Étiquette : Karel

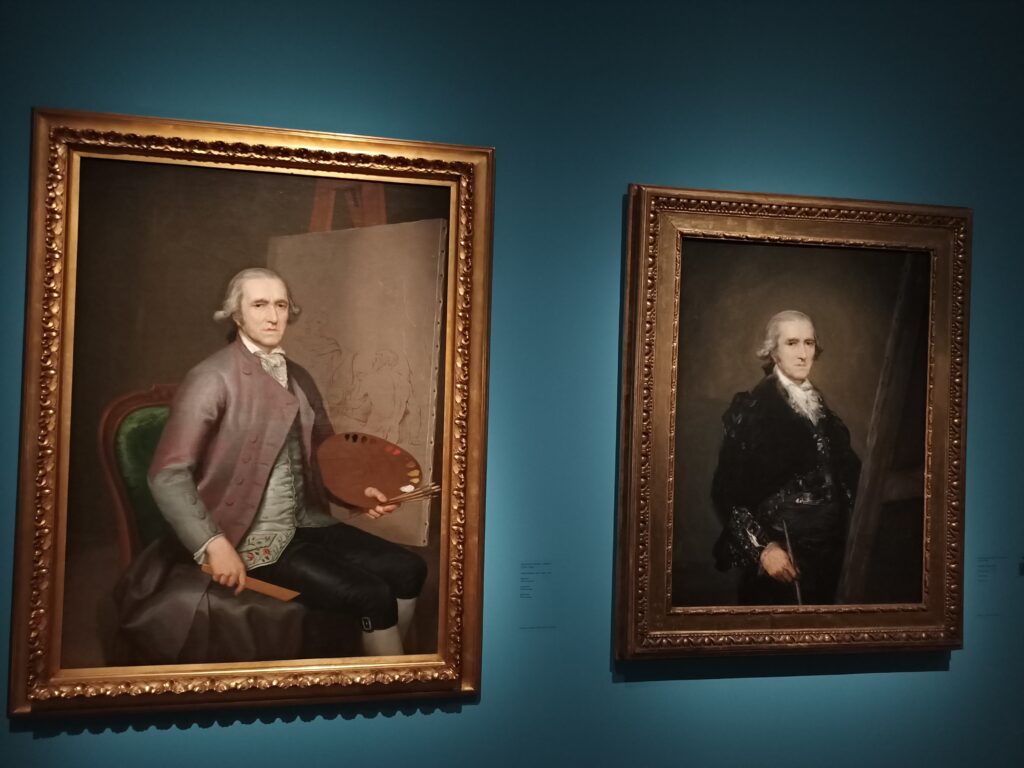

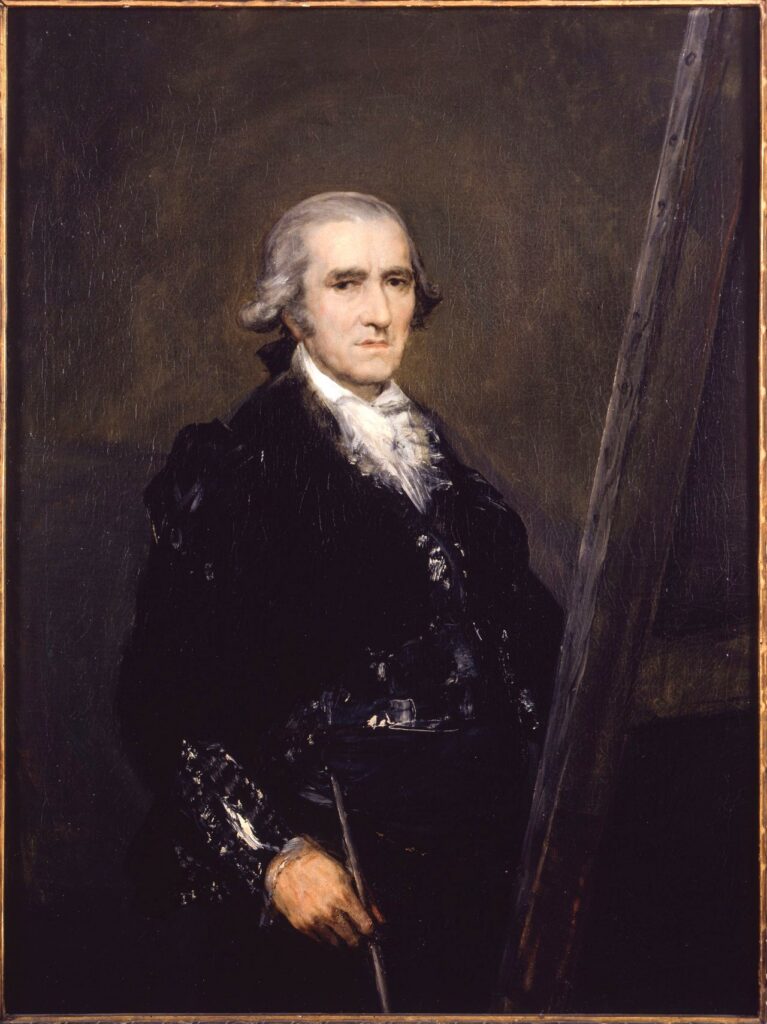

AUDIO: Goya’s portrait of Bayeu

For a complete and detailed study of Goya’s life and work, see my article online in EN, FR and ES.

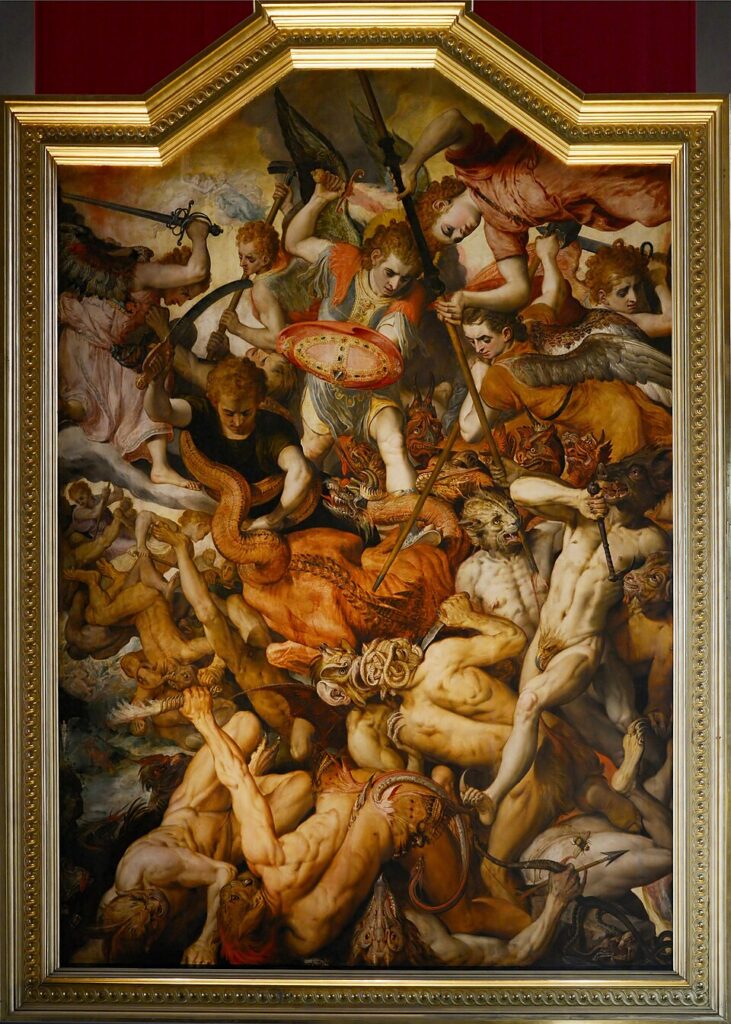

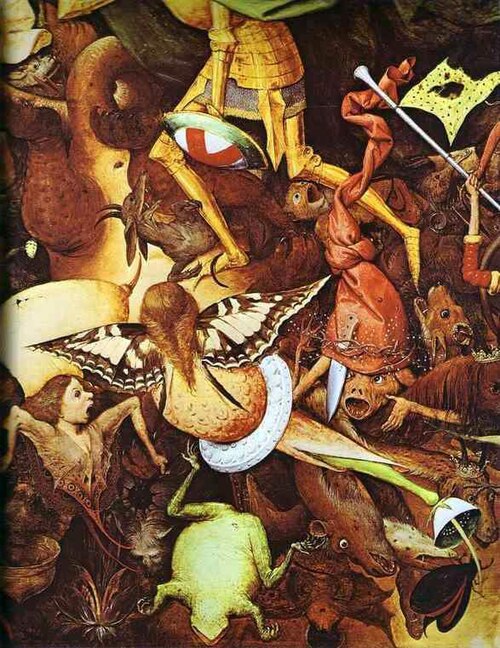

AUDIO – Bruegel’s Theodicy: The Fall of the Rebel Angels

Further information on Bruegel:

- Portement de croix: redécouvrir Bruegel grâce au livre de Michael Gibson (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio).

- ENTRETIEN Michael Gibson: Pour Bruegel, le monde est vaste (FR en ligne) + EN pdf (Fidelio)

- Pierre Bruegel l’ancien, Pétrarque et le Triomphe de la Mort (FR en ligne) + EN online.

- A propos du film « Bruegel, le moulin et la croix » (FR en ligne).

- L’ange Bruegel et la chute du cardinal Granvelle (FR en ligne).

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s « Dulle Griet » (Mad Meg): we see her madness, but do we see ours? (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Theodicy: The Fall of the Rebel Angels. (EN)

- AUDIO: Bruegel’s Fall of Empire (Icarus) (EN)

- AUDIO: What Bruegel’s snow landscape teaches us about human fragility (EN)

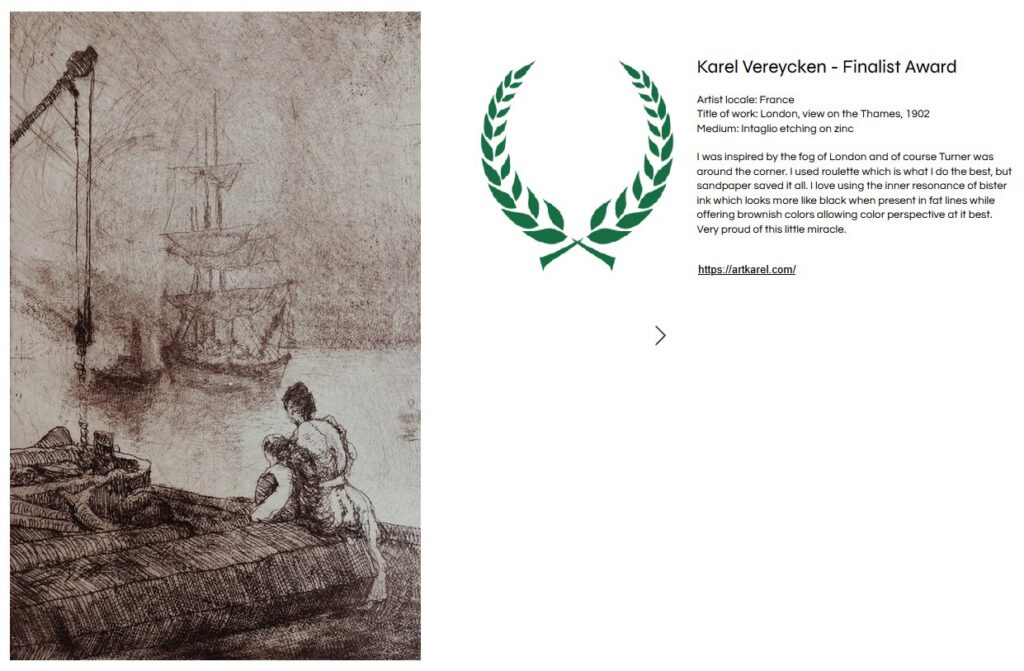

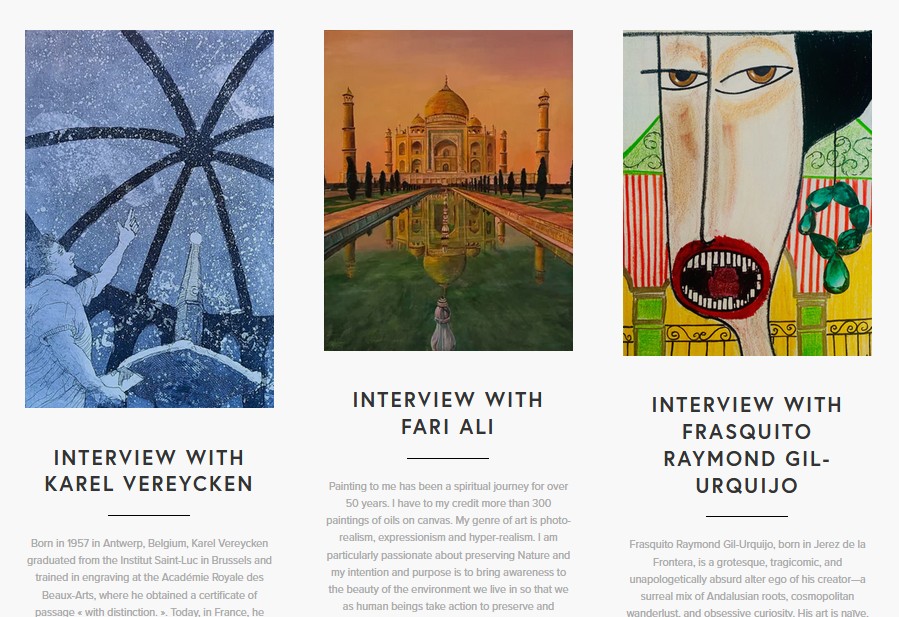

Karel Vereycken awarded Finalist prize by Camelback Gallery

On Dec. 30, 2025, Franco-Belgian painter-engraver Karel Vereycken was honored with a « Finalist Award » by Camelback Gallery, Scottsdale, Arizona for the yearly contest « My Best Work of 2025 Art Awards ».

12 Countries were represented in this exhibition including USA, Canada, Australia, UK, Germany, Poland, Japan, Romania, Mexico, France, Ukraine, Ireland.

Kassandra Kaye, the juror for this event « selected artwork based on theme, quality of work, composition, value, color, technique, depth and overall impact of the art. »

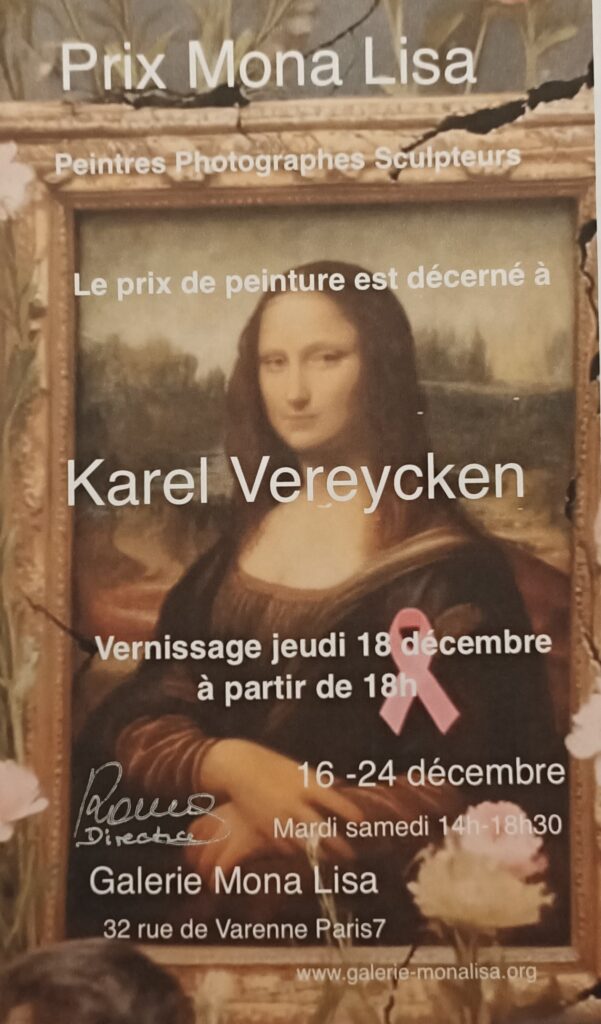

Karel Vereycken wins Paris « Mona Lisa Prize » for his art work

At the Dec. 18, 2025 opening reception (vernissage) of a collective exhibition at the Paris Galerie Mona Lisa, 32, rue de Varenne (Paris VII), Karel Vereycken was honored with the Mona Lisa Prize for painting. His work will be on show at the Galerie between Jan. 16 and Jan. 28, 2026 from Tuesday till Saturday between 2:30 and 6 pm.

Jardin d’Argenteuil

Rembrandt, la science de « peindre l’invisible »

article in EN online on this website

article in RU at the bottom of this page

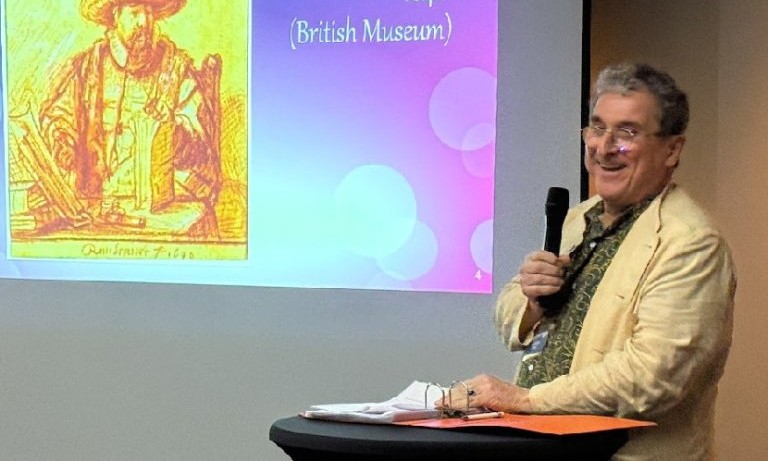

Intervention de Karel Vereycken, peintre-graveur, historien, vice-président de Solidarité & Progrès, lors de la conférence organisée par S&P et l’Institut Schiller à Paris, les 8 et 9 novembre 2025.

Je souhaite que cette présentation prenne la forme d’un atelier. C’est pourquoi je demande à ceux qui « savent déjà » ne pas répondre immédiatement à mes questions, mais de laisser la parole à ceux qui ne sont pas encore familiarisés avec ce domaine afin qu’ils puissent s’exprimer et formuler leurs hypothèses.

Dans l’art contemporain commercial, la seule science dont il est question consiste à renoncer à toute forme de rationalité et à laisser libre cours à une émotion quelconque qui s’empare de l’artiste, souvent plus dégradante qu’élévatrice. Cependant, dans les œuvres fondées sur des paradoxes métaphoriques, il existe une véritable « science de la composition », qui élève les idées et les émotions en mobilisant une combinaison de l’invention et de la maîtrise de la représentation.

Peu d’artistes nous ont permis de pénétrer dans les coulisses de leur processus créatif. L’un d’eux fut le grand poète américain Edgar Allan Poe qui, en 1846, dans sa Philosophie de la composition, expliqua la genèse de son célèbre poème Le Corbeau, composé un an auparavant.

L’humanité a la chance de pouvoir admirer « Cornelis Anslo et sa femme » de Rembrandt, une grande peinture à l’huile sur toile réalisée en 1641 et conservée à la Gemäldegalerie de Berlin. L’étude des dessins préparatoires et de leurs modifications au cours du processus de création nous permet de lever en partie le voile sur les étapes de ce processus et d’entrevoir le génie créatif de Rembrandt.

Anslo et les mennonites

Sur le tableau, on voit le prédicateur mennonite Cornelis Anslo assis à une table couverte de gros livres, s’adressant à une femme, très probablement son épouse.1

La composition est très asymétrique, ce qui était assez inhabituel pour l’époque. Le point de vue en contre-plongée, d’où l’on observe la table avec les livres, détermine en grande partie l’effet produit par le tableau. L’impression prévaut qu’Anslo, inspiré des saintes écritures, prononce un sermon du haut d’une chaire.

Le tableau est assez grand : 1,73 m de haut sur 2,07 m de large. L’homme au chapeau noir est Cornelis Claesz Anslo (1592-1646), un riche armateur et marchand de tissus. Il est né à Amsterdam, quatrième fils du marchand de tissus néerlandais d’origine norvégienne Claes Claeszoon Anslo. Anslo signifie « d’Oslo ». Certains prétendent qu’il porte un manteau de fourrure car le tableau a été réalisé en hiver, mais la fourrure ici n’est autre qu’un signe de richesse, de réussite et de statut social. Les frères d’Anslo étaient des figures majeures de la guilde des drapiers qui contrôlait l’industrie textile d’Amsterdam. Ils ont fait fortune en vendant des tapis comme celui-ci, posé sur la table.

Mais Cornelis était aussi un homme profondément religieux, pour qui la religion se traduisait par des actes et non par de simples paroles. Après son mariage, il fonda un hospice pour femmes âgées démunies. Instruit, il devint ensuite prédicateur à la Grote Spijker, l’église des Waterlanders, les mennonites d’Amsterdam.

Les mennonites étaient un groupe religieux néerlandais fondé à l’origine par Simon Menno (1496-1561), un prêtre qui quitta l’Église catholique pour créer sa propre branche au sein de la Réforme protestante. Certains Amish, aux États-Unis, descendent des mennonites néerlandais et flamands.

Il serait trop fastidieux de retracer leur histoire ici. En bref, ils se considéraient comme une communauté de chrétiens désireux de vivre à l’image de Dieu. Ils ne souhaitaient pas d’Église officielle. Ils se réunissaient simplement, lisaient la Bible et s’efforçaient de traduire son message en actes concrets. Par exemple, ils prenaient très au sérieux le passage des Écritures où Jésus nous invite à « aimer nos ennemis et à prier pour ceux qui nous persécutent ». De ce fait, les mennonites décidèrent de ne jamais faire la guerre à quiconque ni d’y prendre part. Ils n’étaient donc pas vraiment appréciés des autres confessions religieuses de l’époque, souvent engagées dans divers conflits armés. Contrairement à bon nombre de ses connaissances, Rembrandt n’a jamais été officiellement membre des mennonites. Il partageait néanmoins certains aspects de leur vision pacifique du monde.2

(Crédit: domaine public, British Museum.)

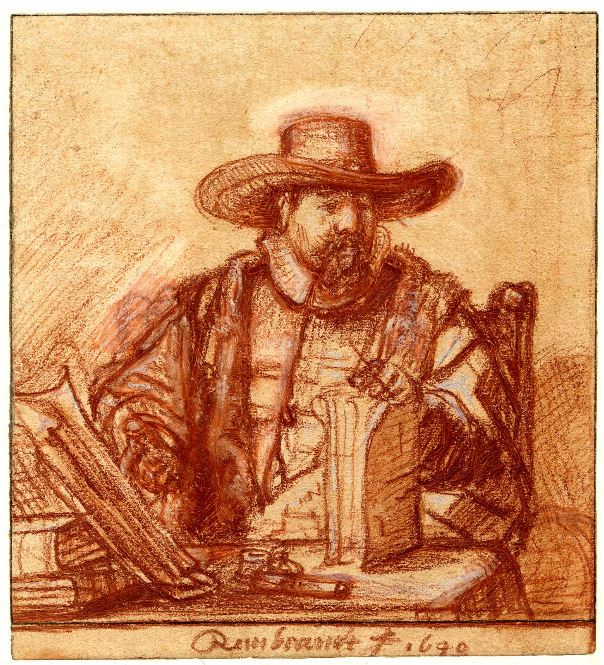

En 1640-1641, Anslo fit appel à Rembrandt pour son portrait. Le prédicateur demanda probablement au peintre de réaliser une esquisse afin de se faire une idée du résultat final. Le prédicateur apparaît sur le premier dessin à la sanguine conservé au British Museum.

QUESTION : Qu’y a-t-il de particulier dans ce dessin ?

PUBLIC : ….

KAREL : Alors qu’il était droitier, il tient sa plume de la main gauche, car le dessin est préparatoire à une gravure. Si l’on transfère l’image telle quelle sur une plaque de cuivre ou de zinc, puis qu’on l’imprime, on obtient une image en miroir. Ainsi, dans la gravure imprimée, Anslo apparaîtra avec une plume dans la main droite, puisque l’effet miroir inverse le sens de l’image. Il faut le prévoir dès le départ.

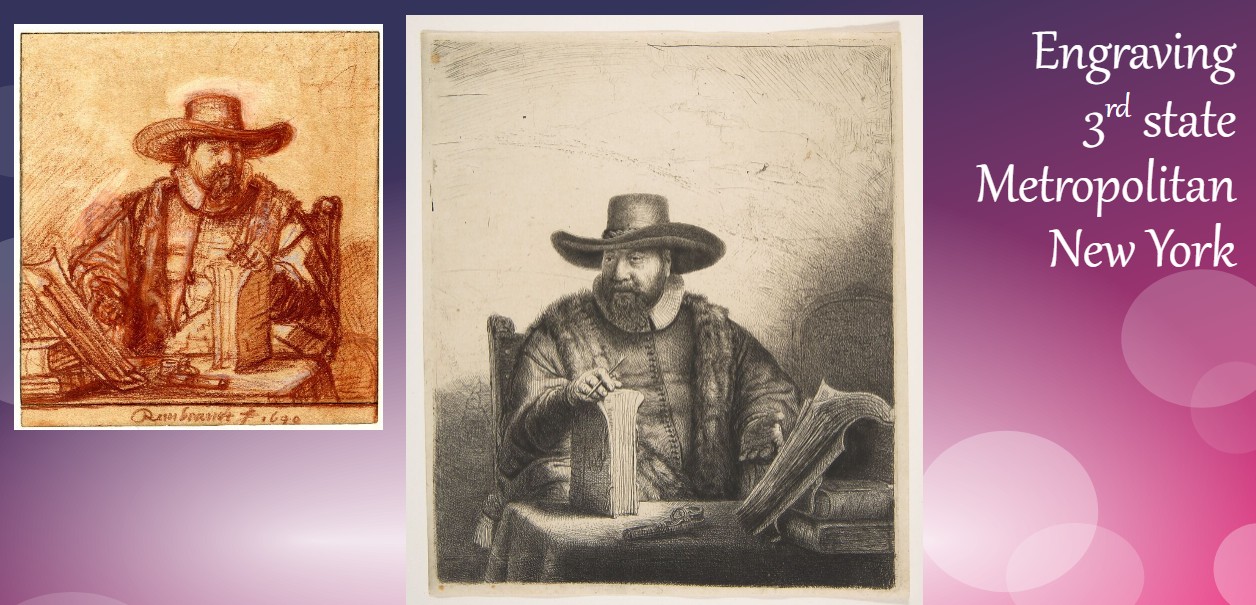

Nous avons ensuite la gravure de 1641, au Metropolitan Museum de New York.

QUESTION : Qu’est-ce qui différencie l’eau-forte du dessin ?

PUBLIC : ….

KAREL : Il a ajouté de l’espace vide. Pourquoi ?

PUBLIC : …

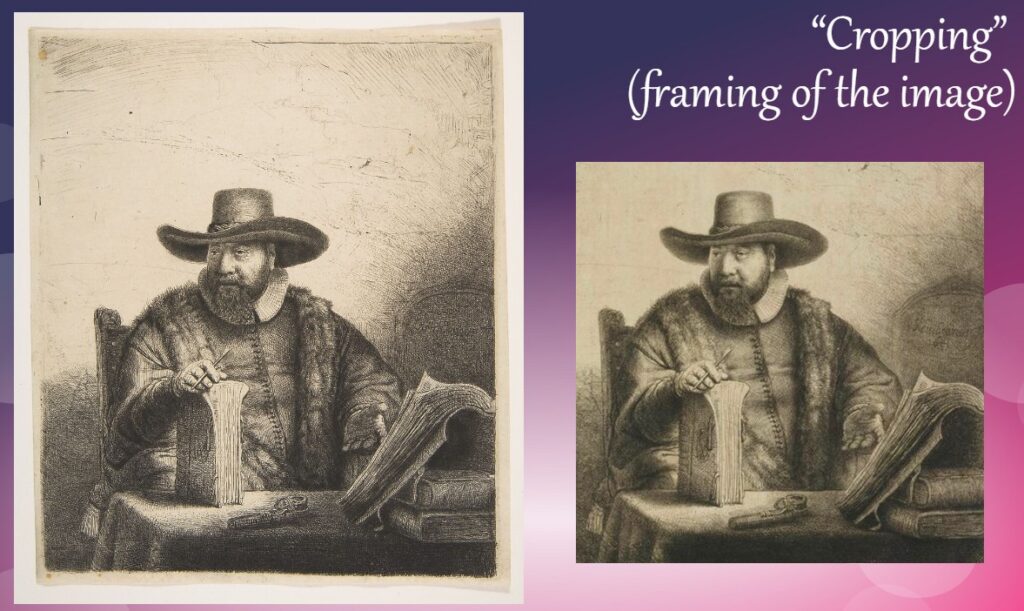

KAREL : Dans une bonne école d’art, on apprend à recadrer l’image.

à gauche, format intégral ; à droite, recadrée Metropolitan Museum, New York.

KAREL : Mais attendez une minute, cet espace supplémentaire est-il vraiment vide ?

PUBLIC : …

KAREL : En fait, il a ajouté deux choses :

- un clou dans le mur derrière lui (très esthétique !)

- un tableau posé au sol, l’image tournée vers le mur (également très esthétique).

Étrange ? Pas tant que ça, puisque la congrégation s’appelait De grote spijker (« Le grand clou », clou signifiant également le « grand magasin » ou la « grange » leur servant de temple).

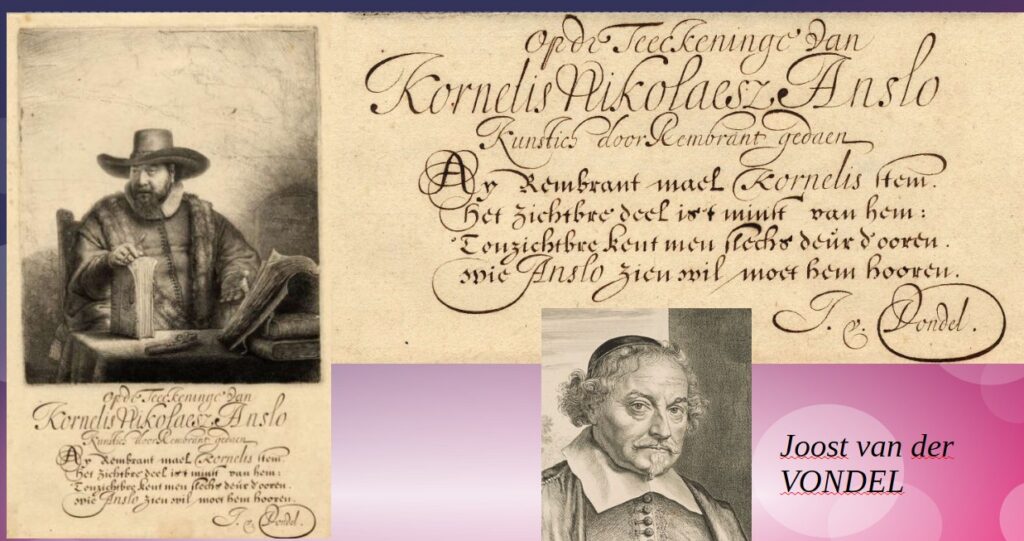

Vondel et la poésie

Pas vraiment. Pour trouver une réponse, il faut faire un petit détour. Ce que l’on sait peu, c’est qu’en dessous des tirages de la gravure apparaît souvent, ajouté à la main, un court poème de Joost van der Vondel, considéré comme le plus grand poète de langue néerlandaise :

On peut y lire en néerlandais/flamand :

“Op de Teekeninge van / Kornelis Nikolaesz Anslo /

Kunstich door Rembrandt gedaen /

Ay Rembrandt mael Kornelis stem /

het zichtbare deel is’t minst van hem /

’t onzichtbare kent men slecht deur d’ooren /

wie Anslo zien wil, moet hem hooren. /

J. v. Vondel »

Traduction française :

« Ô Rembrandt, peins la voix de Cornelis.

La partie visible est la moindre de lui ;

l’invisible, nous ne le connaissons que par nos oreilles ;

celui qui veut voir Anslo doit l’entendre. »

J. v. Vondel

ou, la version rimée que m’a offerte mon amie russe:

« Rembrandt, ô peins, vibrant, la voix de Cornelis.

La part visible de lui n’est qu’une esquisse

Son invisible, c’est l’ouï qui nous le révèle;

Seul qui l’entend puisse voir Anslo tel quel.«

Jusqu’en 1641, Vondel fut le doyen des Waterlanders, le groupe mennonite d’Amsterdam dont Anslo était un prédicateur de premier plan.

Son poème mentionne un « tekening » (dessin) et, en effet, on peut déjà trouver le poème au verso de l’esquisse initiale. On peut penser qu’Anslo a montré, pour avis, l’esquisse préparatoire de Rembrandt à Vondel, le doyen de sa congrégation.

En réagissant par son poème, Vondel met en lumière trois points :

- Il affirme haut et fort la position officielle de la congrégation des mennonites, à savoir que la parole (et plus encore la voix, c’est-à-dire la parole prononcée) est supérieure à l’image pour évangéliser l’humanité. Transformer les autres par sa voix a plus de valeur que le simple apprentissage, et enfin, que pour connaître il faut enseigner.3

- Vondel fait subtilement comprendre que son propre art, la poésie, est supérieur à celui de Rembrandt, la peinture…

- Il dit que Rembrandt pourrait même faire mieux.

Il est clair que Rembrandt s’est senti interpellé par les remarques plutôt amicales du poète. La gravure pourrait constituer une première réponse du peintre, puisqu’elle souligne l’importance de la parole par cette idée du clou, symbolisant l’image décrochée et placée face contre le mur.

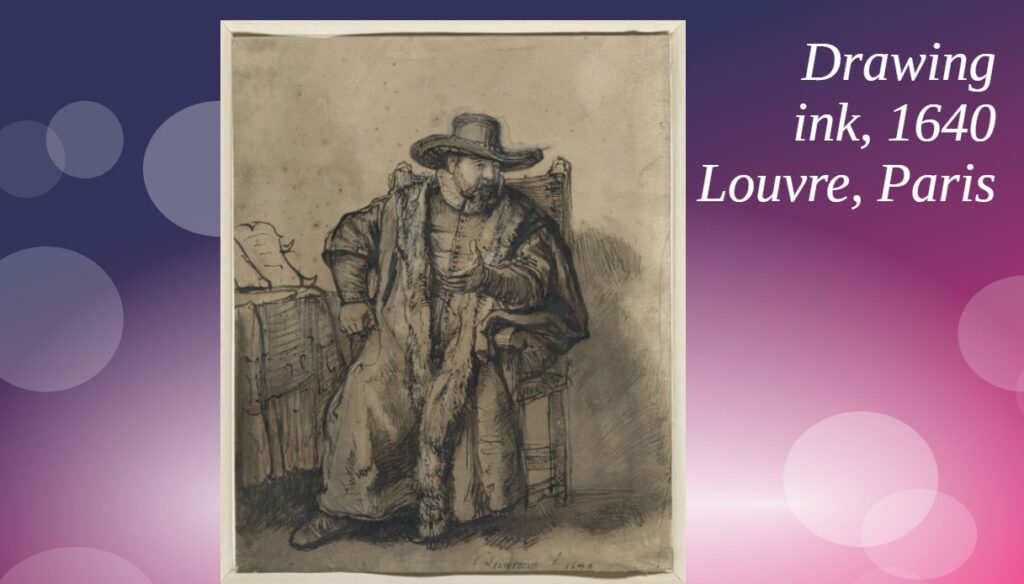

Mais pour préparer le grand tableau à l’huile, Rembrandt réalisa une nouvelle esquisse, aujourd’hui conservée au Louvre.

L’iconographie de la gravure était certainement comprise des mennonites, mais cela ne suffisait pas à toucher un public plus large au fil du temps. Il fallait donc inventer autre chose, visuellement parlant, pour présenter à un niveau supérieur le même argument et surmonter le défi de « peindre l’invisible ».

Déjà dans le dessin du Louvre, la main d’Anslo se déplace vers la gauche, ou plutôt sa tête vers la droite, donnant l’impression que le prédicateur se penche vers son interlocuteur. Dans ce deuxième dessin, si Anslo ne parle pas encore, bien qu’il soit « sur le point » de parler, il se trouve dans une position instable, disons de transition, entre deux mouvements, c’est-à-dire en « point de changement de mouvement » (mid-motion-change, comme l’a formulé Lyndon LaRouche).

La parole sera pleinement manifeste dans le tableau final : la bouche d’Anslo est ouverte et ses sourcils sont levés.

Mais au-delà du simple portrait d’Anslo, Rembrandt ajoute un élément totalement inédit : une personne qui écoute avec une attention extrême.

Ainsi, pour peindre la « voix » (le son), il peint un autre phénomène invisible, son contraire : le silence. Une voix qui résonne sans auditeur est aussi morte qu’un mot dans un livre.

Par là, Rembrandt surmonte le paradoxe de Vondel et affirme la supériorité de son art, la peinture, et le fait que, par l’image, les apparents opposés du son et du silence peuvent être dépassés et rendre visible la parole de Dieu, agissant à travers la voix d’Anslo et surtout l’écoute de sa femme.

Alors, la lumière céleste de Dieu pénètre dans la pièce et éteint la lumière terrestre des bougies pour faire place à la lumière céleste.

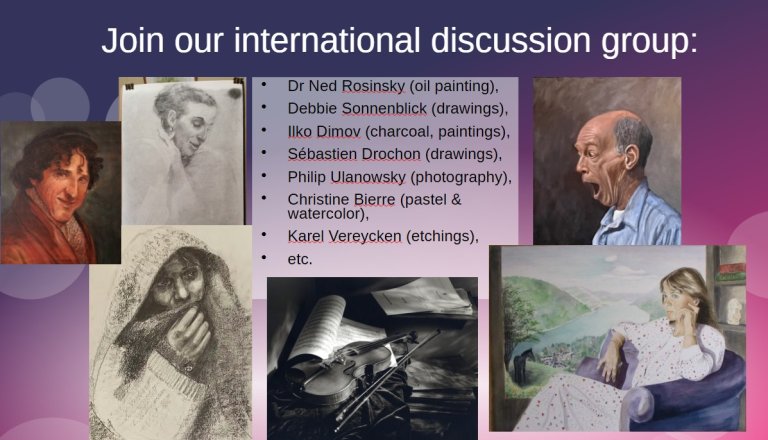

Pour conclure, si vous souhaitez poursuivre ce type de discussion, je vous invite à rejoindre le groupe de travail international sur l’art, parmi les artistes amateurs de notre mouvement. Ce groupe fut lancé par le Dr Ned Rosinsky. À ce jour, il comprend principalement son initiateur, Debbie Sonnenblick, Ilko Dimov, peut-être Sébastien Drochon, Philip Ulanowsky, Christine Bierre et moi-même. Vous pouvez voir quelques-unes de leurs œuvres ici. N’hésitez pas à me contacter à ce sujet.

Merci

BIOGRAPHIE SOMMAIRE :

- Corpus des peintures de Rembrandt, base de données

https://rembrandtdatabase.org/literature/corpus.html - Filippi, Elena, Weisheit zwischen Bild und Word in Fall Rembrandt, Coincidentia, groupe 2/1, 2011

- Haak, Bob, Rembrandt : sa vie, son œuvre et son époque, Thames & Hudson, 1969

- Kauffman, Ivan J., Voir la lumière, Essais sur les images religieuses de Rembrandt, Academia.edu, 2015

- Schama, Simon, Les yeux de Rembrandt, Alfred A. Knopf, 1999

- Schwartz, Gary, Rembrandt, Flammarion, Mercatorfonds, 2006

- Tümpel, Christian, Rembrandt, Albin Michel, Mercatorfonds, 1986

- Vereycken, Karel, Rembrandt, bâtisseur de nation, Nouvelle Solidarité, 1985

- Vereycken, Karel, Rembrandt et la lumière d’Agapè, Artkarel.com, 2001

- Wright, Christopher, Rembrandt, Citadelles et Mazenot, 2000.

- Les experts ont souvent divergé quant à l’identité de la femme. S’agit-il de sa mère, de son épouse ou d’une servante de l’hospice fondé par Anslo ? En 1767, Camelis van der Vliet, la gouvernante de l’hospice, rapporta un passage des archives indiquant qu’Anslo prêchait l’Évangile non seulement en public mais aussi « à sa femme et à ses enfants ; tout comme il est merveilleusement représenté dans le tableau susmentionné, parlant à sa femme de la Bible qui est ouverte devant lui, et que sa femme, représentée d’une manière inimitable et artistique, écoute avec une attention dévote ». A cela s’ajoute que la femme n’est pas vêtue comme une indigente pensionnaire d’un hospice, mais conformément à son statut d’épouse d’un riche marchand. Ce n’est que bien plus tard que le tableau, réalisé pour la demeure privée d’Anslo, deviendra propriété de l’hospice. ↩︎

- En 1686, le critique d’art italien Filippo Baldinucci déclara que « l’artiste professait à cette époque la religion des ménistes (mennonites) ». Des recherches récentes confirment que Rembrandt avait des liens étroits avec la communauté mennonite Waterlander d’Amsterdam, notamment par l’intermédiaire d’Hendrick Uylenburgh, un marchand d’art mennonite qui dirigeait un atelier d’artistes où Rembrandt travailla de 1631 à 1635. Rembrandt devint le peintre en chef de l’atelier et épousa en 1634 la cousine germaine de Van Uylenburgh, Saskia van Uylenburgh, qui n’était pas mennonite. ↩︎

- Le débat sur le rôle exact de la voix, de la parole et de l’image pour les prêcheurs, dégénéra en 1625 en une violente dispute entre les membres de la communauté des Waterlanders d’Amsterdam et d’ailleurs. Une faction affirmait que la parole écrite n’était qu’une voix « morte » et que seul importait la parole vivante, c’est-à-dire Jésus, qui était vivant en chacun en tant que « parole intérieure » des chrétiens. En publiant un pamphlet anonyme, Anslo a pu calmer le débat et réconcilier les croyants, évitant ainsi un schisme. ↩︎

CFA selects Karel Vereycken as « Finalist » Paris Exhibition Contest

The awards and titles in this Paris Exhibition Contest included « Selected Artist », « Finalist », and « Creative Excellence ».

On Nov. 21, 2025, Franco-Belgian painter engraver Karel Vereycken was informed by the New York-based Circle Foundation of the Arts (CFA) that he was NOT among the « Selected Artists » having the honor to have their artworks presented by CFA at the Art3F Art Fair, Paris, 2026.

However, CFA’s director Myrina Tunberg Georgio, wrote to Vereycken:

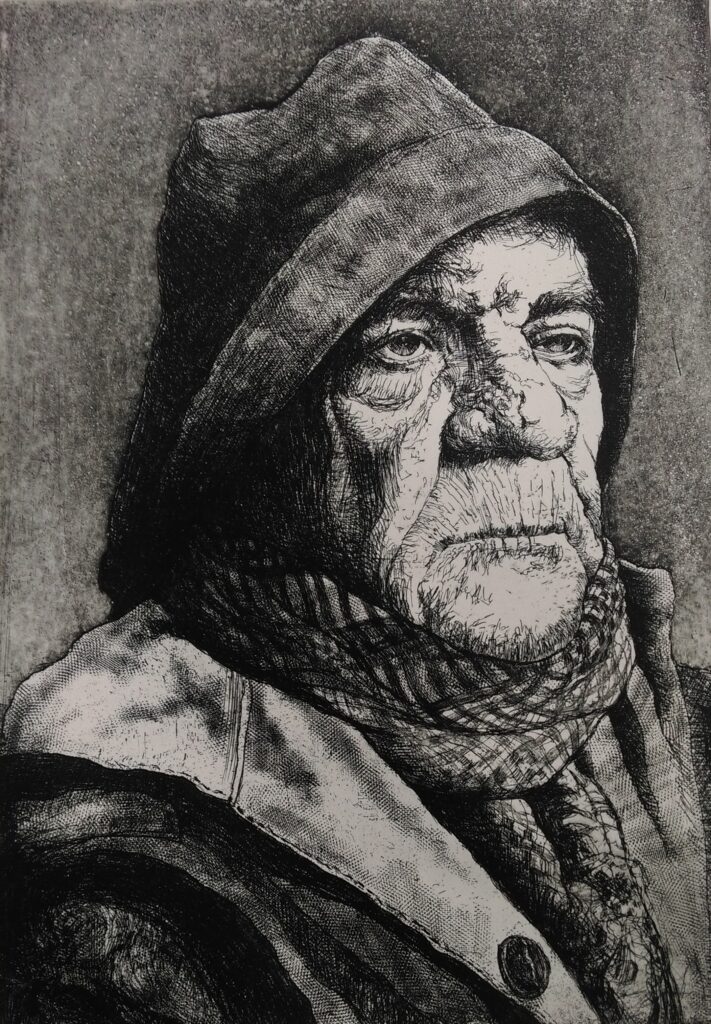

« I am very pleased to let you know that your work « Flemish Fisherman » really stood out me and you are selected as a Contest Finalist. »

Karel Vereycken’s work featured in giant World Art Collection book

Karel Vereycken’s artwork will be included in the « World Art Collection« , an incredible international project by Culturale Lab that brings together more than 5,000 artists from every corner of the globe, creating a monumental publication that celebrates creativity in all its forms.

This is to become the biggest art project book ever created, connecting artists, galleries, and art lovers worldwide. It will appear in the autumn of 2026.

Karel Vereycken’s work selected by Divide Magazine

On November 9, 2025, Karel Vereycken was informed by the leading London-based contemporary Art Magazine Divide :

« We’re excited to let you know that your work has officially been selected and published in Divide Magazine Issue 16! » (p. 91)

« This round was an especially hard decision — we received an incredible number of strong submissions, so making final selections wasn’t easy. That’s why we’re extra thrilled to include your work in this issue. »

You can view and download your free digital copy at: https://issuu.com/divideartmagazine/docs/divide_magazine_-_issue_16

Divide is « an international, independent, bimonthly contemporary art publication based in London, England. It is known for featuring emerging and established visual artists from around the globe, showcasing diverse mediums including photography, mixed media, and installation art. » The magazine is available in print and online versions.

Karel Vereycken awarded in 10th Figurative Art Competition

On Nov. 7, 2025, Karel Vereycken got the following information from the Los Angeles-based global online art gallery and platform for artists TERAVARNA:

« We’re delighted to bring you the exciting news that you have won an award in the « 10th FIGURATIVE » International Juried Art Competition ».

The exhibition of your winning artwork is currently being displayed in TERAVARNA’s winner’s gallery: https://www.teravarna.com/winners-2025-figurative-10.

Le Dos de la Cuillère

Karel Vereycken wins Talent Prize Award for « 13th Open » art contest

On Oct. 21, 2025, painter-engraver Karel Vereycken got the following notification from the Los Angeles-based global online art gallery and platform for artists TERAVARNA:

« We’re delighted to bring you the exciting news that you have won a TALENT PRIZE AWARD in the « 13th OPEN » International Juried Art Competition. »

The exhibition of your winning artwork is currently being displayed in our winner’s gallery: https://www.teravarna.com/winners-2025-open-13«

Karel’s color engraving « Farmers of Sudan », for which the prize was awarded, is currently on display at the exhibition « Estampes d’automne » at the Bo Halbirk engraving workshop in Montreuil where it can be seen till december 12, 2025.

Le Plan Oasis, socle d’un Etat palestinien et source de paix pour la région

Dossier élaboré par Karel Vereycken à partir des propositions et recherches effectuées par les membres et collaborateurs de l’Institut Schiller à l’échelle internationale.

Karel Vereycken selected for the book « 100 Artists of Europe »

Thrilled to announce that I’ve been selected to be featured in the forthcoming book « 100 Artists of Europe », to appear in 2026. Honored to be part of this initiative celebrating creativity across our continent. #100ArtistsOfEurope #EuropeanArt #CultureAndArt

Preview of publication

Karel Vereycken wins « Top in Category Award » for Printmaking

On Oct. 10, 2025, the Circle Foundation for the Arts (CFA) Director Myrina Tunberg Georgiou informed Karel Vereycken he won, with his engraving Farmers of Sudan, the « Top in Category Award » in Printmaking for the 11th International Artist of the Month Contest.

« Your work really stood out to me and you have been selected as Top in Category. It is clear to me that you have a solid vision, your practice is cohesive and the work is aesthetically remarkable » she wrote.

Karel Vereycken wins « 12th ANIMAL » Talent Prize Award

On Oct. 8, 2025, Karel Vereycken got the following information from the Los Angeles-based global online art gallery and platform for artists, TERAVARNA:

« We’re delighted to bring you the exciting news that you have won a TALENT PRIZE AWARD in the « 12th ANIMAL » art competition. [of TERAVARNA]

« The exhibition of your winning artwork is currently being displayed in our winner’s gallery: https://www.teravarna.com/winners-2025-animal-12

The etching for which the prize was awarded will be shown at the upcoming exhibition « Estampes d’automne » in Montreuil, France, opening Oct. 10 till Dec. 12.

On Sunday Oct. 12, Karel VEREYCKEN will do an onsite demonstration of engraving techniques. Hope we can meet there?

Posted by: Karel Vereycken | on décembre 30, 2025

AUDIO: Bruegel’s Mad Meg: we see her madness, but do we see ours ?

More information on Bruegel:

Posted in Audio comments, Comprendre, Etudes Renaissance | Commentaires fermés sur AUDIO: Bruegel’s Mad Meg: we see her madness, but do we see ours ?

Tags: antwerpen, artkarel, audio, comment, dessin, Dulle Griet, Karel, Karel Vereycken, Maagdenhuis, Mayer van den Bergh, peinture