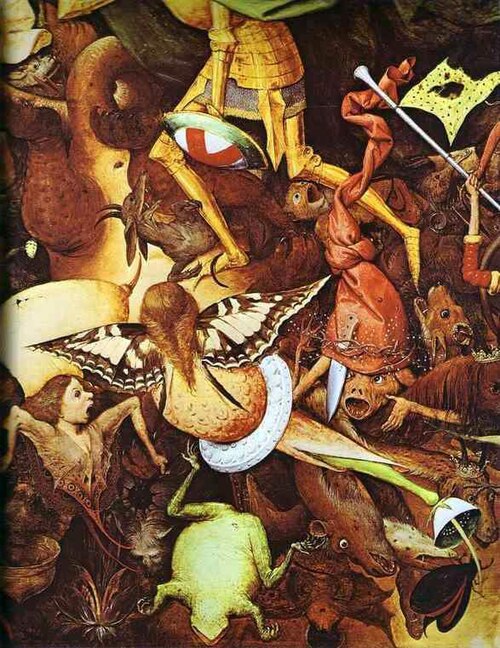

AUDIO – Bruegel’s Theodicy: The Fall of the Rebel Angels

Further information on Bruegel:

- Portement de croix: redécouvrir Bruegel grâce au livre de Michael Gibson (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- ENTRETIEN Michael Gibson: Pour Bruegel, le monde est vaste (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio)

- Pierre Bruegel l’ancien, Pétrarque et le Triomphe de la Mort (FR en ligne) + EN online.

- A propos du film « Bruegel, le moulin et la croix » (FR en ligne).

- L’ange Bruegel et la chute du cardinal Granvelle (FR en ligne).

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s « Dulle Griet » (Mad Meg): we see her madness, but do we see ours? (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Theodicy: The Fall of the Rebel Angels. (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Fall of Empire (Icarus) (EN)

- AUDIO: What Bruegel’s snow landscape teaches us about human fragility (EN)

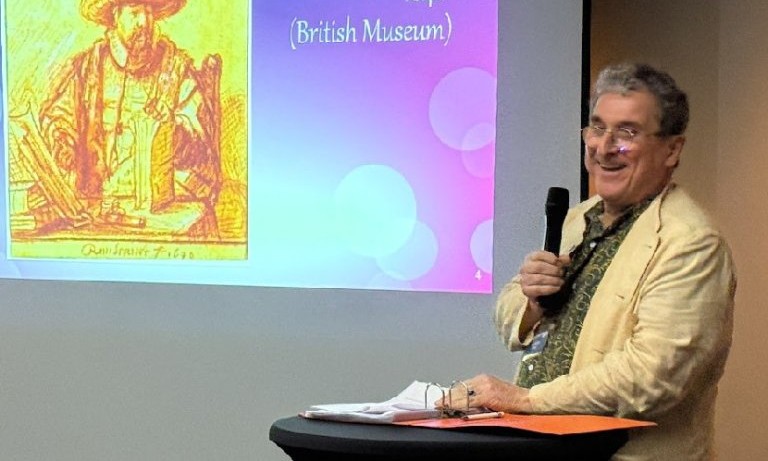

Rembrandt’s Anslo, the science of painting the « invisible »

Cet article en FR

this article in RU see bottom of this page

Lecture of Karel Vereycken, painter-engraver and historian, at the Nov. 8-9 International Paris joint conference organized by Solidarité & Progrès and the Schiller Institute.

I want this presentation to be more like a kind of « workshop ». Therefore I ask people who “know” not to immediately jump in with their answers to my questions but allow people not yet familiar with this domain to have the opportunity to express themselves and bring up their hypothesis.

In commercial contemporary art, the only science involved is to give up any form of rationality and to flap out any emotion which takes over the artist, often more “down-lifting” than “up-lifting”. But in well composed works of art, based on metaphorical paradoxes, there is a “science of composition”, elevating ideas and emotions, by a combination of invention and the skills of representation.

Very few artists allowed us to enter the back stage of their creative mind. One of them was the great American poet Edgar Allan Poe who, in 1846, in his “Philosophy of Composition” explained the genesis of his famous poem The Raven composed one year earlier.

Humanity is very lucky to have Rembrandt’s “Cornelis Anslo and his wife”, a the large oil painting on canvas done by Rembrandt in 1641, currently in the Gemäldegalerie of Berlin.

By examining the preparatory drawings and how they were changed during the creation process, we can in part read the footsteps of the creative process and lift a bit the curtain on Rembrandt’s creative genius.

Anslo and the Mennonites

On the painting, we see the Mennonite preacher Cornelis Anslo sitting at a table with some large books on his right and seemingly uttering words of consolation to a woman, most probably his wife.1

The composition is highly asymmetrical, quite unusual at that time. The low viewpoint from which the table with the books is seen, determines to a great extent the effect the painting makes. It is as if Anslo delivers a sermon from a pulpit.

The painting is quite large: 1m73 high and 207 cm large. The man with the black hat is Cornelis Claesz Anslo (1592-1646), a rich shipowner and cloth merchant. He was born in Amsterdam as the fourth son of the Norwegian-born Dutch cloth merchant Claes Claesz. « Anslo » (meaning “from Oslo”). Some pretend he has a fur coat because the painting was executed in winter, but the fur here is nothing but a sign of wealth, success and status. Anslo’s brothers were big names of the drapers guild that ran Amsterdam’s cloth industry. They made big money by selling the sort of carpets here on the table.

But Cornelis was also a deeply religious person for which religion means action rather than words alone. After getting married he created an almshouse for destitute old women. Well educated, he became then a preacher at the Grote Spijker, the church of the Waterlanders, the Mennonites of Amsterdam.

The Mennonites were a Dutch religious grouping originally founded by Simon Menno (1496-1561), a priest who left the Catholic faith and added his own branch to the protestant reformation. Some of the Amish people in the US are descendants of the Dutch and Flemish Mennonites.

It would be too long here to go into their history. In short they saw themselves as a gathering of Christians willing to live in the image of God. They didn’t want an official church. They just got together, read the Bible and tried to transform its message in concrete deeds. For example, the Mennonites took the scripture seriously when it said that Jesus told us to“Love our enemies and pray for those who persecute us”. As a result, the Mennonites decided they never would participate in war or go to war. So they were not exactly appreciated by the other religious faiths of that time, most of them engaged in battles. While many of his acquaintances were, Rembrandt never was a formal member of the Mennonites but he clearly identified with some aspects of their peace-loving worldview.2

Getting to work

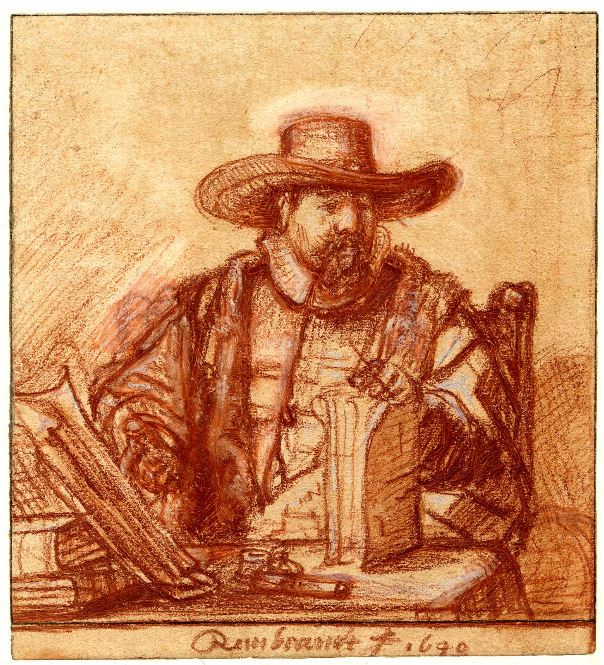

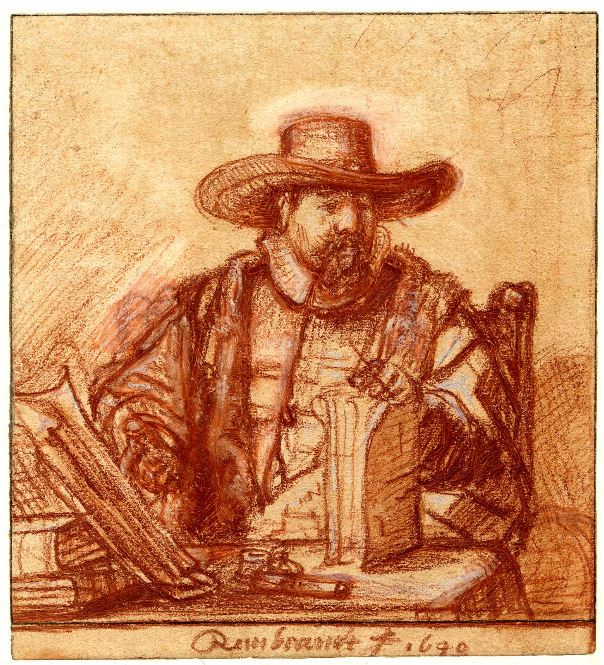

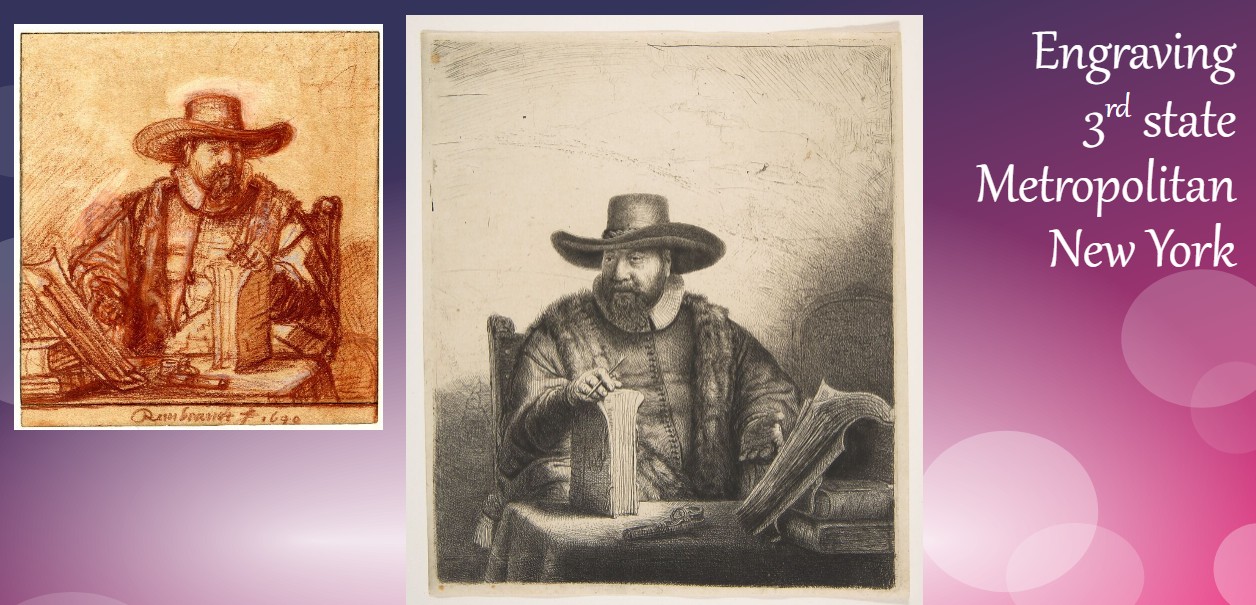

So in 1640-41, Anslo turned to Rembrandt to have his portrait done. The preacher probably asked the painter to do a sketch to get an idea of how the final portrait would look like. In the first drawing with red chalk in the British Museum, one sees the preacher.

QUESTION: What is special about this drawing ?

AUDIENCE: ….

KAREL: he holds his pen in his left hand, because the drawing is done to prepare for an etching. If you copy the image on a copper or zinc plate and then print it, you get a mirror image, which means that in the printed etching, Anslo appears as having a pen in his right hand, since the mirror image inverses the directionality. You have to plan that from the start.

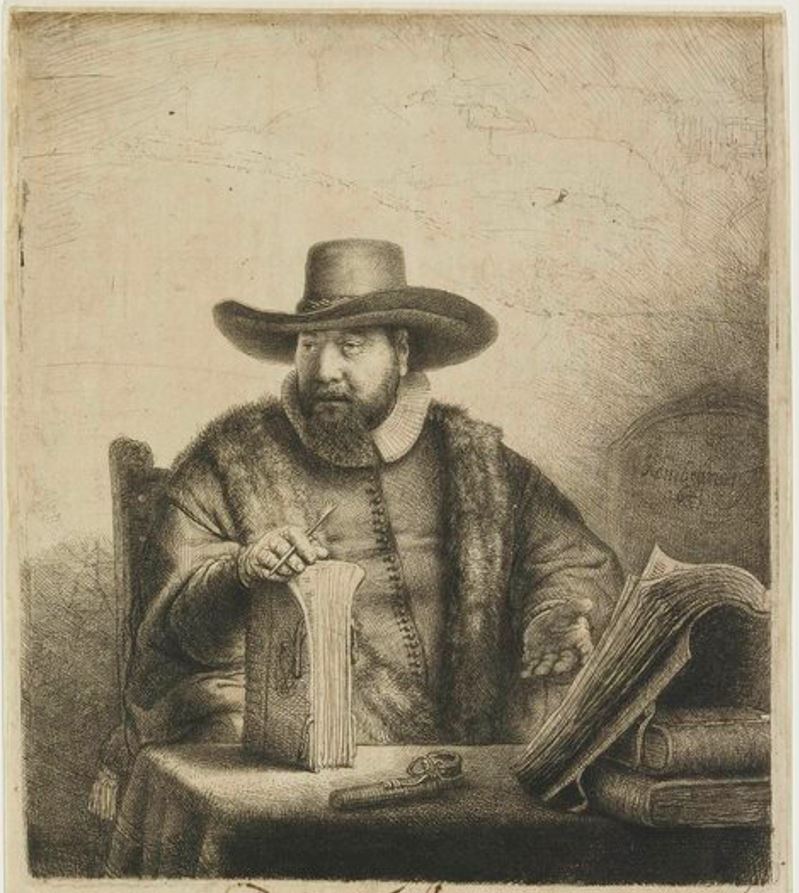

Then we have the etching of 1641 in the Met.

QUESTION: What is special about the etching as compared to the drawing?

AUDIENCE: ….

KAREL: He added empty space. Why?

AUDIENCE: …

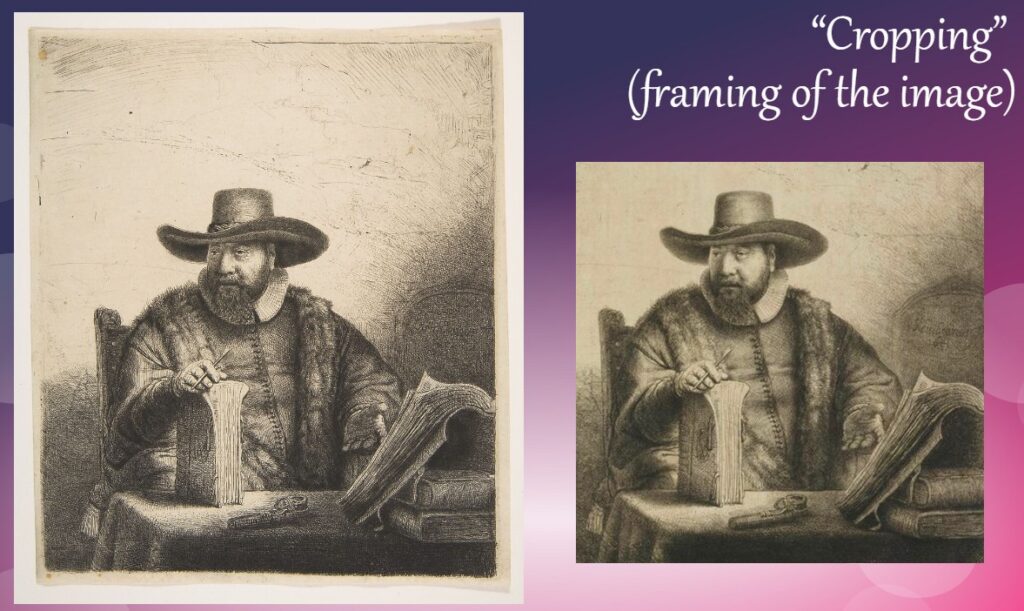

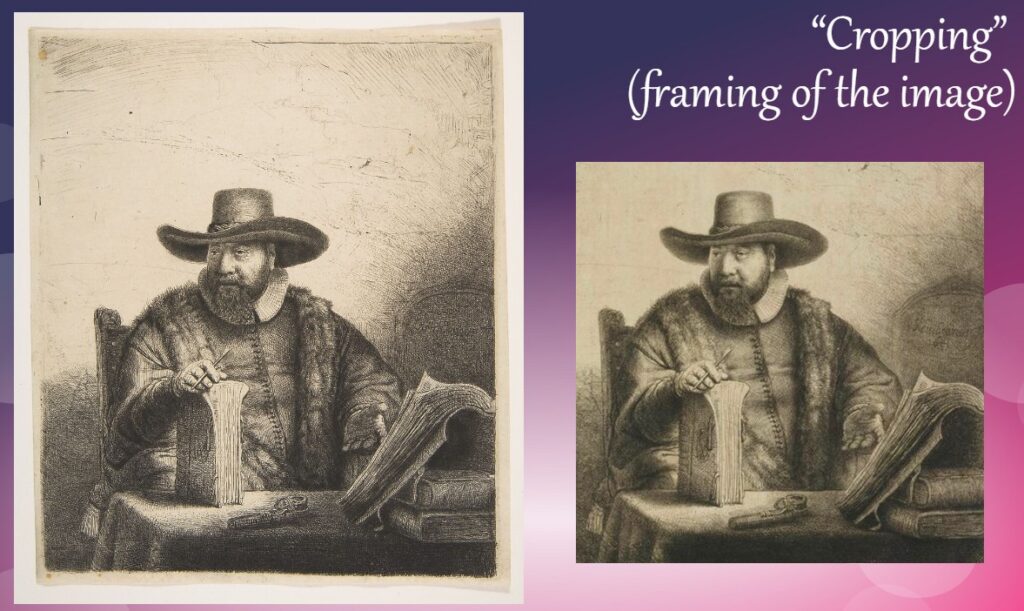

KAREL: In a good art school, you learn how to do “cropping” (re-framing) the image

KAREL: But, wait a minute, was the added space really empty?

AUDIENCE: …

KAREL: In fact, he added two things:

–one, a nail in the wall behind him (very aesthetic!);

–two: a painting put down on the floor with the image turned towards the wall (also very esthetic).

Vondel and Poetry

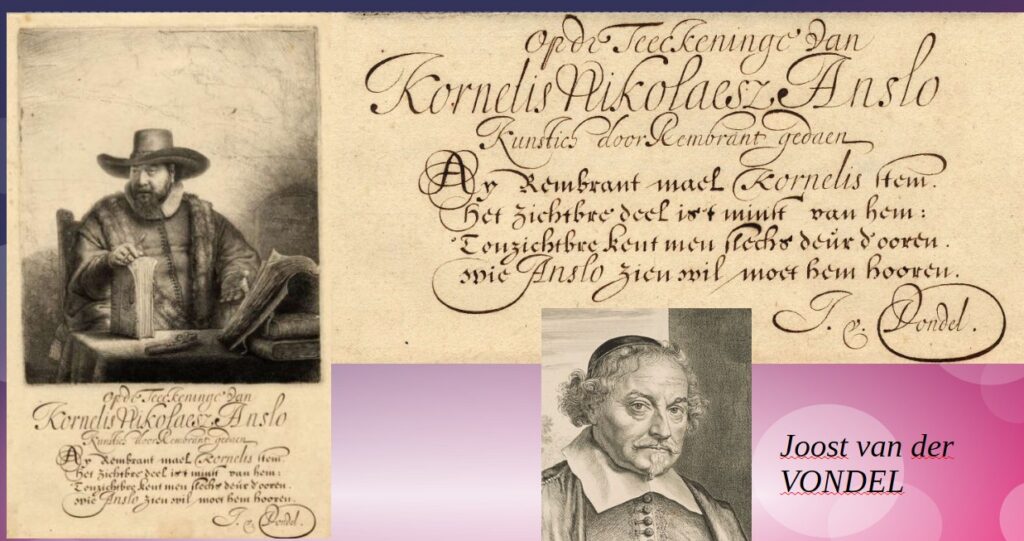

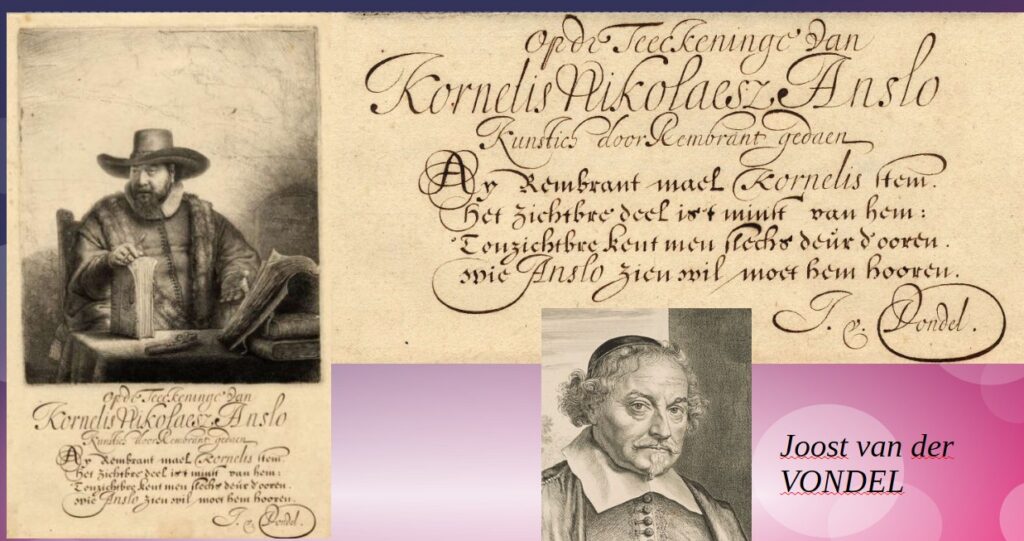

Strange? Not really. To come to an answer we need to go around it. What is hardly known, is that underneath the printed etching one finds a short poem of Joost van der Vondel, considered the greatest poet of the Dutch language:

It reads in Flemish:

« Op de Teekeninge van / Kornelis Nikolaesz Anslo /

Kunstich door Rembrandt gedaen /

Ay Rembrandt mael Kornelis stem /

het zichtbare deel is’t minst van hem /

‘t onzichtbare kent men slecht deur d’ooren /

wie Anslo zien wil, moet hem hooren. /

J. v. Vondel »

Translated to English:

« On the drawing of Kornelis Nikolaesz Anslo/

Artfully done by Rembrandt

“O, Rembrandt, paint Cornelis’s voice.

The visible part is the least of him;

the invisible we know only through our ears;

he who would like to see Anslo, must hear him”.

J. v. Vondel »

Now, till 1641, Vondel was the dean of the Waterlanders, the Mennonite grouping of Amsterdam of which Anslo was a leading preacher.

In fact the poem mentions a “tekening” (drawing), and the poem can be found already on the back of the initial sketch. It is fair to think that Anslo showed Rembrandt’s preparatory sketch to Vondel, the dean of the congregation. Reacting with his poem, Vondel accomplishes three things:

- He restates the “party line”, i.e. the core belief of the Mennonites, namely that the WORD (and even more the VOICE, that is the spoken word) was superior to the image to evangelize humanity. Transforming others with your voice had a higher value then just learning.3

- Vondel gently makes it clear that his own art, poetry, is superior to that of Rembrandt, painting…

- Vondel says Rembrandt might even do better.

It is clear that Rembrandt felt challenged by the poet remarks. The etching might be a first answer of the painter since it tries to state that point with the nail showing the image taken down and placed with its front side against the wall.

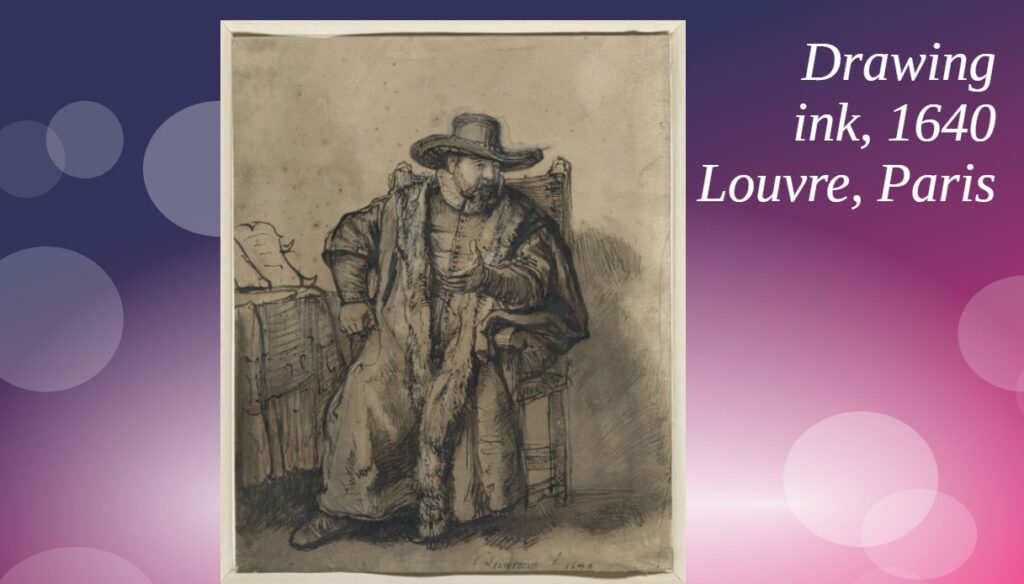

But to prepare the painting, Rembrandt, did a new sketch, now in the Louvre.

The image of the etching with the nail was certainly understood by the Mennonites of the Grote Spijker (meaning in Dutch both the « big storehouse », the nickname given to their temple, and the « big nail »…), but insufficient to reach out to a larger public like over time.

Painting the invisible

Something else had to be invented visually to present on a higher level the same argument and overcome the challenge of “painting the invisible”.

Already in the Louvre drawing, Anslo’s hand is moving to the left, or rather his head is moving to the right, leaning towards the person to which he is speaking. But in the drawing if he is not yet speaking, but “at the point” of speaking, that is a position of mid-motion-change as discussed by Lyndon LaRouche. The speaking will be absolutely manifest in the final painting. Anslo’s mouth is open and his eyebrows are raised.

Going beyond the portrait of Anslo per se, Rembrandt invents something totally new: he adds a person listening with great attention. So, in order to paint the “voice” (sound), he paints another invisible phenomenon, this one being the opposite of sound, namely silence. A voice resonating without somebody listening is as dead as the word in a book.

With this, Rembrandt overcomes the Vondel paradox and states the superiority of his own art, painting, and the fact that through, and by the image, the apparent opposites of sound and silence, can be overcome and make visible the word of God, acting through the voice of Anslo and the listening of his wife.

Now, the heavenly light of God arrives in the room, and extinguishes the earthly light of the candles to make place for the heavenly.

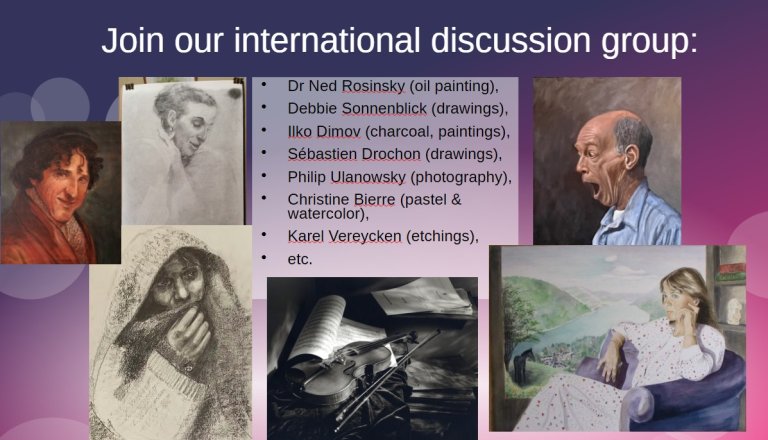

To conclude, if you want to continue this type of discussion, I invite all of you all join the international working group on art among practicing artists, initiated by Dr Ned Rosinsky. So far, it mainly includes Debbie Sonnenblick, Ilko Dimov, Dean Clark, eventually Sébastien Drochon, Agnès Farkas and Remi Lebrun, Philip Ulanowsky, Christine Bierre and myself. You see some works here (shows folder). Please get in touch with me for that.

Thanks,

SUMMARY BIOGRAPHY:

- Corpus of Rembrandt Paintings, database

https://rembrandtdatabase.org/literature/corpus.html - Filippi, Elena, Weisheit zwischen Bild und Word in Fall Rembrandt, Coincidentia, Band 2/1, 2011;

- Haak, Bob, Rembrandt, Rembrandt: his life, work and times, Thames & Hudson, 1969;

- Kauffman, Ivan J. , Seeing the Light, Essays on Rembrandt’s religious images, Academia.edu, 2015;

- Schama, Simon, Rembrandt’s Eyes, Alfred A. Knopf, 1999;

- Schwartz, Gary, Rembrandt, Flammarion, Mercatorfonds, 2006;

- Tümpel, Christian, Rembrandt, Albin Michel, Mercatorfonds, 1986;

- Vereycken, Karel, Rembrandt the nationbuilder, Nouvelle Solidarité, 1985;

- Vereycken, Karel, Rembrandt and the Light of Agapè, Artkarel.com, 2001;

- Wright, Christopher, Rembrandt, Citadelles & Mazenot, 2000.

- Experts have often disagreed about the identity of the woman. Is it his mother, his wife, or a servant of the almshouse founded by Anslo. In 1767, Camelis van der Vliet, the governor of the almshouse, reported about a passage of the archives showing that Anslo preached the gospel not only in public but also “to’zijn vrouw en kinderen; gelijk hij ook dus wonderbaarlijk fraai verbeeld word in voorgemelde schilderij, sprekende tegen zijn vrouw over den bijbel, welke op een tafel bij zig open legt, en waama zijn vrouw, op eene onnavolgelijke wijze konstig verbeeld word aandagtig en ingespannen te horen’” (He preached “to his wife and children; just as he is most wonderfully portrayed in the aforementioned painting, speaking to his wife about the bible which lies open before him, to which his wife, depicted in an inimitably artful fashion, listens with devout attention”). Furthermore this woman is not dressed like a destitute inhabitant of an almshouse, but wholly inline with her position as the wife of a wealthy merchant. The painting, done for Anslo’s private house, only became property of the almshouse many years after his lifetime. ↩︎

- In 1686, the Italian art critic Filippo Baldinucci stated that “The artist professed in those days the religion of the Menists (Mennonites).” Recent research proves that Rembrandt had close ties with Amsterdam’s Waterlander Mennonite Community, particularly through Hendrick Uylenburgh, a Mennonite art dealer who ran an artists’ studio in which Rembrandt worked from 1631 to 1635. Rembrandt became chief painter of the studio and in 1634 married Van Uylenburgh’s first cousin Saskia van Uylenburgh, who wasn’t a Mennonite. ↩︎

- The conflict between VOICE, WORD and IMAGE, had sparked in 1625 had a violent dispute among the Amsterdam Waterlanders with a one faction saying that the written word “was dead” and that what was important, was the living word, that is Jesus, who was alive as the “inner word” of Christians. Anslo intervened by publishing an anonymous pamphlet aimed to prevent a schism. ↩︎

Rembrandt, la science de « peindre l’invisible »

article in EN online on this website

article in RU at the bottom of this page

Intervention de Karel Vereycken, peintre-graveur, historien, vice-président de Solidarité & Progrès, lors de la conférence organisée par S&P et l’Institut Schiller à Paris, les 8 et 9 novembre 2025.

Je souhaite que cette présentation prenne la forme d’un atelier. C’est pourquoi je demande à ceux qui « savent déjà » ne pas répondre immédiatement à mes questions, mais de laisser la parole à ceux qui ne sont pas encore familiarisés avec ce domaine afin qu’ils puissent s’exprimer et formuler leurs hypothèses.

Dans l’art contemporain commercial, la seule science dont il est question consiste à renoncer à toute forme de rationalité et à laisser libre cours à une émotion quelconque qui s’empare de l’artiste, souvent plus dégradante qu’élévatrice. Cependant, dans les œuvres fondées sur des paradoxes métaphoriques, il existe une véritable « science de la composition », qui élève les idées et les émotions en mobilisant une combinaison de l’invention et de la maîtrise de la représentation.

Peu d’artistes nous ont permis de pénétrer dans les coulisses de leur processus créatif. L’un d’eux fut le grand poète américain Edgar Allan Poe qui, en 1846, dans sa Philosophie de la composition, expliqua la genèse de son célèbre poème Le Corbeau, composé un an auparavant.

L’humanité a la chance de pouvoir admirer « Cornelis Anslo et sa femme » de Rembrandt, une grande peinture à l’huile sur toile réalisée en 1641 et conservée à la Gemäldegalerie de Berlin. L’étude des dessins préparatoires et de leurs modifications au cours du processus de création nous permet de lever en partie le voile sur les étapes de ce processus et d’entrevoir le génie créatif de Rembrandt.

Anslo et les mennonites

Sur le tableau, on voit le prédicateur mennonite Cornelis Anslo assis à une table couverte de gros livres, s’adressant à une femme, très probablement son épouse.1

La composition est très asymétrique, ce qui était assez inhabituel pour l’époque. Le point de vue en contre-plongée, d’où l’on observe la table avec les livres, détermine en grande partie l’effet produit par le tableau. L’impression prévaut qu’Anslo, inspiré des saintes écritures, prononce un sermon du haut d’une chaire.

Le tableau est assez grand : 1,73 m de haut sur 2,07 m de large. L’homme au chapeau noir est Cornelis Claesz Anslo (1592-1646), un riche armateur et marchand de tissus. Il est né à Amsterdam, quatrième fils du marchand de tissus néerlandais d’origine norvégienne Claes Claeszoon Anslo. Anslo signifie « d’Oslo ». Certains prétendent qu’il porte un manteau de fourrure car le tableau a été réalisé en hiver, mais la fourrure ici n’est autre qu’un signe de richesse, de réussite et de statut social. Les frères d’Anslo étaient des figures majeures de la guilde des drapiers qui contrôlait l’industrie textile d’Amsterdam. Ils ont fait fortune en vendant des tapis comme celui-ci, posé sur la table.

Mais Cornelis était aussi un homme profondément religieux, pour qui la religion se traduisait par des actes et non par de simples paroles. Après son mariage, il fonda un hospice pour femmes âgées démunies. Instruit, il devint ensuite prédicateur à la Grote Spijker, l’église des Waterlanders, les mennonites d’Amsterdam.

Les mennonites étaient un groupe religieux néerlandais fondé à l’origine par Simon Menno (1496-1561), un prêtre qui quitta l’Église catholique pour créer sa propre branche au sein de la Réforme protestante. Certains Amish, aux États-Unis, descendent des mennonites néerlandais et flamands.

Il serait trop fastidieux de retracer leur histoire ici. En bref, ils se considéraient comme une communauté de chrétiens désireux de vivre à l’image de Dieu. Ils ne souhaitaient pas d’Église officielle. Ils se réunissaient simplement, lisaient la Bible et s’efforçaient de traduire son message en actes concrets. Par exemple, ils prenaient très au sérieux le passage des Écritures où Jésus nous invite à « aimer nos ennemis et à prier pour ceux qui nous persécutent ». De ce fait, les mennonites décidèrent de ne jamais faire la guerre à quiconque ni d’y prendre part. Ils n’étaient donc pas vraiment appréciés des autres confessions religieuses de l’époque, souvent engagées dans divers conflits armés. Contrairement à bon nombre de ses connaissances, Rembrandt n’a jamais été officiellement membre des mennonites. Il partageait néanmoins certains aspects de leur vision pacifique du monde.2

(Crédit: domaine public, British Museum.)

En 1640-1641, Anslo fit appel à Rembrandt pour son portrait. Le prédicateur demanda probablement au peintre de réaliser une esquisse afin de se faire une idée du résultat final. Le prédicateur apparaît sur le premier dessin à la sanguine conservé au British Museum.

QUESTION : Qu’y a-t-il de particulier dans ce dessin ?

PUBLIC : ….

KAREL : Alors qu’il était droitier, il tient sa plume de la main gauche, car le dessin est préparatoire à une gravure. Si l’on transfère l’image telle quelle sur une plaque de cuivre ou de zinc, puis qu’on l’imprime, on obtient une image en miroir. Ainsi, dans la gravure imprimée, Anslo apparaîtra avec une plume dans la main droite, puisque l’effet miroir inverse le sens de l’image. Il faut le prévoir dès le départ.

Nous avons ensuite la gravure de 1641, au Metropolitan Museum de New York.

QUESTION : Qu’est-ce qui différencie l’eau-forte du dessin ?

PUBLIC : ….

KAREL : Il a ajouté de l’espace vide. Pourquoi ?

PUBLIC : …

KAREL : Dans une bonne école d’art, on apprend à recadrer l’image.

à gauche, format intégral ; à droite, recadrée Metropolitan Museum, New York.

KAREL : Mais attendez une minute, cet espace supplémentaire est-il vraiment vide ?

PUBLIC : …

KAREL : En fait, il a ajouté deux choses :

- un clou dans le mur derrière lui (très esthétique !)

- un tableau posé au sol, l’image tournée vers le mur (également très esthétique).

Étrange ? Pas tant que ça, puisque la congrégation s’appelait De grote spijker (« Le grand clou », clou signifiant également le « grand magasin » ou la « grange » leur servant de temple).

Vondel et la poésie

Pas vraiment. Pour trouver une réponse, il faut faire un petit détour. Ce que l’on sait peu, c’est qu’en dessous des tirages de la gravure apparaît souvent, ajouté à la main, un court poème de Joost van der Vondel, considéré comme le plus grand poète de langue néerlandaise :

On peut y lire en néerlandais/flamand :

“Op de Teekeninge van / Kornelis Nikolaesz Anslo /

Kunstich door Rembrandt gedaen /

Ay Rembrandt mael Kornelis stem /

het zichtbare deel is’t minst van hem /

’t onzichtbare kent men slecht deur d’ooren /

wie Anslo zien wil, moet hem hooren. /

J. v. Vondel »

Traduction française :

« Ô Rembrandt, peins la voix de Cornelis.

La partie visible est la moindre de lui ;

l’invisible, nous ne le connaissons que par nos oreilles ;

celui qui veut voir Anslo doit l’entendre. »

J. v. Vondel

ou, la version rimée que m’a offerte mon amie russe:

« Rembrandt, ô peins, vibrant, la voix de Cornelis.

La part visible de lui n’est qu’une esquisse

Son invisible, c’est l’ouï qui nous le révèle;

Seul qui l’entend puisse voir Anslo tel quel.«

Jusqu’en 1641, Vondel fut le doyen des Waterlanders, le groupe mennonite d’Amsterdam dont Anslo était un prédicateur de premier plan.

Son poème mentionne un « tekening » (dessin) et, en effet, on peut déjà trouver le poème au verso de l’esquisse initiale. On peut penser qu’Anslo a montré, pour avis, l’esquisse préparatoire de Rembrandt à Vondel, le doyen de sa congrégation.

En réagissant par son poème, Vondel met en lumière trois points :

- Il affirme haut et fort la position officielle de la congrégation des mennonites, à savoir que la parole (et plus encore la voix, c’est-à-dire la parole prononcée) est supérieure à l’image pour évangéliser l’humanité. Transformer les autres par sa voix a plus de valeur que le simple apprentissage, et enfin, que pour connaître il faut enseigner.3

- Vondel fait subtilement comprendre que son propre art, la poésie, est supérieur à celui de Rembrandt, la peinture…

- Il dit que Rembrandt pourrait même faire mieux.

Il est clair que Rembrandt s’est senti interpellé par les remarques plutôt amicales du poète. La gravure pourrait constituer une première réponse du peintre, puisqu’elle souligne l’importance de la parole par cette idée du clou, symbolisant l’image décrochée et placée face contre le mur.

Mais pour préparer le grand tableau à l’huile, Rembrandt réalisa une nouvelle esquisse, aujourd’hui conservée au Louvre.

L’iconographie de la gravure était certainement comprise des mennonites, mais cela ne suffisait pas à toucher un public plus large au fil du temps. Il fallait donc inventer autre chose, visuellement parlant, pour présenter à un niveau supérieur le même argument et surmonter le défi de « peindre l’invisible ».

Déjà dans le dessin du Louvre, la main d’Anslo se déplace vers la gauche, ou plutôt sa tête vers la droite, donnant l’impression que le prédicateur se penche vers son interlocuteur. Dans ce deuxième dessin, si Anslo ne parle pas encore, bien qu’il soit « sur le point » de parler, il se trouve dans une position instable, disons de transition, entre deux mouvements, c’est-à-dire en « point de changement de mouvement » (mid-motion-change, comme l’a formulé Lyndon LaRouche).

La parole sera pleinement manifeste dans le tableau final : la bouche d’Anslo est ouverte et ses sourcils sont levés.

Mais au-delà du simple portrait d’Anslo, Rembrandt ajoute un élément totalement inédit : une personne qui écoute avec une attention extrême.

Ainsi, pour peindre la « voix » (le son), il peint un autre phénomène invisible, son contraire : le silence. Une voix qui résonne sans auditeur est aussi morte qu’un mot dans un livre.

Par là, Rembrandt surmonte le paradoxe de Vondel et affirme la supériorité de son art, la peinture, et le fait que, par l’image, les apparents opposés du son et du silence peuvent être dépassés et rendre visible la parole de Dieu, agissant à travers la voix d’Anslo et surtout l’écoute de sa femme.

Alors, la lumière céleste de Dieu pénètre dans la pièce et éteint la lumière terrestre des bougies pour faire place à la lumière céleste.

Pour conclure, si vous souhaitez poursuivre ce type de discussion, je vous invite à rejoindre le groupe de travail international sur l’art, parmi les artistes amateurs de notre mouvement. Ce groupe fut lancé par le Dr Ned Rosinsky. À ce jour, il comprend principalement son initiateur, Debbie Sonnenblick, Ilko Dimov, peut-être Sébastien Drochon, Philip Ulanowsky, Christine Bierre et moi-même. Vous pouvez voir quelques-unes de leurs œuvres ici. N’hésitez pas à me contacter à ce sujet.

Merci

BIOGRAPHIE SOMMAIRE :

- Corpus des peintures de Rembrandt, base de données

https://rembrandtdatabase.org/literature/corpus.html - Filippi, Elena, Weisheit zwischen Bild und Word in Fall Rembrandt, Coincidentia, groupe 2/1, 2011

- Haak, Bob, Rembrandt : sa vie, son œuvre et son époque, Thames & Hudson, 1969

- Kauffman, Ivan J., Voir la lumière, Essais sur les images religieuses de Rembrandt, Academia.edu, 2015

- Schama, Simon, Les yeux de Rembrandt, Alfred A. Knopf, 1999

- Schwartz, Gary, Rembrandt, Flammarion, Mercatorfonds, 2006

- Tümpel, Christian, Rembrandt, Albin Michel, Mercatorfonds, 1986

- Vereycken, Karel, Rembrandt, bâtisseur de nation, Nouvelle Solidarité, 1985

- Vereycken, Karel, Rembrandt et la lumière d’Agapè, Artkarel.com, 2001

- Wright, Christopher, Rembrandt, Citadelles et Mazenot, 2000.

- Les experts ont souvent divergé quant à l’identité de la femme. S’agit-il de sa mère, de son épouse ou d’une servante de l’hospice fondé par Anslo ? En 1767, Camelis van der Vliet, la gouvernante de l’hospice, rapporta un passage des archives indiquant qu’Anslo prêchait l’Évangile non seulement en public mais aussi « à sa femme et à ses enfants ; tout comme il est merveilleusement représenté dans le tableau susmentionné, parlant à sa femme de la Bible qui est ouverte devant lui, et que sa femme, représentée d’une manière inimitable et artistique, écoute avec une attention dévote ». A cela s’ajoute que la femme n’est pas vêtue comme une indigente pensionnaire d’un hospice, mais conformément à son statut d’épouse d’un riche marchand. Ce n’est que bien plus tard que le tableau, réalisé pour la demeure privée d’Anslo, deviendra propriété de l’hospice. ↩︎

- En 1686, le critique d’art italien Filippo Baldinucci déclara que « l’artiste professait à cette époque la religion des ménistes (mennonites) ». Des recherches récentes confirment que Rembrandt avait des liens étroits avec la communauté mennonite Waterlander d’Amsterdam, notamment par l’intermédiaire d’Hendrick Uylenburgh, un marchand d’art mennonite qui dirigeait un atelier d’artistes où Rembrandt travailla de 1631 à 1635. Rembrandt devint le peintre en chef de l’atelier et épousa en 1634 la cousine germaine de Van Uylenburgh, Saskia van Uylenburgh, qui n’était pas mennonite. ↩︎

- Le débat sur le rôle exact de la voix, de la parole et de l’image pour les prêcheurs, dégénéra en 1625 en une violente dispute entre les membres de la communauté des Waterlanders d’Amsterdam et d’ailleurs. Une faction affirmait que la parole écrite n’était qu’une voix « morte » et que seul importait la parole vivante, c’est-à-dire Jésus, qui était vivant en chacun en tant que « parole intérieure » des chrétiens. En publiant un pamphlet anonyme, Anslo a pu calmer le débat et réconcilier les croyants, évitant ainsi un schisme. ↩︎

Exposition : Estampes d’Automne, 2025

L’atelier Bo Halbirk a le plaisir de vous inviter au vernissage de sa nouvelle exposition intitulée « Estampes d’automne » le vendredi 10 octobre 2025 à 18h au 1 rue Garibaldi, Montreuil (Métro Robespierre – ligne 9).

Cette exposition réunit les œuvres de 33 artistes graveurs membres de l’atelier. Elle débutera à l’occasion des Portes Ouvertes des Ateliers d’Artistes de Montreuil.

À cette occasion, nous ouvrirons nos portes les trois premiers jours de l’exposition, de 12h à 18h. Des démonstrations d’impression et de techniques de gravure seront proposées tout au long du week-end.

En parallèle, un vide-grenier se tiendra le dimanche 12 octobre dans la rue située en face de l’atelier. Ensuite l’exposition sera visible du mardi au vendredi de 12h à 18h jusqu’au 12 décembre 2025.

Zheng He and the Chinese Maritime Expeditions

Cet article en FR

By launching its « 21st Century Maritime Silk Road », China is reconnecting with a particularly rich naval and maritime past. Its first activities in this field date back, as far as navigation in the China Sea is concerned, to the Zhou dynasty (771-256 BC).

(See also my article The Maritime Silkroad, a history of 1001 Cooperations )

By Karel Vereycken

By the Han period (1st to 3rd century CE), China was already familiar with naval techniques, including a primitive form of compass and the famous junks capable of reaching the coasts of Africa.

An activity, undoubtedly carried out by Chinese, Indian and Arab navigators, which developed, notably from the great Indian port of Calicut, over a thousand-year period, in particular under the Tang (618-907) and the Song (960-1279).

« The annual import into China of ivory, rhinoceros horn, pearls, incense and other products found specifically along the coasts of Yemen and East Africa, amounted (around 1053) to 53,000 units of account, » according to the chroniclers of the dynasty of the time.

In exchange for imperial silk, ceramics and porcelain, Chinese sailors also bought large quantities of pearls and precious objects. Many Song and Tang Chinese coins have been found, as well as porcelain, in the coastal regions of Somalia, Kenya and Tanganyika as well as the island of Zanzibar.

The XVth Century

However, the expeditions of Admiral Zheng He (1371-1433) under the Ming dynasty, at the beginning of the XVth century, are something exceptional because they were strongly oriented towards scientific exchanges.

Zheng was born a Muslim. Grandson of the governor of Yunnan Province, he became a eunuch at the court of Zhu Di, the future Yongle Emperor (1402-1424).

The latter made history by launching a series of (very) major works:

- It reinvigorates the Silk Roads;

- He restored the astronomical observatory to its former functions;

- He moved the Chinese capital from Nanking to Beijing;

- In the heart of the capital, he had the Forbidden City built by 1 million workers and craftsmen;

- It modernizes the Grand Canal to guarantee the food security of the capital;

- He expanded the system of imperial examinations for the selection of scholars;

- He had 2,180 scholars write the largest encyclopedia ever written, comprising more than 11,000 volumes;

- He appointed Admiral Zheng He as commander-in-chief of a high seas fleet tasked with publicizing and recognizing the achievements of China and its Emperor throughout the world.

Thus, between 1405 and 1433, Admiral Zheng will lead seven expeditions which will land in almost all the countries, ports and sites that count in the Indian Ocean:

- Vietnam: the kingdom of Champa, city of Cochinchina;

- Indonesia: the island of Java and Sumatra, Aru Islands, city of Palembang;

- Thailand: Siam;

- Malaysia: port of Malacca, islands of Pahang and state of Kelantan (Malaysia);

- Sri Lanka: the island of Ceylon;

- India: Kozhikode (or Calicut), capital of the state of Kerala in India;

- The Maldives Islands;

- Iran: Hormuz Island in the Persian Gulf

- Yemen: Aden;

- Somalia: Mogadishu;

- Kenya: Kingdom of Malindi (Melinde);

- Sultanate of Oman: Muscat and Dhofar;

- Saudi Arabia: Jeddah and Mecca.

The Science of Navigation

His fleet, during the first expedition between 1405 and 1407, had no fewer than 27,800 men on board 317 vessels, including 62 « treasure ships », XXL ships capable of carrying 500 people.

The largest junk is 122 metres long and 52 metres wide, it has nine masts and 3000 tonnes, while Christopher Columbus’ caravels of 1492 are only 25 metres long and 5 metres wide, its sails hoisted on only two masts and carrying only 450 tonnes!

Imitating the partitioned stems of bamboo, these ships are composed of watertight compartments which make them less vulnerable to shipwrecks and fires. The ancestral technique of watertight compartments, taken up by Western shipbuilding in the 19th century, was registered in November 2010 by UNESCO as an intangible cultural heritage of humanity.

Historians note that in Europe, shipbuilding drew its inspiration from the swimming of fish. Throughout history, our ships have sought to cut through the waves and the bow remains one of the fundamental points of our shipbuilding.

However, the Chinese note that the fish that swims underwater cannot be an example for evolving on the water. Their reference animal is the duck. No bow when it is enough to fly over the surface. The junk was therefore designed according to the shape of this sea bird. From this one, it takes its elongation, its very low draft on the front of the hull and its great width.

According to some historians, on February 2, 1421, the Yongle Emperor gathered 28 leaders and dignitaries from Asia, Arabia, the Indian Ocean and Africa.

This summit, according to Serge Michel and Michel Beuret, was

« the most international conference ever organized and which would have testified to the influence of Ming China (1368-1644), an empire then open to the world. »1

In France, in 1431, Joan of Arc was burned at the stake in Rouen…

A civilizational chasm

At the end of the 14th century, a gulf separated the level of development of China from that of a Europe ruined by the Hundred Years’ War, an unprecedented financial crash, famine and the Black Death.

For example, the library of the English king Henry V (1387-1422) consisted of only six manuscript volumes, three of which were loaned by a convent. The Vatican, for its part, possessed only about a hundred books before 1417.

While for the inauguration of the Forbidden City in Beijing in 1421, some 26,000 guests feasted on a banquet consisting of ten courses served on plates of the finest porcelain, in Europe, a few weeks later, at the wedding of Henry V to Catherine of Valois, it was salted cod on slices of stale bread that was served to the six hundred guests!

While the Chinese army could field a million men armed with firearms, the same Henry V of England, when he went to war against France the same year, had barely 5,000 fighters armed with bows, swords and pikes. And the English monarch, lacking a powerful navy, was forced to use fishing boats to cross the Channel…

Diplomacy and Prestige

Contrary to what has been said, the Ming dynasty was not concerned with seeking new trade routes, systematically supplying itself with slaves or finding land to colonize.

The sea routes used by Zheng’s fleet were already known and had been frequented by Arab merchants since the 7th century.

That this was a demonstration of Chinese prestige is demonstrated by the fact that in 1407 Zheng founded a language school in Nanking.

Sixteen translators would travel with the Chinese fleets, allowing the admiral to converse, from India to Africa, in Arabic, Persian, or even in Swahili, Hindi, Tamil and other languages.

Since religious freedom was one of the Emperor’s great virtues, Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist scholars were included in the journey.

Equally remarkable was the presence of scientists on ships so large that they allowed scientific experiments to be conducted there.

The metallurgists who had embarked for the occasion prospected in the countries where the fleet stopped. The doctors could collect plants, remedies and treatments for diseases and epidemics.

Botanists tried to acclimatize useful plants or food crops. The ships also brought seeds that the Chinese hoped to cultivate abroad.

It was during these expeditions that China established diplomatic relations with around thirty countries. The story of these exchanges has come down to us thanks to the remarkable work of his traveling companion Ma Huan.

Also a Muslim, his writings are available in a book entitled Ying-yai Sheng-lan ( The Wonders of the Oceans ).

During their last voyage, the two friends were granted the right to go as far as Mecca with a view to establishing commercial exchanges.

On his fourth expedition, National Geographic claims, Zheng met with representatives of the Sultanate of Malindi (present-day Kenya), with whom China had established diplomatic relations in 1414.

As tribute, African dignitaries offered Zheng He zebras and a giraffe, an animal the Romans called the cameleopard (half-camel, half-leopard).

In China, the Emperor hoped to one day possess a qilin , that is to say an animal as mythical as the unicorn in the West, a cross between a deer or a horse with hooves, and a lion or a dragon with a brightly colored skin.

The emperor also wanted a painting of the giraffe, a copy of which was found in 1515 in a painting by the Flemish painter Hieronymus Bosch, who had copied it from a book by Cyriacus of Ancome (1391-1452), a great Italian traveller.

Right: détail of Hieronymus Bosch’s Garden of Earthly Delights, left panel, Madrid.

Unfortunately, in May 1421, two months after the departure of the great fleet, the Forbidden City, struck by lightning, was reduced to ashes.

Interpreted as a sign from heaven, this will be the beginning of a period of national withdrawal which will lead China to abandon its projects, to even destroy, in 1479, all the documents relating to these expeditions and to interrupt its foreign trade until 1567.

Faced with the Mongol threat, China will then concentrate on the construction of the Great Wall, agriculture and education.

Today

It was not until 1963 that Zhou Enlai, during his tour of Africa, rehabilitated Admiral Zheng. In 2005, China celebrated the 600th anniversary of his first expedition and evoked his memory at the opening ceremony of the 2008 Olympic Games.

For China, Zheng’s expeditions are emblematic of its ability to promote harmonious commercial development that broke with the Western and Japanese colonial practices from which China suffered during the « 150 years of humiliation. »

President Xi rightly said in 2014:

« Countries that have tried to pursue their development goals through the use of force have failed (…) This is what history has taught us. China is committed to maintaining peace. »

NOTE:

- In his book 1421, the Year China Discovered America , the amateur historian Gavin Menzies, a former commander of the British Royal Navy, claims, on the basis of copies of old maps whose authenticity is more than questionable, that Zheng We’s men were able to reach America, even Australia, and this well before the Europeans. His publisher, who had his text completely rewritten by 130 communicators to make it a bestseller, granted him 500,000 English pounds to acquire the copyright worldwide. The Chinese, knowing full well that you have to be wary of the English especially when they flatter you, without closing the doors to further research, have so far resisted any idea of crediting his thesis. ↩︎

The Creative Principle in Painting

Discussion paper written (updated later but initially conceived in Belgium before 1980) by my beloved wife Christine (Ruth) BIERRE who was a precious source of many of my works, research and inspiration.

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on décembre 30, 2025

AUDIO: Bruegel’s Mad Meg: we see her madness, but do we see ours ?

More information on Bruegel:

Posted in Audio comments, Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur AUDIO: Bruegel’s Mad Meg: we see her madness, but do we see ours ?

Tags: antwerpen, artkarel, audio, comment, dessin, Dulle Griet, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Maagdenhuis, Mayer van den Bergh, peinture